Hopis

by Ellen French and Richard C. Hanes

Overview

The westernmost of the Pueblo Indian tribes, the independent Hopi (HO-pee) Nation is the only Pueblo tribe that speaks a Shoshonean language of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family. "Hopi" is a shortened form of the original term Hopituh-Shi-nu-mu, for which the most common meaning given is "peaceful people." The Hopis have also been referred to as the Moqui, based on what the Spanish called them. The Hopi reservation, almost 2.5 million acres in size and located in northeastern Arizona near the Four Corners area just east of the Grand Canyon, is surrounded completely by the Navajo reservation. The Hopis inhabit 14 villages, most of which are situated atop three rocky mesas (called First Mesa, Second Mesa, and Third Mesa) that rise 600 feet from the desert floor. Estimated at 2,800 in 1680, the Hopi Nation had 7,360 members in 1990, about 1,000 of whom lived off the reservation. The Hopies are ancient, having lived continuously in the same place for a thousand years. They are also a deeply religious people, whose customs and yearlong calendar of ritual ceremonialism guide virtually every aspect of their lives. Although some concessions to modern convenience have been made, the Hopis have zealously guarded their cultural traditions. This degree of cultural preservation is a remarkable achievement, facilitated by isolation, secrecy, and a community that remains essentially closed to outsiders.

HISTORY

According to Suzanne and Jake Page's book Hopi , the Hopis are called "the oldest of the people" by other Native Americans. Frank Waters wrote in The Book of the Hopi that the Hopis "regard themselves as the first inhabitants of America. Their village of Oraibi is indisputably the oldest continuously occupied settlement in the United States." While Hopi oral history traces their origin to a Creation and Emergence from previous worlds, scientists place them in their present location for the last thousand years, perhaps longer. In her book The Wind Won't Know Me, Emily Benedek wrote that "anthropologists have shown that the cultural remains present a clear, uninterrupted, logical development culminating in the life, general technology, architecture, and agriculture and ceremonial practices to be seen on the three Hopi mesas today." Archaeologists definitively place the Hopis on the Black Mesa of the Colorado Plateau by 1350.

The period from 1350 to 1540 is considered the Hopi ancestral period, marked primarily by the rise of village chieftains. A need for greater social organization arose from increased village size and the first ritual use of kivas, the underground ceremonial chambers found in every village. Additionally, coal was mined from mesa outcroppings, requiring unprecedented coordination. The Hopis were among the world's first people to use coal for firing pottery.

The complex Hopi culture, much as it exists today, was firmly in place by the 1500s, including the ceremonial cycle, the clan and chieftain social system, and agricultural methods that utilized every possible source of moisture in an extremely arid environment. The Hopis' "historical period" began in 1540, when first contact with Europeans occurred. In that year a group of Spanish soldiers led by the explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado arrived, looking for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. After a brief, confrontational search produced no gold, the Spanish destroyed part of a village and left.

The Hopis were not molested further until 1629, when the first Spanish missionaries arrived, building missions in the villages of Awatovi, Oraibi, and Shungopavi. Historians speculate the Hopis pretended to adopt the new religion while practicing their own in secret. Hopi oral history confirms this interpretation. Rebelling finally against the Spanish yoke of religious oppression, the Hopis joined the rest of the Pueblo people in a unified revolt in 1680. During this uprising, known as the Pueblo Revolt, the Indians took the lives of Franciscan priests and Spanish soldiers and then besieged Santa Fe for several days. When the Hopis finally returned to their villages, they killed all the missionaries.

The Hopis then moved three of their villages to the mesa tops as a defensive measure against possible retaliation. The Spanish returned to reconquer the Rio Grande area in 1692. Many Rio Grande Pueblo Indians fled west to Hopi, where they were welcomed. Over the next few years, many living in Awatovi invited the Spanish priests back, a situation that caused a serious rift between those who wanted to preserve the old ways and those who embraced Christianity. Finally, in 1700 Hopi traditionalists killed all the Christian men in Awatovi and then destroyed the village. The destruction of Awatovi signaled the end of Spanish interference in Hopi life, although contact between the groups continued.

MODERN ERA

In response to the growing problem of Navajo encroachment on traditional Hopi land, President Chester A. Arthur established the Hopi reservation in 1882, setting aside 2,472,254 acres in northeastern Arizona for "Moqui and other such Indians as the Secretary of the Interior may see fit to settle thereon." The Hopi reservation was centered within a larger area (considered by the Hopis also to be their ancestral land) that was designated the Navajo reservation. As populations increased, the Navajo expanded their settlements well beyond their own borders, encroaching even more on the Hopi reservation. Despite the executive order, this situation continued for many decades. The Hopis complained, but the government failed to act, and the Navajo continued to overrun Hopi lands until they had taken over 1,800,000 acres of the original Hopi designation. The Hopis were left with only about 600,000 acres. Recognizing the problem, Congress finally passed the Navajo-Hopi Settlement Act in 1974, which returned 900,000 acres to the Hopis. The dispute over resettlement and the remaining 900,000 original acres continues, however, as a number of Navajo families have refused to leave due to ancestral ties to the land. A 1975 film titled Dineh: The People, produced by Jonathan Reinis and Stephen Hornick, examined the relocation of Navajo from the joint-use area around the Hopi reservation, looking at the many sociocultural issues it raised. A more recent film, In the Heart of Big Mountain (1988) , produced by Sandra Sunrising Osawa, looks at the background and history of the land dispute and the sacredness of the Big Mountain area to affected Navajo. Thomas Banyacya Sr. (b.1910), born in New Oraibi, became an outspoken traditionalist Hopi elder in opposition to Navajo relocation.

Another ongoing issue facing the Hopi concerns the preservation of the Hopi Way. Two 1980s films examine the Hopi Way. A 1983 film directed by Pat Ferrero takes an in-depth look at the Hopi

These modern-day concerns have split the tribe into two factions, the Traditionalists and the Progressives. Traditionalists fear the erosion of Hopi culture by white cultural influences. Progressives feel that adoption of some aspects of modern American culture is necessary if the tribe is to survive and grow economically.

Acculturation and Assimilation

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

By the end of the twentieth century, the Hopi tribe was considered one of the more traditional Indian societies in the continental United States. As far back as they can be reliably traced by archeologists (to the period called Pueblo II, between 900 and 1100), the Hopis have been sedentary, living in masonry buildings. Their villages consisted of houses built of native stone, arranged around a central plaza containing one or more kivas. Hopi villages are arranged in much the same way today. During the Pueblo III Period (1100 to 1300), populations in the villages grew as the climate became more arid, making farming more difficult. The village buildings grew in size as well, some containing hundreds of rooms. During the Pueblo IV Period, the Hopi ancestral period from 1350 to 1540, the houses, made "of stone cemented with adobe and then plastered inside were virtually indistinguishable from the older houses of present-day Hopi, except that they were often multistoried," according to Page and Page. They added that the houses of that period contained rooms with specific functions, such as storage or grinding corn, and that kiva design was "nearly identical" to that of today. The houses and kivas of this period were heated with coal, which was also used for firing pottery. Today the Hopis occupy the older masonry houses as well as modern ones. The kiva remains largely as it was in ancient times: a rectangular room built of native stone, mostly below ground. "Sometimes," wrote Waters, "the kiva is widened at one end, forming the same shape as the T-shaped doorways found in all ancient Hopi ruins." This design is intended to echo the hairstyle of Hopi men, which generally forms a "T" shape. The kiva contains an altar and central fire pit below the roof opening. A ladder extends above the edge of the roof. When not in use for ceremonies, kivas are also used as meeting rooms.

The number four has great significance in the Hopi religion, so many ritual customs often call for repetitions of four. In accordance with Hopi tradition, both boys and girls were initiated into the kachina cult between the ages of eight and ten. Leitch wrote that the rite included "fasting, praying, and being whipped with a yucca whip. Each child had a ceremonial mother (girls) or father (boys) who saw them through the ordeal." She also noted, "All boys were initiated into one of the four men's societies Kwan, Ahl, Tao, or Wuwutcimi, usually joining the society of their ceremonial father. These rites commonly occurred in conjunction with the Powama ceremony, a four-day tribal initiation rite for young men, usually held at planting time." A tradition no longer observed is the prepuberty ceremony for ten-year-old girls, which involved grinding corn for an entire day at the girl's paternal grandmother's house. "At the onset of menses," Parsons wrote in 1950, "girls of the more conservative families go through a puberty ceremony marked by a four-day grinding ordeal." The girl would also receive a new name and would then occasionally assume the squash blossom hairstyle, the sign of marriageability.

TRADITIONAL STORIES

A tradition of oral literature has been crucial to the survival of the Hopi Way because the language has remained unwritten until recent years. The oral tradition has made it possible to foster Hopi pride during modern times and to continue the custom, ritual, and ceremony that sustain the religious beliefs that are the essence of the Hopi Way. The body of Hopi oral literature is huge.

CUISINE

The Hopis have long been sedentary agriculturalists, with the men handling the work of cultivating and harvesting the crops. A great drought occurred from 1279 to 1299, requiring the Hopis to adopt inventive farming methods still in use today. Every possible source of moisture is utilized. The wind blows sand up against the sides of the mesas, forming dunes that trap moisture. Crops are then planted in these dunes. The Hopis also plant in the dry washes that occasionally flood, as well as in the mouths of arroyos. In other areas they irrigate crops by hand.

In the ancestral period, wild game was more plentiful, and Hopi men hunted deer, antelope, and elk. They also hunted rabbit with a boomerang. Page and Page listed corn, squash, beans, and some wild and semi-cultivated plants such as Indian millet, wild potato, piñon, and dropseed as staples of this period. They also noted that salt was obtained, although not without difficulty, by making long excursions to the Grand Canyon area. Barbara Leitch wrote in A Concise Dictionary of Indian Tribes of North America that the women gathered "pinenuts, prickly pear, yucca, berries, currants, nuts, and various seeds." Hopi women also made fine pottery, a craft that still flourishes today. The Hopis raised cotton in addition to the edible crops, and the men, Leitch wrote, "spun and wove cotton cloth into ceremonial costumes, clothing, and textiles for trade." In the sixteenth century the Spanish introduced wheat, onions, peaches and other fruits, chiles, and mutton to the Hopi diet.

The Hopis continue to depend on the land. Wild game had dwindled significantly in the region by 1950, leaving only rabbit as well as a few quail and deer. Modern Hopi farmers still use the old methods, raising mainly corn, melons, gourds, and many varieties of beans. Corn is the main crop, and the six traditional Hopi varieties are raised: yellow, blue, red, white, purple, and sweet. All have symbolic meaning stemming from the Creation story. A corn roast is an annual ritual, and corn is ground for use in ceremonies as well as to make piki, a traditional bread baked in layers on hot stones. A 1983 film Corn Is Life, documents the importance of corn to Hopi culture and its religious significance. The film shows traditional activities in planting, cultivating, harvesting, and preparing corn, including the baking of piki bread on hot, polished stone.

TRADITIONAL APPAREL

In earlier times Hopi men wore fur or buckskin loincloths. Some loincloths were painted and decorated with tassels, which symbolized falling rain. The men also raised cotton and wove it into cloth, robes, blankets, and textiles. These hand-woven cotton blankets were also worn regularly. The Hopis were reported in 1861 as being wrapped in blankets with broad white and dark stripes. At that time, women also commonly wore a loose black gown with a gold stripe around the waist and at the hem. Men wore shirts and loose cotton pants, covered with a blanket wrap. During the ritual ceremonies and dances, Hopi men wear elaborate costumes that include special headdresses, masks, and body paints. These costumes vary according to clan and ceremony.

Women had long hair, but marriageable girls wore their hair twisted up into large whorls on either side of their heads. These whorls represented the squash blossom, which was a symbol of fertility. This hairstyle is still worn by unmarried Hopi girls but due to the amount of time required to create it, the style is reserved for ceremonial occasions. The hairstyle for married women was either loose or in braids. The traditional hairstyle for Hopi men, after which kiva design was sometimes patterned, was worn with straight bangs over the forehead and a knot of hair in the back with the sides hanging straight and covering the ears. This style of bangs is still seen among traditional Hopi men.

Hopi women and girls today wear a traditional dress, which is black and embroidered with bright red and green trim. A bride, as in early days, wears a white robe woven of white cotton by her uncles. This bridal costume actually consists of two white robes. The bride wears a large robe with tassels that symbolize falling rain. A second, smaller robe, also with tassels, is carried rolled up in a reed scroll called a "suitcase" in English. When the woman dies, she will be wrapped in the suitcase robe.

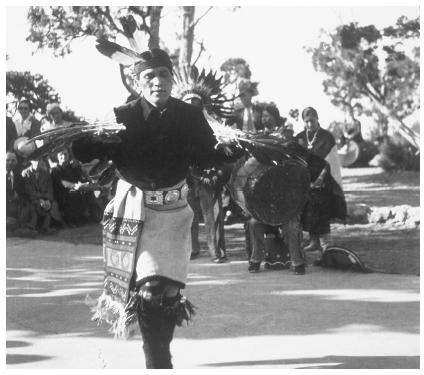

DANCES AND SONGS

Benedek wrote that "in spirit and in ceremony, the Hopis maintain a connection with the center of the earth, for they believe that they are the earth's caretakers, and with the successful performance of their ceremonial cycle, the world will remain in balance, the gods will be appeased, and rain will come." Central to the ceremonies are the kiva, the paho, and the Corn Mother. The kiva is the underground ceremonial chamber. Rectangular in shape (the very ancient kivas were circular), the kiva is a symbol of the Emergence to this world, with a small hole in the floor leading to the underworld and a ladder extending above the roof opening, which represents the way to the upper world. Kivas are found in various numbers in Hopi villages, always on an east–west axis, sunk into the central plaza of a village. Following the secret ceremonies held inside the kiva, ceremonial dances are performed in the plaza. The paho, a prayer feather, usually that of an eagle, is used to send prayers to the Creator. Pahos are prepared for all kiva ceremonies. Corn has sustained the Hopis for centuries, and it plays a large role in Hopi ceremonies, such as in the sprinkling of cornmeal to welcome the kachinas to the Corn Mother. Waters described the Corn Mother as "a perfect ear of corn whose tip ends in four full kernels." It is saved for rituals.

The kachinas are spirits with the power to pass on prayers for rain and are mostly benevolent. Humans dressed and masked as these spirits perform the kachina dances, which are tied to the growing season, beginning in March and lasting into July. Kachina dolls, representing these gods, are carved and sold as crafts today, although they were originally toys for Hopi children. One of the most important ceremonials is held at the winter solstice. This ceremony, Soyal, as the first ceremony of the year and the first kachina dance, represents the second phase of Creation. The Niman ceremony, or the Home Dance, is held at the Summer Solstice, in late July. At that point the last of the crops have been planted and the first corn has been harvested. The Home Dance is the last kachina dance of the year. Although other ceremonial dances are also religious, they are less so than the kachina rituals. These other dances include the Buffalo Dance, held in January to commemorate the days when the buffalo were plentiful and Hopi men went out to the eastern plains to hun them; the Bean Dance, held in February to petition the kachinas for the next planting; and the Navajo Dance, celebrating the Navajo tribe. While the well-known Snake Dance is preceded by eight days of secret preparation, the dance itself is relatively short, lasting only about an hour. During this rite the priests handle and even put in their mouths unresistant snakes gathered from the desert. Non-Hopi experts have tried to discover how the priests can handle snakes without being bitten, but the secret has not been revealed. At the conclusion of the dance the snakes are released back into the desert, bearing messages for rain. The Snake and Flute Dances are held alternately every other year. The Flute Dance glorifies the spirits of those who have passed away during the preceding two years. In addition, the Basket Dance and other women's dances are held near the end of the year. The Hopi ceremonial cycle continues all year. The ritual ceremonies are conducted within the kivas in secrecy. The plaza dances that follow are rhythmic, mystical, and full of pageantry. Outsiders are sometimes allowed to watch the dances.

HOLIDAYS

Traditional ceremonies are performed as instructed in sacred stories and relate to most aspects of daily Hopi life. Such occasions include important times in an individual's life, important times of the year, healing, spiritual renewal, bringing rain, initiation of people into positions, and for thanksgiving. Hopi ceremonies included the Flute ceremony, New Fire ceremony, Niman Kachina ceremony, Pachavu ceremony, Powamu ceremony, Snake-Antelope ceremony, Soyal, and Wuwuchim ceremony.

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

Page and Page stated that much of Hopi healing is psychic but that the Hopis also utilize many herbal remedies. The Hopis are quite knowledgeable about the various medicinal properties of certain plants and herbs. Ritual curing, however, is done by several societies, including the kachina society. Parsons wrote, "The Kachina cult is generally conceived as a rain-making, crop-bringing cult; but it has also curing or health-bringing functions." She added that "On First Mesa kachina dances (including the Horned water serpent and the Buffalo Dance) may be planned for afflicted persons." In addition to holding dances expressly for sick people, for some illnesses the cure is administered by a specific society. For example, snakebite is treated by the Snake society on First Mesa, according to Parsons, and rheumatism is treated by the Powamu society, which then inducts the afflicted into the society. Other cures are less logical to an outsider. "On First Mesa," Parsons wrote, "lightning-shocked persons and persons whose fields have been lightning-struck join the Flute society. A lightning-shocked man is called in to cure earache in babies." Other rituals include the practice of "sucking out" the disease, usually when dealing with sick infants and children. Cornmeal is actually held in the mouth during this procedure, and then the curer "spits away" the disease. The Hopis also utilize modern medical science, doctors, and hospitals. A government hospital was established in 1913. Now, the Office of Native Healing Services is located in nearby Window Rock, Arizona. In the late 1990s a new health care center was planned for First Mesa.

Language

The Hopis speak several dialects of a single language, Hopi, with the exception of the village of Hano, where the members speak Tewa, which is derived from the Azteco-Tanoan linguistic family. Waters noted in 1963 that "Hopi is not yet a commonly written language, perhaps because of the extreme difficulty in translation, as pointed out by Benjamin Lee Whorf, who has made a profound analysis of the language." Despite being unwritten and untranslated, the strong Hopi oral tradition has preserved and passed down the language. Most Hopis today, including the younger generations, speak both Hopi and English. Both Arizona state universities began developing a Hopi writing system with a dictionary containing over 30,000 words.

COMMON WORDS AND EXPRESSIONS

Some Hopi words and phrases include: tiva— dance; tuwaki— shrine in the kiva; kahopi— not Hopi; kachada— white man; Hotomkam— Three Stars in Line (Orion's Belt); kachinki— kachina house; Hakomi?— Who are you?; and, Haliksa'I— Listen, this is how it is.

Family and Community Dynamics

EDUCATION

Hopi children gain their education through available formal school systems and through traditional educational activities in such places as kivas. Education is provided through local public schools, federal government schools, local village schools, private schools, and kivas. Between 1894 and 1912, schools were established near Hopi villages. But until the late twentieth century, children had to leave home to attend government-sponsored or private off-reservation boarding high schools. In 1985, new Hopi middle and high schools were opened for all tribal students. The on-reservation schools have facilitated traditional education by having students live at home, attending year-round village rituals and ceremonies. The traditional education begins in earnest around age of eight, with a series of initiation rites. The young are taught the Hopi Way, composed of traditional principles and ethics and the value of kinship systems.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

The social organization of traditional Hopi society is based on kinship clans determined through the woman's side of the family. The clans determine various kinds of social relations of individuals throughout their lives, including possible marriage partners and their place of residence. Women own the farming and garden plots, though men are responsible for the farming as well as the grazing of sheep and livestock. Women are also centrally involved in Hopi arts and crafts. By tradition the women's products are specialized and determined by their residence. Women make ceramics on First Mesa, coiled basketry on Second Mesa, and wicker basketry on Third Mesa. Hopi men do the weaving.

COURTSHIP AND WEDDINGS

Many marriage customs are still observed, but others have fallen into disuse. Fifty years ago, for example, courtship was an elaborate procedure involving a rabbit hunt, corn grinding, and family approval of the marriage. The bride was married in traditional white robes woven for the occasion by her uncles. The couple lived with the bride's mother for the first year. Today the courtship is much less formal. The couple often marry in a church or town and then return to the reservation. Since not all men know how to weave anymore, Page and Page pointed out that it may take years for the uncles to produce the traditional robes. They also described several marriage customs still in practice, however. These include a four-day stay by the bride with her intended in-laws. During this time she grinds corn all day and prepares all the family's meals to demonstrate her culinary competence. Prior to the wedding, the aunts of both the bride and groom engage in a sort of good-natured free-for-all that involves throwing mud and trading insults, each side suggesting the other's relative is no good. The groom's parents wash the couple's hair with a shampoo of yucca in a ritual that occurs in other ceremonies as well. A huge feast follows at the bride's mother's house. Once married, the bride wears her hair loose or in braids.

Clan membership plays a role in partner selection. The rule against marrying another member of the same clan has prevented interbreeding, keeping genetic lines strong. Although marriage into an associated clan was forbidden as well, Page and Page suggest that this tradition is breaking down. Marriage to non–tribal members is extremely rare, a fact that has helped preserve Hopi culture. The clan system is matrilineal, meaning that clan membership is passed down through the mother. One cannot be Hopi without a clan of birth, so if the mother is not Hopi, neither will her children be. Adoption into the tribe is also extremely rare.

FUNERALS

Old age among the Hopis is considered desirable, because it indicates that the journey of life is almost complete. The Hopis have a strong respect for the rituals of death, however, and it is customary to bury the dead as quickly as possible because the religion holds that the soul's journey to the land of the dead begins on the fourth day after death. Any delay in burial can thus interfere with the soul's ability to reach the underworld. The ritual called for the hair of the deceased to be washed with the yucca shampoo by a paternal aunt. Leitch added that the hair was then decorated with prayer feathers and the face covered with a mask of raw cotton, symbolizing clouds. The body was then wrapped—a man in a deerskin robe, a woman in her wedding robe—and buried by the oldest son, preferably on the day or night of death. Leitch wrote that "the body was buried in a sitting position along with food and water. Cornmeal and prayersticks were later placed in the grave." A stick is inserted into the soil of a grave as an exit for the soul. If rain follows, it signifies the soul's successful journey.

INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER TRIBES

The Hopis have maintained historical relations with the Zuñi as well as the Hano and Tewa groups in the Rio Grande River valley to the east. During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Pueblo groups united to drive Spanish influence out of the region. Moreover, extensive trading networks existed among the groups prior to the revolt. The complex land issues with the Navajo have led to complex relations. The Hopi elective government have fought for defense of their original reservation, while traditionalists support the Navajo families' efforts to remain on the disputed lands.

NAMING CEREMONY

Page and Page explained the special rituals observed when naming a new baby. A newborn is kept from direct view of the sun for its first 19 days. A few days prior to the naming, the traditional Hopi stew is prepared at the home of the maternal grandmother, who figures prominently in the custom. The baby belongs to her of his mother's clan but is named for the father's. In the naming ritual, the grandmother kneels and washes the mother's hair, then bathes the baby. The baby is wrapped snugly in a blanket, with only its head visible. With the baby's Corn Mother, the grandmother rubs a mixture of water and cornmeal on the baby's hair, applying it four times. Each of the baby's paternal aunts then repeats this application, and each gives a gift and suggests a name. The grandmother chooses one of these names and then introduces the baby to the sun god just as the sun comes up. A feast follows.

Religion

The Hopi religion is a complex, highly developed belief system incorporating many gods and spirits, such as Earth Mother, Sky Father, the Sun, the Moon, and the many kachinas, or invisible spirits of life. Waters described this religion as "a mytho-religious system of year-long ceremonies, rituals, dances, songs, recitations, and prayers as complex, abstract, and esoteric as any in the world." The Hopi identity centers on this belief system. Waters explained their devotion, writing, "The Hopis . . . have never faltered in the belief that their secular pattern of existence must be predicated upon the religious, the universal plan of Creation. They are still faithful to their own premise." The Pages stated in 1982 that 95 percent of the Hopi people continue to adhere to these beliefs.

According to oral tradition, the Hopis originated in the First of four worlds, not as people but as fractious, insect-like creatures. Displeased with these creatures' grasp of the meaning of life, the Creator, the Sun spirit Tawa, sent Spider Woman, another spirit, to guide them on an evolutionary migration. By the time they reached the Third

Polingaysi Qoyawayma, No Turning Back: A True Account of a Hopi Girl's Struggle,(University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1964)."S he knew it was the duty of the youngest member of a Hopi family to feed the family gods and she was the youngest present, but she was in a hurry to be off and would have neglected the duty had not her grandmother reminded her."

World, they had become people. They reached the Fourth, or Upper, World by climbing up from the underworld through a hollow reed. Upon reaching this world, they were given four stone tablets by Masaw, the world's guardian spirit. Masaw described the migrations they were to take to the ends of the land in each of the four directions and how they would identify the place where they were intended to finally settle. And so the migrations began, some of the clans starting out in each direction. Their routes would eventually form a cross, the center of which was the Center of the Universe, their intended permanent home. This story of the Hopi Creation holds that their completed journeys finally led them to the plateau that lies between the Colorado and Rio Grande Rivers, in the Four Corners region. As Waters explained, "the Hopi . . . know that they were led here so that they would have to depend upon the scanty rainfall which they must evoke with their power and prayer," preserving their faith in the Creator who brought them to this place. The Hopis are thus connected to their land with its agricultural cycles and the constant quest for rainfall in a deeply religious way.

Employment and Economic Traditions

For more than 3,000 years the Hopis have been farmers in an arid desert climate, dry farming in washes as well as constructing irrigated terraces on the mesas, and supplementing their subsistence economy with small game hunting. Farm and garden plots have traditionally belonged to the women of each clan.

The federal government attempted to subdivide the Hopi reservation in 1910, assigning small parcels to individual Hopi. But the effort failed, and the reservation remained intact. Congress passed the Navajo-Hopi Long Range Rehabilitation Act in 1951, allocating approximately $90 million to improve reservation roads, schools, utilities, and health facilities. In 1966 the Hopi tribal council signed a lease with Peabody Coal Company to strip mine a 25,000 acre area in the Navajo-Hopi Joint Use Area. Traditionalists attempted to block the mining through the federal courts but failed; the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1998, the Hopis won a $6 million judgment that ordered the Navajo to share with the Hopi taxes collected from the Peabody coal mining operation in the Joint Use Area. That same year the Hopis signed an agreement with the federal government for almost $3 million of water and wastewater construction for the villages of First Mesa.

By the 1970s, farming income was declining and wage labor was gaining importance in the Hopi economy. An undergarment factory was established in Winslow, Arizona, in partnership with the Hopis in 1971 but failed in only a few years. By the late twentieth century, the Hopis had a diverse economy of small-scale farming and livestock grazing, various small businesses, mineral development royalty payments, government subsidies for community improvements, and wage-labor incomes. Many traditional Hopi objects were transformed from utilitarian and sacred items to works of art. Commercial art includes the making of kachina dolls, silver jewelry, woven baskets, and pottery. Cooperative marketing organizations and various enterprises for Hopi craftspeople, including Hopicrafts and Artist Hopid, are available on-reservation and off. In addition to arts and crafts shops, small businesses on-reservation include two motels, a museum, and several dining facilities and gas stations.

Politics and Government

The Hopis have always been organized according to a matrilineal clan system, which in the late 1990s

The Hopis, protecting their sovereignty, never signed a treaty with the U.S. government. The Hopi Tribal Council and government was established in 1935 with a written constitution but disbanded in 1943. The government was reestablished in 1950, and the nation received federal recognition again in 1955, making available a range of social services and funding opportunities. With coal, natural gas, oil and uranium minerals resources, the Hopis are members of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes. Founded in 1975, the council speaks with a unified Native American voice to the federal government on mineral exploration and development policies and provides technical information to the member tribes.

Individual and Group Contributions

ACADEMIA

Don C. Talayesva (b.1890) was born on the Hopi reservation in Oraibi and was raised in the traditional Hopi Way for the early part of his life. After attending the Sherman School for Indians in Riverside, California, Talayesva returned to the reservation to resume the traditional Hopi way of life. He became the subject of study by anthropologist Leo Simmons in 1938, which led to the noted 1942 publication Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian, which has remained a popular account of Hopi life.

Elizabeth Q. White (c.1892–1990), also known as Polingaysi Qoyawayma, was born at the traditional village of Old Oraibi. She graduated from Bethel College in Newton, Kansas, after studying to become a Mennonite missionary at the Hopi reservation. She became a teacher in the Indian Service on the reservation, where she became a noted educator, eventually earning the U.S. Department of Interior's Distinguished Service Award. White wrote several books on Hopi traditional life and founded the Hopi Student Scholarship Fund at Northern Arizona University.

ART

Traditional Hopi anonymity changed in the twentieth century as many individuals began to be recognized for their work. Nampeyo (1859–1942), born in Hano on First Mesa, helped revive Hopi arts by reintroducing ancient forms and designs she had noted in archaeological remains into her pottery. Her work became uniquely artistic. Nampeyo was used in promotional photographs by the Santa Fe Railway and others, and her pots were added to the collection of the National Museum in Washington, D.C. Nampeyo's daughters and granddaughter, Hooee Daisy Nampeyo (b.1910) carried on her artistry in ceramics. Her granddaughter Hooee also grew up in Hano, learning ceramics from her grandmother. She furthered Hopi and Zuni art in the Southwest, working in ceramics and silver.

Born at the traditional village of Shongopavi at Second Mesa, Fred Kabotie (1900-1986) attended the Santa Fe Indian School as a teenager, where his talent for painting was recognized. Kabotie became noted especially for his depictions of kachinas, which vividly portrayed supernatural powers. In 1922, Kabotie won the first annual Rose Dugan art prize of the Museum of New Mexico, and by 1930 his paintings were on permanent exhibit in the museum. Kabotie went on to become internationally recognized and his work was exhibited at such major museums as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. His work toured internationally in Europe and Asia. He received a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship in 1945, and he was elected to the French Academy of Arts in 1954. In the 1940s, Kabotie founded the Hopi Silvercraft Cooperative Guild, teaching unemployed World War II veterans the art of silverworking. Charles Loloma was a noted student. From 1937 to 1959, he taught art back home in Oraibi, Arizona furthering a tribal artistic tradition. In 1958, Kabotie was awarded the U.S. Indian Arts and Crafts Board's Certificate of Merit. His son, Michael, co-founded Artist Hopid to promote Hopi artists.

Charles Loloma's (1921–1991) jewelry is among the most distinctive in the world. The originality of his designs stems from the combination of nontraditional materials, such as gold and diamonds, with typical Indian materials such as turquoise. He also received great recognition as a potter, silversmith, and designer. Loloma was born in Hotevilla on the Hopi reservation and attended the Hopi High School in Oraibi and the Phoenix Indian High School in Phoenix, Arizona. In 1939 Loloma painted the murals for the Federal Building on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, as part of the Golden Gate International Exposition. The following year, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board commissioned him to paint the murals for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1940, Loloma was drafted into the army, where he spent four years working as a camouflage expert in the Aleutian Islands off the Alaskan coast. After his discharge, he attended the School for American Craftsmen at Alfred University in New York, a well-known center for ceramic arts. This choice was unprecedented on Loloma's part, since ceramics was traditionally a woman's art among the Hopis. After receiving a 1949 Whitney Foundation Fellowship to study the clays of the Hopi area, he and his wife, Otellie, worked out of the newly opened Kiva Craft Center in Scottsdale, Arizona. From 1954 to 1958 he taught at Arizona State University, and in 1962 he became head of the Plastic Arts and Sales Departments at the newly established Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In 1963 Loloma's work was exhibited in Paris. After 1965, Loloma spent the rest of his years on the Hopi reservation, where he continued working and teaching his art to several apprentices. By the mid-1970s, his jewelry had been exhibited throughout the country and in Europe, and his pieces had won numerous first prizes in arts competitions. Loloma was one of the first prominent Indian craftsmen who had a widely recognized unique personal style.

Otellie Loloma (1922–1992), born at Shipaulovi on Second Mesa, received a three-year scholarship to the School of the American Craftsmen at Alfred University in New York, where she specialized in ceramics. At Alfred she met and later married Charles Loloma, an internationally famous Hopi artist. Otellie herself received world acclaim for her ceramics and was considered the most influential Indian woman in ceramics. Loloma taught at Arizona State University, at the Southwest Indian Art Project at the University of Arizona, and at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). She also performed traditional dance, performing at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico and at a White House special program. Her work has been internationally shown and is exhibited at a number of museums, including the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, the Heard Museum, and Blair House in Washington, D.C. One of her last awards was an Outstanding Achievement in the Visual Arts award from the 1991 National Women's Caucus for Art.

EDUCATION

Eugene Sekaquaptewa (1925– ) was born on the Hopi reservation at Hotevilla. He earned an M.A. from Arizona State University before joining the U.S. Marines in 1941. He survived the U.S. invasion of Iwo Jima and other intense battles. Sekaquaptewa returned to Arizona State University to teach education courses and participate in the university's Indian Community Action Project, in addition to teaching at the Indian boarding school in Riverside, California, the Sherman Institute. He has published a number of professional papers on Hopi education.

FILM, TELEVISION, AND THEATER

Actor Anthony Nukema was of Hopi and California Karok ancestry, and appeared in Pony Soldier (1952) and Westward Ho the Wagons! (1957). As independent filmmakers documenting experiences of the native peoples of the Southwest, Maggi Banner produced Coyote Goes Underground (1989) and Tiwa Tales (1991). The prolific Victor Masayesva Jr. produced Hopiit (1982), Itam Hakim Hopiit (1984), Siskyavi: A Place of Chasms (1991), and Imagining Indians (1992) among others.

JOURNALISM

An influential periodical publisher and editor, Rose Robinson (1932– ) was born in Winslow, Arizona and earned degrees from the Haskell Institute and the American University in Washington, D.C. in journalism studies. Robinson was a founding board member of the American Indian Press Association (later renamed Native American Journalist Association) before becoming its executive director. She also served as a member of the U.S. Department of the Interior's Indian Arts and Crafts Board, as information officer for the Bureau of Indian Affairs' Office of Public Instruction, as vice president and director of the Phelps-Stokes Fund's American Indian Program, and in various leadership roles with the North American Indian Women's Association. Robinson guides publication of periodicals for the Native American–Philanthropic News Service, including The Exchange and The Roundup. In 1980 she received the Indian Media Woman of the Year award.

LITERATURE

Poet Wendy Rose (1948– ) was born Bronwen Elizabeth Edwards in Oakland, California and grew up in the San Francisco area. She studied at Contra Costa College and earned an M.A. in anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley. Some early work was published under the name Chiron Khanshendel. Her work, which focuses on modern urban Indian issues, has been included in numerous anthologies, in feminist collections such as In Her Own Image (1980) and more general collections, including Women Poets of the World (1983), in addition to her own published collections, Hopi Roadrunner Dancing (1973), Lost Copper (1980), What Happened When the Hopi Hit New York (1982), The Halfbreed Chronicles and Other Poems (1985), Now Poof She Is Gone (1994), and Bone Dance: New and Selected Poems, 1965–1993 (1994). Rose has also served as editor for the scholarly journal American Indian Quarterly and has taught at Fresno City College, where she was director of the American Indian Studies Program.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Al Qoyawayma (c.1938– ) became a prominent Hopi engineer as well as a noted ceramic artist. Born in Los Angeles, he earned an M.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of California at Berkeley in 1966. Working for Litton Systems, Inc., Qoyawayma developed high-tech airborne guidance systems. He moved to Arizona, becoming manager for environmental services for the Salt River Project. As an understudy of his aunt, Polingaysi Qoyawayma (Elizabeth White), he has also become an accomplished ceramicist, with his works displayed at the Smithsonian Institute and the Kennedy Art Center in Washington, D.C.

A geneticist and the first Hopi to receive a doctorate in sciences, Frank C. Dukapoo (1943– ) founded the National Native American Honor Society in 1982. Duckapoo, born on the Mohave Indian reservation in Arizona, has specialized in investigating factors contributing to birth defects in Indians, among other research topics. He is also an accomplished saxophone player. Duckapoo earned his Ph.D. from Arizona State University and has taught at Arizona State, San Diego State University, Palomar Junior College, and Northern State University. Besides holding an executive position with the National Science Foundation from 1976 to 1979, he was also director of Indian Education at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona, and executive secretary for the National Cancer Institute.

SPORTS

Louis Tewanima (1879–1969) was not only the teammate of the famous American Indian athlete Jim Thorpe, but a world-class athlete in his own right. Born at Shongopovi, Second Mesa, on the Hopi Indian reservation, Tewanima chased jackrabbits as a boy. He was on the track team of the famous Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania under legendary coach Glenn "Pop" Warner. Tewanima established world records in long-distance running. At one track meet, Tewanima, Jim Thorpe, and Frank Mount Pleasant of Carlisle beat 20 athletes from Lafayette College. The U.S. Olympic Team selected Tewanima and Thorpe without requiring them to undergo trials—a rare honor. In 1912 they sailed to Stockholm, where they became U.S. heroes. Thorpe was proclaimed "the greatest athlete in the world" by the king of Sweden, and Tewanima won a silver medal in the 10,000 meter race. His performance set a U.S. record that lasted more than 50 years, until Billy Mills, a Sioux distance runner, surpassed it in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Tewanima returned home to Second Mesa, where he tended sheep and raised crops. Just for fun, to watch the trains go by, he would run to Winslow, Arizona, 80 miles away. In 1954, he was named to the All-Time United States Olympic Track and Field Team and in 1957 was the first person inducted, to a standing ovation, into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame at a dinner given in his honor. The Tewanima Foot Race is run every September at Kykotsmovi. The tribe established a 2002 Winter Olympic Committee to mark a return of the Hopis to the Olympics and showcase Hopi arts and crafts.

VISUAL ARTS

Weaver Ramona Sakiestewa (1949– ) was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to a Hopi father. She attended New York's School of Visual Arts and specialized in the treadle loom. Sakiestewa combines ancient design elements with contemporary weaving techniques, establishing a unique tradition in Native American arts. She co-founded ATLATL, a national Native American arts organization. Her tapestries have been shown at various shows and galleries including the Heard Museum of Phoenix and the Wheelwright Museum of American Indian in Santa Fe.

Award-winning artist and teacher Linda Lomahaftewa (1947– ) was born in Phoenix, Arizona. She attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe and earned an M.A. in fine arts in 1971 from the San Francisco Art Institute. Lomahaftewa's drawings and paintings reflecting Hopi spirituality and storytelling have been exhibited throughout the United States. She has received numerous awards and has taught at various colleges and universities, including University of California at Berkeley and back at the Institute.

Media

The surrounding Navajo reservation established Navajo Communications, which provides various telecommunications services. However, the Hopis have no comparable utility and remained unconnected to the Navajo system.

Tutu-Veh-Ni.

A biweekly newsletter published by the Hopi Office of Public Relations.

Address: P.O. Box 123, Kykotsmovi, Arizona 86039.

Telephone: (602) 734-2441.

Organizations and Associations

Hopi Cultural Center.

Opened in 1970, the on-reservation facility houses various collections of Hopi arts and crafts and the Hononi Crafts shop.

Address: P.O. Box 67, Second Mesa, Arizona 86043.

Telephone: (602) 734-2401.

The Hopi Foundation.

The nongovernmental Foundation is based on Third Mesa, promoting cultural preservation led by Hopi professionals and laypersons.

Address: P.O. Box 705, Hotevilla, Arizona 86030.

Silvercraft Cooperative Guild.

Supports and sponsors Hopi artists.

Address: Box 37, Second Mesa, Arizona 86043.

Telephone: (602) 734-2463.

Museums and Research Centers

Hopi Cultural Preservation Office.

Established in 1989 to implement a 1987 tribal historic preservation plan protecting important Hopi sacred and cultural sites, including traditional subsistence gathering areas.

Contact: Leigh Kuwanwisiwma.

Address: 123 Kykotsmovi, Arizona 86039.

Telephone: (520) 734-2244.

Hopi Tribal Museum.

Address: P.O. Box 7, Second Mesa, Arizona 86035.

Telephone: (602) 234-6650.

Museum of Northern Arizona.

Hosts the Hopi and Navajo Arts and Crafts Show annually in June and July.

Address: Route 4, Box 720, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001.

Telephone: (602) 774-5211.

Sources for Additional Study

Benedek, Emily. The Wind Won't Know Me: A History of the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute. New York: Knopf, 1992.

Leitch, Barbara A. A Concise Dictionary of Indian Tribes of North America. Algonac, MI: Reference Publications, 1979.

Loftin, John D. Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Page, Susanne and Jake. Hopi. New York: Harry Abrams, 1994.

Parsons, Elsie Clews. Hopi and Zuñi Ceremonialism. New York: Harper and Bros., 1950. Reprint. Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint, 1976.

Waters, Frank. Book of the Hopi. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

First i would like to inform you that my English are not that good so i hope you will understand my possible grammar mistakes i might make! I am 27 years old from Greece and i am not an archaeologist or a historian. Latetly i read some books about the history of the ancient civilizations in North and South America and i found information that i couldn't imagine. I read about Mayas and Aztecs, native Indians tribes and many more. This how i end up here, in Hopis tribe.

I found Hopis as a very interesting source of information, but i have also found something that really made me feel curious about the connection between the civilizations.

The "Sacret book" of Hopis as well as the "Popol Voux" of the indians of Guatemala refer to a connection with another civilation. Particularly, they both write about some white visitors Gods with beards coming with their "pae = ships" from there that the sun was rising (Hila Tiki).

The "Sacret book" of Hopis also refer to a huge cataclysm where their great God Soticnag (sorry if i don't write the names correctly in English) ordered the woman with the peplum (veil) to save some humen from the great upcoming disaster by putting them to the highest place on earth.

In ancient Greece, in Athens, young women where weaving a peplum for Goddess Athina in order to celebrate the Panathinaia feast. Is there any possible connection between these two stories?

The Hopis also believed that the earth was round and not flat, and they survived from three great cataclysms. The ancient Greeks believed the same things too. Isn't that weird?

I believe that as long as you search deep into some civilizations, you find some common things between them. I mentioned some of the common facts that i found during my little research. I also found many more connections between Eastern and Western civilizations way before Christopher Colombus arrived in the shores of America in 1492.

I also believe that Henriette Mertz's research would let you understand more of what i am talking about.

Thank you for spending your time reading my comment and if you agree or disagree with some of things i wrote i would be honored to have your kind reply.

etc.

How do these system interact to influence the way of The hopis?

Thank you. Your article is wonderful!

I have some questions for a school Projekt and I wonder if you could answer them for me.

1. Where did they live?

2. How did they live?

3. Were they forced to leave their land?

4. Where and how do they live today?

5. What is special about their culture?

6. Famous people?

Thank you if you answer (some of) them!!