Chinese americans

by L. Ling-chi Wang

Overview

China, or Zhongguo (the Middle Kingdom), the third largest country in the world, occupies a significant portion of southeast Asia. The land mass, 3,657,765 square miles (9,700,000 sq. km.), or as big as all of Europe, is bounded to the north by Russia and Mongolia, to the west by Russia and India, to the southwest by the Himalayas, to the south by Indochina and the South China Sea, and to the east by the Yellow Sea and the Pacific Ocean. Three major rivers flow through China: the Huanghe (Yellow River) in the north; the Yangzi in the heartland; and the Zhujiang (Pearl River) in the south. Eighty-five percent of China's land is nonarable, and the rest is regularly plagued by flood and drought.

Upon this land, China now feeds its 1.3 billion people (1990), one-fifth of humanity. Ninety-four percent are Han Chinese; the remaining six percent are made up of the 55 non-Han minorities, the most prominent of whom are the Zhuang, Hui, Uighur, Yi, Tibetan, Miao, Mongol, Korean, and Yao. These minorities have their own history, religion, language, and culture.

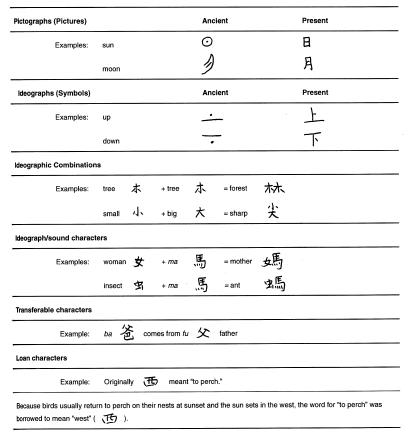

The official language of China is putonghua or Mandarin ( guanhua ), spoken by over 70 percent of the Han Chinese. The remaining Chinese, living mostly in southern China, speak the other seven major Chinese dialects: wu, xiang, gan, northern min, southern min, yue (Cantonese), and kejia (Hakka). In spite of their mutual unintelligibility, all eight branches of Chinese share the same writing system, the only fully developed ancient system of writing still used. The earliest examples of this system of Chinese writing appear on thousands of animal bones and tortoise shells from the middle of the second millennium B.C., during the late Shang Dynasty. However, according to recent archeological evidence, some 32 inscribed symbols on painted pottery from an early Yangshao culture site near Xi'an in Shaanxi, suggest the existence of Chinese writing as early as 6,000 years ago.

HISTORY

Chinese historians have estimated that Chinese civilization began about 5,000 years ago in the Huanghe (Yellow) River basin and the middle Yangzi region. The voluminous history, Shi Ji ("Historical Records"), by Sima Qian (b. 145 B.C.) and recent archeological finds support the validity of the assumption. For example, the neolithic sites of the Yangshao culture along the midsection of the Yellow River confirm the traditional view that the river basin was the cradle of the Chinese civilization.

Legends have it that Huangdi ("the Yellow Emperor") defeated his rival tribes, established the first Chinese kingdom, made himself tienzi, or "The Son of Heaven," and invented many things for the benefit of his people, including clothing, boats, carts, medicine, the compass, and writing. Following Huangdi, historians believe that the Xia Dynasty (2100-1600 B.C.) was the first dynasty of China and marked the beginning of Chinese history. Xia, weakened by corruption in its final decades, was eventually conquered by a Shang king to the east who established the Shang Dynasty (1600-1100 B.C.). The Shang achievements can be readily seen from the remnants of its spectacular palaces, well-crafted giant bronze cauldrons, refined jade carvings, and massive written records. During the Zhou Dynasty (1100–771 B.C.), the Chinese idea of the emperor, being the "Son of Heaven" who derived his mandate from heaven, was firmly established. In the highly organized feudal society, the Zhou royal family ruled over hundreds of feudal states.

Beginning in 770 B.C., Chinese history entered two periods of turmoil and war: the Spring/Autumn (770-476 B.C.) and the Warring States (475-221 B.C.). During these 550 years, the former feudal states engaged in perpetual wars and brutal conquests. During the same time, China witnessed unprecedented progress in agriculture, science, and technology and reached the golden age of Chinese philosophy and literature. Confucius (551-479 B.C.), founder of Confucianism; Laozi (sixth century), the founder of Daoism; the egalitarian Mozi (480-420 B.C.); and Han-fei (280-233 B.C.), founder of legalism, defined the character of Chinese civilization and made profound and enduring contributions to the intellectual history of the world.

Qin Shi Huangdi of the Qin state finally crushed all the rival states and emerged as the sole ruler of the Chinese empire in 221 B.C. Qin extended the borders of China; imposed harsh laws; completed the Great Wall; built a transportation network; and standardized weights, measures, currency, and, most importantly, the Chinese writing system. The brutality of his rule soon led to widespread rebellion, and the Qin rule was eventually replaced by the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.). The Han emperor firmly established the Chinese state under Confucianism and created an educational and civil service system that remained in use until 1911. During this period, China came into contact with the Roman Empire and with India.

During the Sui-Tang era, China traded extensively by land and by sea with the known world, and Islam, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity were brought into China. But Tang began to decline toward the end of the eighth century, causing rebellions of warlords from within and invasions from without. After Tang, China was again divided. In 1211 Genghis Khan, a Mongolian leader, began the invasion into China from the north, but the conquest was not completed until 1279 under Kublai Khan, his grandson, who established the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in China. During Mongolian rule, China traded extensively with Europe, and Marco Polo brought China's achievements to European attention.

The decline of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) led to the conquest of China for the second time by a foreign power, the Manchu, from the northeast. The Manchu established the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and again expanded China's borders. Like the Mongols, however, the Manchu conquerors were also conquered and absorbed by the Chinese. Failed reform within the Quing administration, internal pressure through various organized rebellions, external pressure from the major Western powers, and the military defeat by Japan in 1895 all led China to become increasingly isolated and weak.

MODERN ERA

The isolation was finally broken when the British defeated China in the Opium War (1839-1842), forcing China to open its ports to international trade and exposing China in the next 100 years to Western domination. Under the yoke of imperialism and mounting political corruption and internal unrest, especially the Taiping Uprising, the Qing Dynasty collapsed in a revolution led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen in 1911.

The new Republic of China, under the leadership of Sun, his dictatorial successor Chiang Kaishek, and the Nationalist party (Guomindang or Kuomintang), proved both weak and corrupt. From the invasion by Japan, which began in 1931, to a strong insurgent movement led by Communist Mao Tse-tung, the Chiang regime was severely undermined and eventually ousted from China in 1949, retreating to Taiwan under U.S. military protection. Mao established the People's Republic of China, free from foreign domination for the first time since the Opium War. His alliance with the Soviet Union in the 1950s, however, led to its isolation throughout the Cold War. His support of the wars in Korea and Vietnam made China the enemy of the United States. The United States-China detente was initiated in the historic meeting between President Richard Nixon and Mao Tsetung and Chou Enlai in 1972. In 1978, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China also undertook a series of bold economic reforms. In 1979 the United States broke ties with Taiwan and normalized its relations with China. Since the end of the Cold War, China has become a major political and economic power in an increasingly economically integrated, yet disorderly world.

During the war in Yugoslavia in 1999, relations between China and the United States became strained. On May 7, 1999, in what Secretary of Defense Harold Brown called a "stupid" mistake, a U.S. war plane bombed the Chinese Embassy, killing two persons and injuring several others. The United States explained that it had used an old map to find its targets, but Chinese Foreign Minister Tan Jiaxuan called the explanation "unconvincing" and questioned whether it was a mistake.

HISTORY OF CHINESE IMMIGRATION

In many respects, the motivations for Chinese to go to the United States are similar to those of most immigrants; some came to "the Gold Mountain" ( Jinshan in Mandarin or Gumsaan in Cantonese), the United States, to seek better economic opportunity, while others were compelled to leave China either as contract laborers or refugees. They brought with them their language, culture, social institutions, and customs, and over time, they made lasting contributions to their adopted country and tried to become an integral part of the U.S. population.

However, their collective experience as a racial minority, since they first arrived in the mid-nineteenth century, differs significantly from the European immigrant groups and other racial minorities. Chinese were singled out for discrimination through laws enacted by states in which they had settled; they were the first immigrant group to be targeted for exclusion and denial of citizenship by the U.S. Congress in 1882. Their encounter with Euro-Americans has been shaped not just by their cultural roots and self-perceptions but also by the changing bilateral relations between the United States and China. The steady infusion of immigrants from China and Taiwan and easy access to traditional and popular cultures from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, through telecommunication and trans-Pacific travel, have helped create a new Chinese America that is as diverse as it is fast-changing. Chinese American influence in politics, culture, and science, is felt as much in the United States as it is in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

The movement of the Chinese population within China (called the han, or tang, people in pre-twentieth century China and huaqiao, or huaren, in the twentieth century), has continued throughout the 5,000-year history of China. Huaqiao (literally, sojourning Chinese), or more accurately, huaren (persons of Chinese descent), is a term commonly used for Chinese residing outside of China proper or overseas. Today, about 35 million Chinese live outside of China in over 130 countries. Chinese immigration to the United States is part of this great historic process.

Even though ancient Chinese legends and writings, most notably the fifth-century account by Weishen of a land called Fusang, suggest the presence of Chinese in North America centuries before Christopher Columbus, and a few Chinese were reported to be among the settlers in the colonies in the east coast in the eighteenth century, significant Chinese immigration to the West Coast of the United States ( Jinshan ) did not begin until the California Gold Rush.

Chinese immigration can be roughly divided into three periods: 1849-1882, 1882-1965, and 1965 to the present. The first period, also known as the first wave, began shortly after the Gold Rush in California and ended abruptly with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first race-based immigration law. During this period, the Chinese could act like other pioneers of the West and were allowed to immigrate or travel freely between China and San Francisco. Thousands of Chinese, mostly young male peasants, left their villages in the rural counties around the Zhujiang, or Pearl River, delta in Guangdong Province in southern China to become contract laborers in the American West. They were recruited to extract metals and minerals, construct a vast railroad network, reclaim swamp-lands, build irrigation systems, work as migrant agricultural laborers, develop the fishing industry, and operate highly competitive, labor-intensive manufacturing industries in the western states. The term limit of their contracts, together with the strong anti-Chinese sentiment that greeted them upon their arrival, precluded most of them from becoming permanent settlers. Under these circumstances, most of the laborers had only limited objectives: to advance their own and their families' economic well-being during their sojourn and to return to their ancestral villages to enjoy the fruits of their labor during retirement. At the end of the first period, the Chinese population in the United States was about 110,000, or one-fifth of one percent, of the U.S. total.

When Chinese labor was no longer needed and political agitation against the Chinese intensified, the U.S. Congress enacted a series of very harsh anti-Chinese laws, beginning in 1882, designed to exclude Chinese immigrants and deny naturalization and democratic rights to those already in the United States. Throughout most of the second period (the period of exclusion; 1882-1965), only diplomats, merchants, and students and their dependents were allowed to travel between the United States and China. Occasional loopholes in the late 1940s and 1950s, created by special legislation for 105 Chinese immigrants per year in 1943, the presence of Chinese American war brides in 1946, and selected refugees in 1953 and 1961, allowed some Chinese to enter. Otherwise, throughout this period, Chinese Americans were confined largely to segregated ghettos, called Chinatowns, in major cities and isolated pockets in rural areas across the country. Deprived of their democratic rights, they made extensive use of the courts and diplomatic channels to defend themselves, but with limited success.

The Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, particularly the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, finally ushered in a new era, the third period in Chinese American immigration history. Chinese Americans were liberated from a structure of racial oppression. The former legislation restored many of the basic rights denied Chinese Americans, while the latter abolished the racist law that severely restricted Chinese immigration and prevented Chinese Americans from being reunited with their loved ones. Under these new laws, thousands of Chinese came to the United States each year to reunite with their families and young Chinese Americans mobilized to demand racial equality and social justice.

Equally significant are two other types of Chinese immigrants who have been entering the United States since the early 1970s. The first type consists of highly select and well-educated Chinese. No less than 250,000 Chinese intellectuals, scientists, and engineers have come to the United States for advanced degrees. Most of them have stayed to contribute to U.S. preeminence in science and technology. The second type is made up of tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants who have entered the United States to escape either political instability or repression throughout East and Southeast Asia, the result of a dramatic reversal of the U.S. Cold War policies toward China in 1972 and toward Vietnam in 1975. Some of these are Chinese from the upper and middle classes of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and throughout Southeast Asia who want long-term security for themselves, their businesses, and their children. Others are ethnic Chinese from Vietnam and Cambodia who became impoverished refugees and "boat people," when Vietnam implemented its anti-Chinese or "ethnic cleansing" policies in 1978. It was this steady infusion of Chinese immigrants that accounted for the substantial increase of the Chinese American population, amounting to 1.6 million in the 1990 census, making them the largest Asian American group in the United States.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Economic development and racial exclusion defined the patterns of Chinese American settlement. Before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the patterns of Chinese settlement followed the patterns of economic development of the western states. Since mining and railway construction dominated the western economy, Chinese immigrants settled mostly in California and states west of the Rocky Mountains. As these industries declined and anti-Chinese agitation intensified, the Chinese retreated—and sometimes were forced by mainstream society—into small import-export businesses and labor-intensive manufacturing (garments, wool, cigars, and shoes) and service industries (laundry, domestic work, and restaurants) in such rising cities as San Francisco, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Seattle; into agriculture in rural communities in California; and into small retail business in black rural communities in the Deep South. Some Chinese found themselves systematically evicted from jobs, land, and businesses and their rights, privileges, and sanctuaries in mainstream society permanently suspended. By the early twentieth century, over 80 percent of the Chinese population were found in Chinatowns in major cities in the United States.

Chinatowns remained isolated and ignored by the American mainstream until after World War II. After the war, as the United States became a racially more open and tolerant society, emigration from the Chinatowns began. With new employment opportunities, a steady stream of Chinese Americans moved into new neighborhoods in cities and into sprawling suburbs, built around the rising military-industrial complex during the Cold War. As the new waves of postwar immigrants arrived, the poor moved into historic Chinatowns and the more affluent settled into new neighborhoods and suburbs, creating the so-called new Chinatowns in

Gim Chang, a Chinese resident of San Francisco, cited in Ellis Island: An Illustrated History of the Immigrant Experience, edited by Ivan Chermayeff et al. (New York: Macmillan, 1991)."I myself rarely left Chinatown, only when I had to buy American things downtown. The area around Union Square was a dangerous place for us, you see, especially at nighttime before the quake [1906]. Chinese were often attacked by thugs there and all of us had to have a police whistle with us all the time."

cities including San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Houston, and a string of suburbs with strong Chinese American presence, such as the ones along Interstate 10 west of Los Angeles and Highway 101 between San Francisco and San Jose. The new immigrants brought new cultural and economic vitality into both the new and the old communities even as they actively interacted with their Euro-American counterparts.

From interactions under ghetto confinement, to the rise of a suburban Chinese American middle class, to the revitalization of historic Chinatowns, Chinese American communities across the United States have become more diverse, dynamic, and divided, with the arrival of new waves of immigrants creating new conflicts as well as opportunities that are uniquely Chinese American.

The growth and proliferation of the Chinese American population in the last three decades also aroused resentment and hostility in cities and suburbs and in the spheres of education and employment. For example, some neighborhoods and suburbs, most notably, San Francisco and Monterey Park, California tried to curb Chinese American population growth and business expansion by restrictive zoning. Chinese American achievements in education, seen with increasing apprehension in some cases, has led to the use of discriminatory means to slow down or reverse their enrollment in select schools and colleges. Since the early 1980s, there has been a steady increase in incidents of racial violence reported. These trends have been viewed with increasing alarm by Chinese Americans across the United States.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries, Chinatown was a permanent home for the Chinese who were cut off from China "like orphans" ( haiwai guer ) and yet disenfranchised from the Euro-American mainstream. Assimilation was never a viable choice for Chinese Americans, who were excluded and denied citizenship because they were deemed nonassimilable by the white mainstream.

In 1852 Governor John Bigler of California, demanded Chinese exclusion on the grounds that they were nonassimilable. In 1854 the California Supreme Court, in Hall v. People, ruled that Chinese testimony against whites was inadmissible in a court of law because, "the same rule which would admit them to testify, would admit them to all the equal rights of citizenship; and we might soon see them at the polls, in the jury box, upon the bench, and in our legislative halls." By congressional statutes and judicial decisions, Chinese immigrants were made ineligible for naturalization, rendering them politically disenfranchised in a so-called democracy and exposing them to frequent and flagrant violations of their constitutional rights.

Chinese Americans could not understand how the United States could use gunboat diplomacy to open the door of China and at the same time use democracy to close the door to Chinese Americans. The bitter encounter with American democracy and hypocrisy planted a seed of modern Chinese nationalism, which led the Chinese Americans to fight for equal rights at home and to orient their collective will toward freeing China from imperialist domination. They linked the racial oppression of the Chinese in the United States to the impotence of China.

Life within the Chinatown ghetto, therefore, was hard but not stagnant. Legally discriminated against and politically disenfranchised, Chinese Americans established their roots in Chinatowns, fought racism through aggressive litigation and diplomatic channels, and participated actively in various economic development projects and political movements to modernize China. For the immigrant generation, there was only one choice, modernization for themselves and for China. Assimilation was seen as an impossibility. For the American-born generation, many members of which made a concerted effort to assimilate, mainstream society remained inhospitable.

In the nineteenth century, most Chinese immigrants saw no future in the United States and oriented their lives toward eventual return to China, luoye-guigen, translated it means "fallen leaves return to their roots." With this sojourner mentality, they developed a high degree of tolerance for hardship and racial discrimination and maintained a frugal Chinese lifestyle, which included living modestly; observing Chinese customs and festivals through family and district associations; sending regular remittance to parents, wives, and children, and maintaining village ancestral halls and charities. Parents tried to instill Chinese language and culture in their children, send them to Chinese schools in the community or in China, motivate them to excel in American education, and above all, arrange marriages. The parents in Louis Chu's Eat a Bowl of Tea (1961) tried to find their sons brides in villages in the Zhujiang delta. For the most part, their sole aspiration was to work hard and save enough to retire in comfort back in the villages from which they came.

They also joined social organizations. District associations ( huiguan ) and family associations ( gongsuo ), respectively, represented the collective interest and well-being of persons from the same villages or counties and persons with the same family names. These ascriptive organizations provided aid and comfort to their members, arbitrated disputes, helped find jobs and housing, established schools and temples, and sponsored social and cultural events. Most of these organizations had branches in different Chinatowns, enabling members to travel from one city to another. Together, these organizations formed the Consolidated Chinese Benevolent Association in each city, a de facto ghetto government, to settle disputes among individuals and organizations and to represent the community's interests with both U.S. and Chinese governments, at times through civil disobedience, passive resistance, and litigation, and at other times through diplomatic channels and grassroots protests instigated in China. Their activities brought mixed blessings to the community. At times, these organizations became too powerful and oppressive, and they also obstructed social and political progress. Without question, they left an enduring legacy in Chinese America.

Into these uniquely American ghettos also came a string of Protestant and Catholic missionaries, establishing churches and schools and trying to convert and assimilate the Chinese, as well as a steady stream of political factions and reformers from China, advancing their agendas for modernizing China and recruiting Chinese Americans to support and work for their causes. Both were agents of change, but they worked on different constituencies and at cross purposes: one tried to assimilate them, while the other tried to instill in them a cultural and political loyalty to China.

Virtually all major Christian churches established missions and schools in San Francisco's Chinatown, the largest in the United States and the center of cultural, economic, and political life of Chinese in North America. Among the most enduring institutions were the YMCA and YWCA, the St. Mary's Chinese Mission School, and the Cameron House, a Presbyterian home for "rescued" Chinese prostitutes. The churches, in general, were more successful in winning converts among the American-born generation.

Proportionally smaller in number, those Chinese Americans who were exposed to a segregated but American education very quickly became aware of their inferior status. Many became ashamed of their appearance, status, and culture. Self-hatred and the need to be accepted by white society became their primary obsession. In practice this meant the rejection of their cultural and linguistic heritage and the pursuit of thoroughgoing Americanization: adoption of American values, personality traits, and social behaviors and conversion to Christianity.

Denying their racial and cultural identity failed to gain them social acceptance in the period before World War II. Most found themselves still shut out of the mainstream and were prevented from competing for jobs, even if they were well qualified. Some were compelled to choose between staying in the United States as second-class citizens and going to China, a country whose language and culture had, ironically, become alien to them on account of their attempted assimilation.

For the immigrant generation, there was only one choice: staking their future in China. China's modernization occupied their attention and energy because they attributed their inferior status in the United States to the impotence of China as a nation under Western domination. Reformers from opposing camps in China invariably found an eager audience and generous supporters among the Chinese in the United States. Among the political reformers who frequented Chinatowns across the United States to raise funds and recruit supporters were Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao, and Sun Yat-sen before the 1911 Revolution. During the Sino-Japanese War (1937-41), several leaders of the ruling Kuomintang also toured the United States to mobilize Chinese American support; among them were General Cai Tingkai and Madame Chiang Kai-shek. The factional dispute between the pro-China and pro-Taiwan forces is very much a part of this political legacy. In essence, China's political factionalism became an integral part of Chinese American life.

Between efforts of the missionaries and political reformers, many churches and political parties were established and sectarian schools and newspapers founded. Schools and newspapers became some of the most influential and enduring institutions in Chinese America. Together they played an important role in perpetuating the Chinese culture among the Chinese and in introducing Chinese to ideas of modernity and nationalism.

CUISINE

Chinese tea was a popular beverage in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America. Since the 1960s, Chinese cuisine has been an integral part of the American diet as well. Chinese restaurants are found in small towns and large cities across the United States. Key ingredients for preparing authentic Chinese dishes are now found in all chain supermarkets, and lessons in Chinese cooking are regular features on national television. Chinese take-outs, catering, and chain restaurants have become commonplace in major cities, and Chinese dim sum, salads, and pastas can be found in cocktail lounges and exclusive clubs and resorts. Gone are such pre-1960 dishes as chop suey, chow mien, egg fooyung, and barbecue spareribs. In fact, many Americans have mastered the use of chopsticks and acquired the taste for sophisticated Chinese regional cuisines, such as Cantonese, Kejia (Hakka), Sichuan (Szechuan), Shangdong, Hunan, Mandarin (Beijing), Taiwan (Minnan), Chaozhou (Teo-Chiu), and Shanghai. American households now routinely use Chinese ingredients, like soy sauce, ginger, and hoisin sauce in their food; employ Chinese cooking techniques, such as stir frying; and include Chinese cooking utensils, like the wok and the cleaver, in their kitchens.

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES

Very few Chinese Americans now wear traditional Chinese clothing. On special occasions, some traditional costumes are worn. For example, on the wedding day, a bride might wear a Western wedding gown for the wedding ceremony and then change into a traditional Chinese wedding gown, called gua, for the tea ceremony and banquet. In some traditional families, the elders sometimes wear traditional Chinese formal clothes to greet guests on Chinese New Year's Day. Sometimes, young Chinese American women wear the tightly fitted cengsam ( chongsam ), or qipao, for formal parties or banquets. Occasionally, Chinese styles find their way into American high fashion and Hollywood movies.

DANCES AND SONGS

Chinese opera and folk songs are performed and sung in the Chinese American community. Cantonese opera, once very popular in Chinatown, is performed for older audiences, and small opera singing clubs are found in major Chinatowns in North America. Rarer is the performance of Peking opera. Among the well-educated Chinese, concerts featuring Chinese folk and art songs are well attended and amateur groups singing this type of music can be found in most cities with significant Chinese American populations. Similarly, both classical and folk dances continue to find some following among Chinese Americans. The Chinese Folk Dance Association of San Francisco is one of several groups that promotes this activity. Most American-born Chinese and younger new immigrants, however, prefer either American popular music or Cantonese and Mandarin popular music from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

HOLIDAYS

Most Chinese Americans today observe the major holidays of the Chinese lunar calendar ( yin li ). Today, Chinese calendars routinely provide both the solar ( yang li ) and lunar calendars, and Chinese daily newspapers provide both kinds of dates. The most important holiday is the Chinese New Year or the Spring Festival ( chun jie ), which is also a school holiday in San Francisco.

Family members get together for special feasts and celebrations. The Feast of the Dead ( qing ming or sao mu ), the fifteenth day of the third lunar month, is devoted to tidying tombs and worshiping ancestors. The Dragon-boat Festival ( duan wu or duan yang ), on the fifteenth day of the fifth lunar month, commemorates the death of renown poet, Qu Yuan, who threw himself into the River Milu Jiang in 277 B.C. Usually a dragon-boat race is held

The founding of the People's Republic of China ( guo qing jie ), October 1, 1949 of the solar calendar, is observed by Chinese Americans with banquets and cultural performances in major cities in the United States. Likewise, the founding of the republic by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, October 10, 1911, is commemorated each year in Chinatowns by groups closely associated with the Nationalist government in Taiwan. Not as widely observed are the Children's Day ( er tong jie ) on June 1, Woman's Day ( fu nu jie ) on March 8, and May Day ( lao dong jie ) on May 1.

HEALTH ISSUES

Prewar housing and job discrimination forced the Chinese to live within American ghettos. Discrimination also denied Chinese Americans access to health care and other services. Most relied on traditional Chinese herbal medicine, and the community had to found its own Western hospital, Chinese Hospital, in the early twentieth century. By the time the postwar immigrants arrived in large numbers in the 1960s, Chinatown was bursting at the seams, burdened with seemingly intractable health and mental health problems.

Chinatowns in San Francisco and New York are among the most densely populated areas in the United States. Housing has always been substandard and overcrowded. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Chinatown in San Francisco had the dubious distinction of having the highest tuberculosis and suicide rates in the Unites States. High unemployment and underemployment rates exposed thousands of new immigrants to severe exploitation in sweatshops and restaurants. School drop-outs, juvenile delinquency, and gang wars were symptoms of underlying social pathology.

However, it is wrong to assume that health and mental health problems exist only in the Chinatown ghettos. The overwhelming majority of Chinese Americans no longer live in historic Chinatowns, as mentioned above. While many of the health and mental health-related problems in Chinatown are class-based, many others, such as the language barrier,

Language

Most prewar Chinese arrived in the United States knowing only the various dialects of Cantonese ( Yue ), one of the major branches of Chinese spoken in the Zhujiang delta. The maintenance of Chinese has been carried out by a strong network of community language schools and Chinese-language newspapers. However, with the arrival of new immigrants from other parts of China and the world after World War II, virtually all major Chinese dialects were brought to America. Most prominent among these are Cantonese, Putonghua, Minnan, Chaozhou, Shanghai, and Kejia. Fortunately, one common written Chinese helps communication across dialects.

Today, Chinese is maintained through homes, community language schools, newspapers, radio, and television, and increasingly, through foreign language classes at mainstream schools and universities. The rapid increase of immigrant students since 1965 also gave rise to growing demand for equality of educational opportunity in the form of bilingual education, a demand that resulted in a 1974 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lau vs. Nichols, a case brought by Chinese American parents in San Francisco. Hand in hand with this trend is the teaching of Mandarin or Putonghua, China's national spoken language, in public and community schools.

GREETINGS AND OTHER POPULAR EXPRESSIONS

Cantonese greetings and other popular expressions include: Nei hou ma? (How are you?); Hou loi mou gin (Long time no see); Seg zo fan mei? (Have you eaten?); Zoi gin (Good-bye); Zou tao (Good night); Deg han loi co (Let's get together again); Do ze (Thank you); M'sai hag hei (Don't mention it); Gung hei (Congratulations); and Gung hei Fad coi (Have a prosperous New Year). Mandarin greetings and other popular expressions include: Ni hao (How do you do); Xiexie (Thank you); Bu yong xie or Bu yong keqi (Don't mention it); Dui bu qi (Excuse me); Mei guanxi (It's Okay); and Zaijian (Good-bye).

Family and Community Dynamics

Since most Chinese before 1882 came as contract laborers to perform specific tasks, the Chinese population in the United States in the nineteenth century was predominantly young males, either not yet married or married with their wives and children left in the villages in southern China. According to the 1890 census, there were 107,488 Chinese in the United States. Of these 103,620, or 96.4 percent, were males and only 3,868, or 3.6 percent, were females. Among the male population, 26.1 percent were married, 69 percent single, and 4.9 percent were either widowed or divorced. The male-female ratio was not balanced until 1970.

This uneven sex distribution gave rise to an image of Chinatown as a bachelor society, vividly captured in the pictures taken by Arnold Genthe in San Francisco before the 1905 earthquake and in the description by Liang Qichao during his 1903 travel to the United States. Normal family life for most Chinese Americans did not begin until after World War II, when several thousand war brides were brought in by Chinese American GIs.

The exclusion and anti-miscegenation laws forced most Chinese in the United States to maintain their families across the Pacific. Only the privileged merchant class was able to bring over their wives and children. Under such circumstances, the Chinese population in the United States declined steadily, dipping as low as 61,639 in 1920, before it started to rise again. The Chinese American population therefore had to wait until after World War II for the emergence of an American-born political leadership.

The abnormal conditions also contributed to widespread prostitution, gambling, and opium smoking, most of which were overseen by secret societies, known as tongs, often with the consent of both the Chinatown establishment and corrupt local law-enforcement agencies. The struggle for control of these illicit businesses also gave rise to frequent intrigues, violence, and political corruption and to sensational press coverage of the socalled tong wars.

It was not until the second decade of the twentieth century that a significant, but still proportionally small, American-born generation began to emerge. According to the 1920 census, only 30 percent of Chinese in America were born in the United States, and therefore, American citizens. The ratio of American born to foreign born was finally reversed in 1960, only to be reversed again in 1970 with the massive influx of new immigrants. Unlike the prewar immigrants, the new immigrants came to the United States with their families, and they came to stay permanently.

Today, most middle-class Chinese Americans place the highest priority on raising and maintaining the family: providing for the immediate members of the family (grandparents, parents, and children), acquiring an adequate and secure home for the family, and investing comparatively greater amounts of time and annual income in their children's education. Even among the poorer families, which have neither financial security nor decent housing, keeping the family intact and close and doing all they can to support their children are also priorities. This is why Chinese Americans continue to perform well in education across all income levels, even if the success rates among the poor are less impressive than those among the better off. Across the nation, Chinese American educational achievement is well known. In particular, Chinese Americans are disproportionally represented among the top research universities and the elite small liberal colleges. In graduate and professional schools, they are overrepresented in certain areas, but under-represented in others. In addition to Chinese American students, there are thousands of Chinese foreign students from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

However, it is wrong to assume that all Chinese Americans are living in happy, intact, successful families and raising obedient, motivated, and college-bound children. Traditional Chinese concepts of family and child-rearing, for both the rich and poor, have undergone drastic changes in America due to job status, income levels, living arrangements, and neighborhood conditions, as well as the social and cultural environment of the United States. Chinese Americans face their share of family break-ups, domestic violence, school drop-outs, drug addiction, gang activities, etc.

INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER ETHNIC GROUPS

Racism and past policies of racial segregation have kept Chinese Americans largely separated from the mainstream of the society. Nevertheless, there has been contact between Chinese and other racial groups. For example, some Chinese established small general stores in poor black communities in the rural areas along the Mississippi valley after the Civil War. White missionaries and prostitutes found nineteenth-century Chinatowns to be productive places to carry out their business. Some Chinese laborers married American Indian and Mexican women during the period of exclusion, in spite of anti-miscegenation laws in virtually every state.

Since the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, intermarriage has become more common as U.S. society becomes more open and Chinese Americans more affluent. However, racial prejudice and traditional racist stereotypes persist, contributing to racial distrust and conflict between Chinese Americans and whites, as well as between Chinese Americans and African Americans. For example, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a large number of Chinese American parents in San Francisco mobilized to oppose court-ordered school integration. Chinese American engineer Vincent Chin was brutally murdered in Detroit in 1982 by two unemployed white auto workers because he was assumed to be Japanese and somehow responsible for their loss of jobs. Chinese American Jim Loo of Raleigh, North Carolina, was killed in 1989 by a white person because he was presumed to be a Vietnamese responsible for American deaths in Vietnam.

Religion

All kinds of religions are practiced in the Chinese American community today. There are Christians as well as Buddhists, Daoists, and Confucianists. Chinese churches and temples ( miao ) are found wherever there are Chinese Americans. Most of the old temples are found in historic Chinatowns. For example, in San Francisco's Chinatown in 1892, no fewer than 15 temples were present. Some of the temples were dedicated to the Goddess of Heaven ( Tienhou )—also the god of seamen, fishermen, travelers, and wanderers—while others to Emperor Guangong ( Guandi ), a warrior god. Modern temples, such as the one in Hacienda Heights, California, were built by more recent Chinese immigrants from Taiwan. Likewise, Christian churches, organized by dialects, are found in old Chinatowns as well as in the suburbs.

The majority of Chinese Americans could be characterized as irreligious by Western standards of religion. This does not mean, however, that most of them are devoid of any religious feeling or that they do not practice any religion at all. The majority, in fact, practice some form of Buddhism or Daoism, folk religions, and ancestral worship.

Generally speaking, Chinese are pragmatic in their approach to life and religion. They are somewhat superstitious: they believe in the doctrines of fengsui, which are intended to help in the organization of a home, and they do not want to do anything they personally think is likely to offend the gods or the ways of nature. Toward this end, they choose who they want to worship and they worship them through certain objects or locations in nature. They also worship through their ancestors, folk heroes, animals, or their representations in idols or images, as if they are gods. To these representations, they offer respect and ritual offerings, burning incense, ritual papers, and paper objects to help maintain order and to bring good luck. This is, perhaps, why Chinese rarely become religious fanatics, evangelical, or driven to convert others. Above all, Chinese respect other people's religions as much as they respect their own.

Like most religions, there are rituals and moral teachings. Rituals are observed, learned, and practiced at home and in community temples or village ancestral halls. In the absence of ancestral halls in the United States, they perform rituals at miniature altars at home and in the place of business and in sanctuaries found in district and family associations in Chinatowns. Festivals and important dates in one's family are observed through rituals and banquets. Beliefs or teachings, to most Chinese, are simply ethical wisdom or precepts for living right or in harmony with nature or gods. They are taught through deeds, moral tales, and ethical principles, at home and in temples. Over the centuries, these teachings have combined major ideas and wisdom from Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism with local folk religions and village lores.

Employment and Economic Traditions

Before the 1882 Chinese exclusion law, Chinese could be found in all walks of life. However, with the rise of anti-Chinese movements and the enactment of anti-Chinese laws, Chinese were effectively driven out of most jobs and businesses competitive with whites. Until World War II, Chinese were left with jobs in laundries, Chinese restaurants, sweatshops, gift shops, and grocery stores located in Chinatowns. Even those who were American-born and college educated were unable to find jobs commensurate with their training.

World War II was a turning point for Chinese Americans. Not only were they recruited into all branches of military service, they were also placed in defense-related industries. In spite of racial prejudice, young Chinese Americans excelled in science and technology and made substantial inroads into many new sectors of the labor market during the war. Two significant postwar developments changed the fortune of Chinese Americans. First, the rise of the military industrial complex in suburban areas created opportunities for Chinese Americans in defenserelated industries. Second, there was the arrival of many highly educated Chinese immigrants from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, whose talents were immediately recognized; they were quickly recruited by the military industrial complex and leading research centers and universities.

In general, the intellectual immigrants settled down in middle-class suburbs near new industrial or research centers, such as Silicon Valley in Santa Clara County, California and NASA Johnson Space Center outside of Houston, Texas. Likewise, affluent pockets of Chinese Americans can be found in such metropolitan areas as Seattle, Minneapolis, Chicago, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, San Diego, and Dallas. Since the 1970s, some even used their talents to start their own businesses in the highly competitive high-tech industries. Among the best known are An Wang of Wang Laboratories, David Lee of Qume Corporation, Tom Yuen of AST, and Charles Wang of Computer Associates International. Many of the intellectual immigrants also became leading scientists and top engineers in the United States, giving rise to the false impression that the prewar oppressed Chinese working class had finally pulled themselves up by their own bootstraps. This is the misleading "model minority" stereotype that the media originated and has fiercely maintained since the late 1960s. These highly celebrated intellectuals, in fact, have little, politically, economically, or socially in common with the direct descendants of the prewar Chinese communities in big cities.

Among the post-1965 immigrants were also thousands who came to be reunited with their long-separated loved ones. Most of them settled in well-established, but largely disenfranchised, Chinese American communities in San Francisco, New York, Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, Oakland, and Los Angeles where they became the new urban working class. Many also became small entrepreneurs in neighborhoods throughout these cities, concentrating mostly in laundries, restaurants, and grocery stores. In fact, their presence in these three areas of small business has made them an integral part of the cityscape of American cities. Usually with little or no English, they pursued their "American dream" by working long hours, often with free labor from family members or cheap labor from relatives.

The Chinese American population is, therefore, bifurcated between the poor (working class) and the middle class (professionals and small business owners). The interests of these two groups coincide with each other over such issues as racism and access to quality education, but most of the time, they are at odds with each other. There is much debate over the China-Taiwan conflict, and, regarding housing and employment, their relations are frequently those of landlord-tenant and management-labor, typified by the chronic struggle over land use (e.g., the International Hotel in San Francisco's Chinatown) and working conditions in Chinatowns (e.g., the Chung Sai Sewing Factory, also in San Francisco's Chinatown) since 1970.

Politics and Government

Unlike European immigrants and African Americans since the Civil War, Chinese immigrants were denied citizenship, systematically discriminated against and disenfranchised until after World War II. Numerically far smaller than Euro-Americans and African Americans, Chinese Americans posed no political threat to the entrenched power, even after they were granted the right of naturalization after the war. They were routinely denied, de jure and de facto, political and civil rights. It was not until the late 1960s, under the militant leadership of younger Chinese Americans, that they began to mobilize for equal participation with the help of African Americans and in coalition with other Asian American groups.

Three key elements shaped the formation and development of the Chinese American community: racism, U.S.-China relations, and the interaction between these two forces. The intersection of American foreign policy and domestic racial politics compelled Chinese Americans to live under a unique structure of dual domination. They were racially segregated and forced to live under an apartheid system, and they were subject to the extraterritorial domination of the Chinese government, condoned, if not encouraged at times, by the U.S. government. Chinese Americans were treated as aliens and confined to urban ghettos and governed by an elite merchant class legitimated by the U.S. government and reinforced by the omnipresent diplomatic representatives from China. Social institutions, lifestyles, and political factionalism were reproduced and institutionalized. Conflict over homeland partisan disputes—including the dispute between the reform and revolutionary parties at the beginning of the twentieth century and between the Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek and Communists led by Mao Tse-tung in China—kept the community deeply divided. Such divisions drained scarce financial resources and political energy from pressing issues within the community and left behind a legacy of preoccupation with motherland politics and deep political cleavage to this date. During the Cold War, the extraterritorial domination intensified, as military dictators in Taiwan, backed by the United States, extended their repression into the Chinese American community in an effort to insure political loyalty and suppress political dissent.

The African American Civil Rights movement inspired and inaugurated a new era of ethnic pride and political consciousness. Joined by other Asian American groups, American-born, college-age Chinese rejected both the racist model of forced assimilation and the political and cultural domination of the Nationalist government in Taiwan. They also rejected second-class citizenship and the option of returning to Asia. Instead, they demanded liberation from the structure of dual domination. These college students and, later, young professionals contributed most significantly to raising the ethnic and political consciousness of Chinese Americans and helped achieve civil rights. Furthermore, they founded many social service agencies and professional, political, and cultural organizations throughout the United States. They also joined forces with other Asian American college students to push for the establishment of Asian American studies programs in major universities and colleges across the nation.

The politicization of Chinese Americans soon led to the founding of new civil rights and partisan political organizations. Most notable was the founding of Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA) in San Francisco in 1969, a civil rights organization that has been at the forefront of all major issues— employment, education, media, politics, health, census, hate crime, etc.—affecting Chinese Americans across the nation. By the 1970s, two national organizations, the Organization of Chinese Americans (OCA) and the National Association of Chinese Americans (NACA), were formed in most major cities to serve, respectively, middle-class Chinese Americans and Chinese American intellectuals. Likewise, local partisan clubs and Chinese American Democrats and Republicans were organized to promote Chinese American participation in politics and government.

By the 1980s, some middle-class Chinese Americans began to take interest in local electoral politics. They have enjoyed modest success in the races for less powerful positions, such as school boards and city councils. Among the notable political leaders to emerge were March Fong Eu, secretary of state of California, S. B. Woo, lieutenant governor of Delaware (1984-88), Michael Woo of Los Angeles City Council (1986-90), and Thomas Hsieh and Mabel Teng of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1988.

With increased interest in electoral politics came the demand for greater participation in other branches of government. In 1959 Delbert Wong became the first Chinese American to be appointed a municipal judge in Los Angeles. In 1966 Lim P. Lee was appointed postmaster of San Francisco, and Harry Low, a municipal judge. Low was later appointed to the Superior Court and the California Appellate Court. Also appointed to the municipal bench were Samuel Yee, Leonard Louie, Lillian Sing, and Julie Tang in San Francisco and Jack Bing Tso, James Sing Yip, and Ronald Lew in Los Angeles. Thomas Tang was appointed to the Ninth Circuit Court in 1977 and Elwood Lui to the federal district court in 1984.

Chinese Americans have been predominantly an urban population since the late nineteenth century. Their community has long been divided between the merchant elites and the working-class, and the influx of both poor and affluent immigrants since the late 1960s has deepened the division in the community by class, nativity, dialect, and residential location, giving rise not to just conflicting classes and public images, but also to conflicting visions in Chinese America. The sources of this open split can be traced to the changes in U.S. immigration laws and Cold War policies and to the arrival of diverse Chinese immigrants from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asian countries throughout the Cold War. The division has had serious political and social consequences as Chinese Americans from opposing camps seek political empowerment in cities with a deeply entrenched, white ethnic power structure and emerging African American forces.

Individual and Group Contributions

Chinese American contributions are significant and far-reaching. In general, it can be said that they contributed in labor to the economic development in the West in the second half of the nineteenth century and to science and technology in the second half of the twentieth century. Even though the nineteenth-century immigrants to the West Coast were mostly peasants working as contract laborers, their collective contribution to the building of the West has long been recognized by historians. Most notable was the completion of the transcontinental railway over the Sierra Nevada and the deserts of Nevada and Utah, and the building of the railroad network throughout the Southwest and into the Deep South. Less known, but no less significant, was the labor they provided for the mining of not just gold but also other minerals from the Pacific Coast to the Rocky Mountains; the construction of the canals, irrigation systems, and land claims that lay the foundation for the well-known and prosperous agribusiness of California; the groundbreaking work in fruit and vegetable farming and fishing industry; and the labor-intensive manufacturing industries, such as garments, shoes, woolen mills, and cigars, which provided the necessities of life in the developing West. Chinese labor was so timely, dependable, and efficient that Stanford historian Mary R. Coolidge, writing in 1909, concluded that "without [it] her [California's] material progress must long be postponed." Likewise, the UCLA historian Alexander Saxton, in a more recent book (1971), characterized the Chinese laborers as the "indispensable enemy" in California's economic development and politics in the nineteenth century.

LITERATURE

In the world of literature, Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan have captured the imagination of the United States with their writings based in part on their personal experiences and stories told in their families. Kingston is best known for her Women Warrior (1976), Chinamen (1977), and Tripmaster Monkey (1989), while Tan is known for her Joy Luck Club (1989) and The Kitchen God's Wife (1991). Other accomplished writers, to name a few, include Gish Jen ( Typical American ), David Wong Louie ( Pangs of Love ), and Faye Myenne Ng ( Bone ). Equally successful, in the world of Chinese-language readers, are literary works written in Chinese by Chinese American writers like Chen Ruoxi, Bai Xianyong, Yi Lihua, Liu Daren, and Nie Hualing, who are also widely read in Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, and Southeast Asia.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Equally important are the contributions Chinese Americans made to postwar U.S. accomplishments in science and technology. As mentioned above, one of the most outstanding features of the postwar Chinese immigration is the migration of Chinese intellectuals from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Not only did they boost the large pool of scientists and engineers needed in the military-industrial complex throughout the Cold War, they also emerged as leading scientists and engineers in virtually all major disciplines in research laboratories in industries and research universities. For example, Chinese American scientists and engineers constitute a significant work force in the Silicon Valley and in aerospace centers in Seattle, Los Angeles/Long Beach, and San Diego, as well as in the national research laboratories of Lawrence Livermore, California; Los Alamos, New Mexico; Argonne Laboratory in Illinois; Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California; and NASA Space Centers in Houston, Texas, and Cape Canaveral, Florida. Chinese Americans are also employed in the laboratories of IBM, RCA, Bell Lab, GE, Boeing, 3M, Westinghouse, and in major research universities, from MIT to the University of California, Berkeley.

Many distinguished Chinese American scientists and engineers have received national and international recognition. For example, Chinese Americans who have received Nobel Prizes include: Chen-ning Yang, Cheng-tao Lee, and Tsao-chung Ting in physics and Yuan-tse Lee in chemistry. In mathematics, Shiing-shen Chern, Sing-tung Yao, and Wu-I Hsiang are ranked among the top in the world. In the biological sciences, Cho-hoe Li, Ming-jue Zhang, and Yuet W. Kan have all received honors and awards. The leading American researcher in superconductivity research is Paul Chu. In engineering, T. Y. Lin, structural engineer, received the Presidential Science Award in 1986. Others include Kuan-han Sun, a radiation researcher with Westinghouse; Tien Chang-lin, a mechanical engineer and chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley; Henry Yang, an aerospace engineer and the chancellor of the University of California, Santa Barbara; and Steven Chen, the leading researcher on the next generation of supercomputers.

Among the Chinese American women with national and international reputations in science are Ying-zhu Lin in aeronautics and aeronautical engineering, recipient of the Achievement Award for women engineers in 1985, and Chien-Hsiung Wu in physics.

In March 1997, Wen Ho Lee, an atomic scientist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory near Albuquerque, New Mexico, was arrested on suspicion of spying for China. Wen Ho Lee was fired for unspecified security violations, but in early May of 1999, federal officials revealed that Wen Ho had transferred secret nuclear weapons computer programs from the Los Alamos computer system to his own desktop computer. Wen Ho denied the charges that he was a spy and claimed that he let no one see the nuclear weapons computer program. In a prepared statement issued on May 6, 1999, Wen Ho said he would "not be a scapegoat for alleged security problems at our country's nuclear laboratories" and he denied that he ever gave classified information to unauthorized persons.

THEATER, FILM, AND MUSIC

Frank Chin, Genny Lim, and David Henry Hwang have all made lasting contributions to the theater. Among the best known plays of Hwang are FOB, The Dance and the Railroad, Family Devotions, and M. Butterfly. Several films of Wayne Wang, Chan is Missing, Dim Sum, Eat a Bowl of Tea, and Joy Luck Club, have received critical acclaims. Less famous, but no less important, are the unique Chinese American themes and sounds of jazz compositions and recordings of Fred Ho in New York and Jon Jang in San Francisco.

VISUAL ARTS

Besides their enormous contributions to science and technology, many Chinese Americans also excel in art and literature. Maya Ying Lin is already a legend in her own time. At 21, while an architecture student at Yale University, she created the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., one of the most frequented national monuments. After this enormous success, she went on to design the Civil Rights Memorial in Atlanta, a giant outdoor sculpture commemorating the history of women at her alma mater, and a monumental sculpture at the New York Pennsylvania Railroad Station.

Just as impressive, are the architectural wonders of I. M. Pei. Among his best known works are the East Wing of the National Art Gallery in Washington, D.C., the John F. Kennedy Library at Harvard University, the Boston Museum and the John Hancock Building in Boston, Dallas Symphony Hall, the modern addition to the Louvre in Paris, the Bank of China in Hong Kong, and the Xiangshan Hotel in Beijing.

Anna Sui (1955 – ), a native of Detroit, is a famous Chinese American fashion designer. Known for her stylistic versatility, Sui has dabbled in everything from 1960s fashion to formal evening wear.

Media

Chinese-language newspapers have always played an important role in the Chinese American community. Newspapers may be found in most major Chinatowns, from Honolulu to New York. San Francisco, however, has long been the national center for Chinese American newspapers.

The Gold Hills News, the first weekly to be published in San Francisco, was founded in April of 1854. The following year, Rev. William Speer, a Presbyterian missionary to Chinatown, published the first bilingual weekly, Tung Ngai San-Luk ( The Oriental ). A year later, in 1856, the Chinese Daily News, the first Chinese daily in the world, began circulation in Sacramento, California.

Unfortunately, technical and financial difficulties made success in print medium elusive. Most did not survive long. It was not until the early twentieth century, under the influence of Chinese nationalism and opposing political parties seeking support among Chinese in the United States, that newspapers in Chinatown flourished and endured for several decades. The factions with influential papers in San Francisco were Hongmen's Datung Ribao ( Chinese Free Press ), Chung Sai Daily, a neutral daily, edited by Ng Poon Chew, Shaonian Zhongguo Zhen Bao ( Young China Morning Paper ), founded by Sun Yat-sen, and Shijie Ribao ( The Chinese World ), a proreform party paper.

The next round of blossoming Chinese-language papers began modestly in the early 1970s and, aided by computers, satellite telecommunication, and new printing technology, grew into a major battle in the early 1980s among giant national dailies. The national dailies, printed and distributed simultaneously in major cities in the United States, included The World Journal ( Shijie Ribao ), China Times ( Zhongguo Shiba o), International Daily News ( Guoji Ribao ), Sing Tao Daily, and Centre Daily ( Zhong Bao ). To be added to this list are two other types of dailies: local dailies and dailies transmitted from Hong Kong and Taiwan. In addition to these nationally distributed dailies are numerous local dailies and weeklies and monthlies distributed both locally and nationally. The most notable weeklies in San Francisco have been Chinese Pacific Weekly ( Taipingyang Zhoubao ), East-West Chinese American Weekly (Dongxi Bao), an independent bilingual paper, and Asian Week, an English-only weekly.

Stiff competition for a small pool of Chinese readership and advertising dollars soon eliminated the first of several local dailies and weeklies and some of the national dailies by the late 1980s. Satellite-transmitted dailies from Hong Kong, however, continue to thrive in major cities in the United States.

Chinese American Citizens Alliance.

Newsletter of group with same name featuring news of interest to Chinese Americans.

Contact: Vera Lee Goo, Editor.

Address: 1044 Stockton Street, San Francisco, California 94108.

Telephone: (415) 434-2222.

Chinese Daily News.

Formerly World Journal.

Contact: Shihyaw Chen, Editor.

Address: 1588 Corporate Center Drive, Monterey Park, California 91754.

Telephone: (213) 268-4982.

Fax: (213) 265-3476.

The Chinese Press.

Address: 15 Mercer Street, New York, New York 10013.

Telephone: (212) 274-8282.

Sampan.

The only bilingual newspaper in New England serving the Asian community.

Contact: Catherine Anderson or Carmen Chan.

Address: Asian-American Civic Association, 90 Tyler Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02111.

Telephone: (617) 426-9492.

Fax: (617) 482-2315.

Sing Tao Daily.

Contact: Tim S. Lau, Vice President.

Address: 215 Littlefield Avenue, South San Francisco, California 94080.

Telephone: (650) 872-1177; or (800) SINGTAO.

Fax: (650) 872-0234.

RADIO

Global Communication Enterprises, New York; Huayu Radio Broadcast, San Francisco.

TELEVISION

Chinese World Television, New York; Hong Kong Television Broadcasts, U.S.A., Los Angeles; United Chinese TV, San Francisco; Hua Sheng TV, San Francisco; Pacific TV Broadcasting Co., San Francisco; and Channel 26, San Francisco.

Organizations and Associations

Nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants established most traditional Chinese social organizations in Chinatowns. Most notable were the district associations ( huiguan ) and family name associations ( gongsuo ). Together, they formed the Consolidated Chinese Benevolent Association (CCBA) or the Chinese Six Companies. Before World War II, they were recognized as the leaders and spokesmen of the Chinese American community. Most of these organizations remain today. However, with the passage of time and the rise of new needs and interests, several modern organizations have emerged. Most notable among these are Christian churches of different denominations, secret societies ( tongs ), Chinese schools for different interest groups, trade organizations, guilds, and unions (laundry, garment, cigar, shoes, restaurant, etc.), recreation and youth clubs (YMCA and YWCA), political parties in China (earlier, Chee Kong Tong, Baohuanghui, Tungmenghui, and later, Kuomintang and Xienzhengdang), social and cultural societies, and newspapers. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1908, and the Chinese Hospital was established in 1925. Since the 1960s, new types of organizations have risen and proliferated.

Chinese American Citizens Alliance (CACA).

A national organization founded early in the twentieth century to fight for Chinese American rights, with chapters in different Chinatowns.

Contact: Collin Lai, President.

Address: 1044 Stockton Street, San Francisco, California 94108.

Telephone: (415) 982-4618.

Chinese American Forum (CAF).

Cultivates understanding among U.S. citizens of Chinese American cultural heritage. Publishes a quarterly.

Contact: T. C. Peng, President.

Address: 606 Brantford Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland 20904.

Telephone: (301) 622-3053.

Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA).

The oldest national Chinese organization in Chinatown, with affiliates in all Chinatowns.

Contact: Yut Y. Eng, President.

Address: 843 Stockton Street, San Francisco, California 94108.

Telephone: (415) 982-6000.

E-mail: ccba@mindspring.com.

Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA).

The leading civil rights organization of Chinese in the United States.

Contact: Henry Der, Executive Director.

Address: 17 Walter U. Lum Place, San Francisco, California 98108.

Telephone: (415) 274-6750.

Organization of Chinese Americans (OCA).

A national organization committed to promoting the rights of Chinese Americans, with chapters throughout the United States and a lobbyist office in Washington, D.C. Publishes newsletter OCA Image.

Contact: Daphne Quok, Executive Director.

Address: 1001 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 707, Washington, D.C. 20036.

Telephone: (202) 223-5500.

Museums and Research Centers

Center for Chinese Studies (University of Michigan).

Economics, politics, law, literature, and social structure of China; also Chinese history, philosophy, literature, linguistics, and art history. Promotes and supports research in social sciences and humanities relating to China, past and present, by faculty members, graduate students, and associates of the center.

Address: 1080 South University, Suite 3668, Ann Arbor, Michigan 481091106.

Contact: Dr. Ernest P. Young, Director.

Telephone: (734) 764-6308.

Fax: (734) 764-5540.

E-mail: chinese.studies@umich.edu.

Online: http://www.umich.edu/~iinet/ccs/index.html .

Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco.

A community-based cultural and educational facility, this organization provides space for exhibits, performing arts, conferences, classrooms, and meetings.

Contact: Manni Liu, Acting Executive Director/Curator.

Address: 750 Kearney Street, 3rd Floor, San Francisco, California 94108.

Telephone: (415) 986-1822.

Fax: (415) 986-2825.

E-mail: info@ccc.org.

Online: http://www.ccc.org .

Chinese Historical Society of America.

Devoted to the study of the Chinese people in the United States and the collection of their relics. Ethnic and historical interests of the society are published in its bulletin.

Contact: Philip Choy, President.

Address: 650 Commercial Street, San Francisco, California 94133.

Telephone: (415) 391-1188.

Fax: (415) 3911150

Museum of Chinese in the Americas (MoCA).

Founded in 1980 as the New York Chinatown History Project; adopted its present name in 1995. Strives "to reclaim, preserve, and broaden understanding about the diverse history of Chinese people in the Americas." Included is the most extensive collection of Chinese-language newspapers in the United States.

Address: 70 Mulberry Street, 2nd Floor, New York, New York 10013.

Telephone: (212) 619-4785.

Sources for Additional Study

Claiming America: Constructing Chinese American Identities During the Exclusion Era, edited by K. Scott Wong and Sucheng Chan. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998.

Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943, edited by Sucheng Chan. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Kwong, Peter. Chinatown, NY: Labor & Politics, 1930-1950. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979.

Lowen, James W. The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Lydon, Sandy. Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. Capitola, California: Capitola Book Co., 1985.

Ma, L. Eve Armentrout. Revolutionaries, Monarchists, and Chinatowns: Chinese Politics in the Americas and the 1911 Revolution. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990.

McClain, Charle. In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle Against Discramination in Nineteenth-Century America. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

Nee, Victor G., and Brett de Barry. Longtime Californ': A Documentary Study of an American Chinatown. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1971.

Takaki, Ronald (adapted by Rebecca Stefoff). Ethnic Islands: The Emergence of Urban Chinese America. New York: Chelsea House, 1994.

Tsai, Shih-shan Henry. China and the Overseas Chinese in the United States, 1868-1911. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1983.

Becky

Andrew Morgan

Do you guys even answer questions on this website? Need answers and I need them today , please write back.

I don't expect a quick answer, but I thought I would at least try. Boy, you sure get some clowns responding to you, making impertinent comments and demands. Too lazy to do their own research! I was lucky to find this. It gave me so much more perspective than the other articles I found.

I am writing a paper on Chinese American contributions in general. I chose that group because my husband is Chinese American on one side (German on the other). Eurasian, all too assimilated into the mainstream culture, I would say.

I don't expect a quick answer, but I thought I would at least try. Boy, you sure get some clowns responding to you, making impertinent comments and demands. Too lazy to do their own research! I was lucky to find this. It gave me so much more perspective than the other articles I found.

I am writing a paper on Chinese American contributions in general. I chose that group because my husband is Chinese American on one side (German on the other). Eurasian, all too assimilated into the mainstream culture, I would say.

Reg,

Wysteria

1)what is the chinese-american's characterestic with respect to communication, space, silence, closeness,in relation to time, language, eye contact,touch, and expression of pain?

thanks!