Finnish americans

by Marianne Wargelin

Overview

Finland, a nation-state created in the closing days of World War I, is located in the far northern reaches of Europe. It is bounded by Sweden to the west, Russia to the east, Norway to the north, and the Gulf of Finland to the south. About 90 percent of Finns are Lutheran; the Russian Orthodox church (two percent) is the second largest in the nation. Finnish people continue to maintain a unique language spoken today by only about 23 million people worldwide.

The nearly five million people of contemporary Finland reflect the traditional groups who settled in the nation centuries ago. The largest group consists of Finns who speak Finnish; the second largest group, some six percent, are Finland-Swedes (also known as Swede Finns) who speak Swedish; the most visible minority groups are the Sami (about 4,400), who speak Sami (or Lappish) and live in the North, and the Gypsies (about 5,500), who live in the South.

HISTORY

The ancestors of these peoples came under the domination of the Swedes in the twelfth century, when Finland became a province of Sweden. While the Swedish provinces operated quite independently for a time, efforts to centralize power in the kingdom in the sixteenth century made Finns citizens of Sweden. Sweden was the primary power in the Baltic region for more than a hundred years, until challenged by Russia in the eighteenth century. By 1809 Sweden was so weakened that she was forced to cede her entire Baltic holdings, including Finland, to Russia.

Russia gave Finland a special status as a "Grand Duchy," with the right to maintain the Lutheran religion, the Finnish language, and Finnish constitutional laws. This new status encouraged its leaders to promote a sense of Finnish spirit. Historically a farming nation, Finland did not begin to industrialize until the 1860s, later than their Nordic neighbors; textile mills, forestry, and metal work became the mainstays of the economy. Then, in the final days of the nineteenth century, Russia started a policy of "Russification" in the region, and a period of oppression began.

Political unrest dominated the opening years of the twentieth century. Finland conducted a General Strike in 1906, and the Russian czar was forced to make various concessions, including universal suffrage—making Finland the first European nation to grant women the right to vote—and the right to maintain Finland's own parliament. The oppressive conditions returned two years later, but Finland remained a part of Russia until declaring its own independence in the midst of the Russian Revolution of 1917. A bitter civil war broke out in Finland as the newly independent nation struggled between the philosophies of the bourgeois conservatives and the working class Social Democrats. In 1919 the nation began to govern itself under its own constitution and bill of rights.

MODERN ERA

With basic democratic rights and privileges established, the 1920s and 1930s emerged as a period of political conservatism and right wing nationalism. Then, in 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland. War between the two nations ensued—first in a war known as the Winter War, then in the so-called Continuation War. When it ended, Finland made major concessions to the Soviets, including the loss of a considerable portion of its eastern territory.

In the 1950s Finland continued its transformation from a predominantly agricultural economy into a modern industrial economy. By the 1960s it had established itself as a major design center in Europe, and by the end of the 1970s it maintained a post-industrial age culture with a stable economy that continued to produce premier quality work in the arts. Throughout the rest of the twentieth century, Finland maintained a strict policy of neutrality towards its neighbors to the east and west.

THE FIRST FINNS IN AMERICA

The first Finns in North America came as colonists to New Sweden, a colony founded along the Delaware River in 1638. The colony was abandoned to the Dutch in 1664, but the Finns remained, working the forest in a slash-and-burn-style settlement pattern. By the end of the eighteenth century, their descendants had disappeared into a blur amidst the dominant English and Dutch colonist groups. However, many Finnish Americans believe that a descendant of those Finnish pioneers, John Morton, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Few material signs—other than their distinctive log cabin design and place names—remain to mark their early presence.

A second colonial effort involved Finns in the Russian fur trading industry. In Sitka, Alaska, Finns mixed with Russian settlers in the 1840s and 1850s, working primarily as carpenters and other skilled craftsmen. Two of Alaska's governors were Finnish: Arvid Adolph Etholen (1799-1876) served from 1840 to 1845, and Johan H. Furuhjelm (1821-1909) served from 1859 to 1864. A Finnish pastor, Uno Cygnaeus (1810-1888), who later returned to Finland to establish the Finnish public school system, also served the Finnish American community. Today, this Finnish presence is represented in the Sitka Lutheran church, which dates from that period. After 1867, when Alaska was transferred to the United States, some of the Sitka Finns moved down to communities developing along the northwest coastline—places like Seattle and San Francisco.

Colonial settlers were small in number. Similarly, according to Reino Kero in Migration from Finland to North America in the Years Between the United States Civil War and the First World War, the Finnish sailors and sea captains who left their ships to enter the California Gold Rush or to establish new lives in American harbor cities like Baltimore, Galveston, San Francisco, and New York, numbered only several hundred. One sailor, Charles Linn (Carl Sjodahl; 1814-1883), became a wealthy southern merchant who ran a large wholesale business in New Orleans and later established Alabama's National Bank of Birmingham and the Linn Iron Works. He is credited with opening the immigration from southern Finland to the United States when, in 1869, he brought 53 immigrants from Helsinki and Uusimaa to work for his company.

SIGNIFICANT IMMIGRATION WAVES

Finnish immigration is considered to have occurred primarily between 1864 and 1924. Early Finnish immigrants to the United States were familiar with agricultural work and unskilled labor and were therefore new to industrial work and urban life. Later, skilled workers like carpenters, painters, tailors, and jewelers journeyed to the States, but the number of professionals who immigrated remained small until after 1965. Most scholars have estimated that, at the most, some 300,000 Finnish immigrants remained to become permanent residents and citizens of the United States of America. Of these, about 35,000 were Finland Swedes and about 15,000 Sami.

The first immigrants arrived in 1864, when Finns from northern Finland and Norway settled on homestead prairie lands in south central Minnesota. The next year 30 Finnish miners living in Norway went to work in the copper mines in Hancock, Michigan. These Finns, originally from northern Finland, developed the first permanent Finnish American communities in the American Midwest. Continued economic depression in Finland encouraged others to leave their homeland; the number of immigrants grew to 21,000 before 1887.

Those from northern Norway and Finland who traveled as family groups were part of the Great Laestadian Migration of 1864-1895, a migration that began shortly after the death of founder Lars Levi Laestadius (1800-1861). Looking for ways to maintain a separatist lifestyle as well as to improve their economic standing, Laestadian families began a migration that has continued in some form to the present day. Finnish American Laestadian communities formed in the mining region of Michigan and in the homestead lands of western Minnesota, South Dakota, Oregon, and Washington. These Laestadians provided a sense of community stability to the additional immigrants, single men who had left their families in Finland and who migrated from job to job in America. Some of these men returned to Finland; others eventually sent for their families.

After 1892 migration shifted from northern to southern Finland. Most emigrants from this phase were single and under the age of 30; women made up as much as 41.5 percent of the total. A very large increase in the birthrate after 1875 added to the pool of laborers who left home to work in Finland's growing industrial communities. This wave of internal migration to the city foreshadowed an exodus from Finland. "Russification" and a conscription for the draft added even further to the numbers after 1898.

Twentieth-century emigration from Finland is divided into three periods: before the General Strike; after the General Strike and before World War I; and between World War I and the passage of the Immigration Restriction Act. Before the General Strike, the immigrants who settled in the States were more likely to be influenced by the concepts of Social Democracy. After the General Strike, the immigrants were largely influenced by the use of direct force rather than political action to resolve social problems. Immigrants after World War I—now radicalized and disenchanted from the experience of the bloody civil war—brought a new sense of urgency about the progress of socialism.

Two immigration periods have occurred since the 1940s. After World War II, a new wave of immigration, smaller but more intense, revitalized many Finnish American communities. These Finns were far more nationalistic and politically conservative than earlier immigrants. A more recent wave of immigration occurred in the 1970s and 1980s, as young English-speaking professionals came from Finland to work in high-tech American corporations.

SETTLEMENT

Finnish American communities cluster in three regions across the northern tier of the United States: the East, Midwest, and West. Within these regions, Finland Swedes settled in concentrations in Massachusetts, New York City, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, and California. Sami peoples settled predominantly in Michigan, Minnesota, the Dakotas, Oregon, and Washington.

The 1990 U.S. Census Bureau report confirms that these regions still exist for the 658,870 Americans who claim Finnish ancestry. The five states with the largest populations are Michigan, with 109,357 (1.2 percent of the total state population); Minnesota, with 103,602 (2.4 percent); California, with 64,302 (.02 percent); Washington, with 44,110 (0.9 percent); and Massachusetts (0.5 percent). Half of all Finnish Americans—310,855—live in the Midwest, while 178,846 live in the West. Three further regions—the southeastern United States (Florida and Georgia), Texas, and the Southwest (New Mexico and Arizona)—have developed as retirement communities and as bases for Finnish businesses selling their products to an American market.

Reverse immigration occurred both in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the nineteenth century, many men came without families and worked for a while in mining (especially copper and iron ore mining) and lumber, in fishing and canning, in stone quarries and textile mills, and on railroads and docks; they then returned to the homeland. Others came and worked as domestics, returning to Finland to retire. The most significant reverse immigration occurred in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when 10,000 Finnish American immigrant radicals and their families sold all their belongings and left to settle in the Finnish areas of the Soviet Union. They took their dreams of creating a workers' paradise with them, as well as solid American currency, American tools, and technical skills. Today, reverse migration occurs primarily among the Laestadians who may marry and move to Finland.

Like the Swedes and Norwegians, Finns in America were tolerated and accepted into the communities of "established" Americans during the first wave of mass immigration. Their early competitors for work in the mines were the Irish and the Cornish, two groups with whom they had ongoing strained relations.

Finnish Americans soon developed a reputation for clannishness and hard work. Work crews of strictly Finnish laborers were formed. As documented in Women Who Dared, Finnish domestics were always sought after because they worked so hard and excelled at cooking and homemaking. Reputations for good and hard work were tarnished, however, when the second wave of immigrants began to organize themselves and others to fight poor wages and working conditions. Finns became known as troublemakers for organizing strikes and leading protests. They were blacklisted and efforts were made to deport them. Racist slurs—epithets like "Finn-LAND-er" and "dumb Finn"—developed, and some Finns became victims of violent vigilantism. Specific efforts to single them out from other working-class immigrants as anti-American put them on the front pages of local, regional, and national newspapers.

By the end of the twentieth century, Finnish Americans had essentially become invisible. They worked hard to be indistinguishable from other Euroamericans and, as descendants of white Europeans, fit easily into the mass culture. Many do not visibly identify with any part of their heritage.

Key issues facing Finnish Americans in the future relate to their position as a culture on the margin. Recent generations seem to be drawn more strongly to America's hegemonic culture and therefore continue to move away from their unique heritage.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Finnish Americans themselves are a multicultural society. Being a part of the Laestadian, Finland-Swede, or Sami minorities is different than being part of the Finnish American hegemony. Early Finnish Americans had a reputation for being clannish. Reported by sociologists studying Finns in the 1920s and 1930s, this impression was echoed by citizens who lived beside them. Reenforcing this belief was their unusual language, spoken by few others anywhere. Finnish immigrant children, who spoke their native language in the grade schools of America, were marked as different; Finnish was difficult for English speakers to learn to use, a fact that encouraged American employers to organize teams of "Finnish-only" workers. And the "sauna ritual," an unheard of activity for Anglo-Americans, further promoted a sense that Finns were both exotic and separatist.

Once in the United States, Finnish immigrants recreated Finnish institutions, including churches, temperance societies, workers' halls, benefit societies, and cooperatives. Within those institutions, they organized a broad spectrum of activities for themselves: weekly and festival programs, dances, worship services, theater productions, concerts, sports competitions, and summer festivals. They created lending libraries, bands, choirs, self-education study groups, and drama groups. Furthermore, they kept in touch with each other through the newspapers that they published—over 120 different papers since the first, Amerikan Suomalainen Lehti, which appeared for 14 issues in 1876.

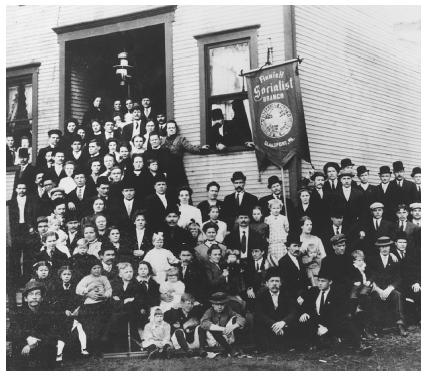

Finnish immigrants used these recreated Finnish institutions to confront and ease their entrance into American culture. The activities helped them assimilate. For example, Finnish American socialists created their own Socialist Federation that functioned to organize Finns; then, the federation itself joined the Socialist Party of America's foreign-language section, which then connected them with the struggle for socialist ideas and actions being promoted by "established" Americans. In a similar manner, the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church in America wrote their Sunday school readers in Finnish, yet used the reader to teach American citizenship and history, including stories of American role models like Abraham Lincoln, together with Finnish cultural heroes.

To help maintain their own identities in America, early Finnish immigrants also developed at least two institutions that had no counterpart in Finland. The first was a masonic-type lodge called the Knights of Kaleva, founded in 1898, with secret rituals based on the ancient Finnish epic The Kalevala. (A women's section called the Ladies of Kaleva followed in 1904.) Local chapters, called a tupa for the knights and a maja for the ladies, provided education in Finnish culture, both for the immigrants and for the larger "established" American community. The second institution, directed toward the immigrants' children, was based on the American Sunday school movement. Both the Church Finns and the Hall Finns published materials specifically for use in Sunday schools. They taught their children the ways of Finnish politics and religion in Finnish-language (and later in English-language) Sunday schools and summer camps.

Finnish American businesses and professional services were developed to serve Finnish communities. In big cities like Minneapolis, Detroit, and Chicago, immigrants created Finntowns, while in small cities like Worcester and Fitchburg, Massachusetts, or Astoria, Oregon, they created separate institutions. In some cities—like those on the Iron Range in Minnesota—Finns became the largest foreign-born population group. Finns actually made up more than 75 percent of the population of small towns like Wakefield, Michigan, and Fairport Harbor, Ohio.

The immigrants were quick to adopt American ways. Almost off the boat, young women would discard the triangular cotton scarf ( huivi ) worn over their hair or the heavy woolen shawl wrapped around their bodies and begin to wear the big wide hats and fancy puffed sleeve bodices so popular in the States at the end of the nineteenth century. Men donned bowler hats and stiff starched collars above their suit coats. Those Finnish immigrant women who began their lives in America working as domestics quickly learned to make American style pies and cakes. And the Finns' log cabins, erected on barely cleared cutover lands, were covered with white clapboard siding as soon as finances permitted.

Recent emigrants from Finland have been quick to adopt the latest in American suburban living, becoming models of post-modern American culture. Privately, however, many Finnish Americans maintain the conventions of the homeland: their houses contain the traditional sauna, they eat Finnish foods, they take frequent trips to Finland and instruct their children in the Finnish language, and their social calendar includes Finnish American events. In the process, they bring new blood into Finnish American culture, providing role models for Finnishness and reenergizing Finnish language usage among the third and fourth generations.

MISCONCEPTIONS AND STEREOTYPES

Finnish Americans became the victims of ethnic slurs after socialist-leaning Finnish immigrants began to settle in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. Finnish immigrant promoters of labor activism prompted racist responses directed at all Finnish Americans. The racist response reached its apex in 1908, when "established" Americans turned to the power of federal law, bringing to federal district court the deportation trial of one John Swan, a Finnish immigrant worker. According to Carl Ross in The Finn Factor, the unusual argument that Finns were actually of Mongolian descent—and therefore subject to the Asian Exclusion Act—hit many Finnish Americans hard and polarized the community into two camps, one conservative, identifying itself as "True Finns," and the other socialist, promoting American citizenship to its membership. In spite of efforts on both sides, various vigilante activities continued against Finnish Americans even into the late 1930s, as the 1939 wrecking of the Finn Hall in Aberdeen, Washington, attests. Being called a "Finn-LAND-er" became "fighting words" to both first and second generation Finnish Americans.

Stereotyping hastened Finnish assimilation into the American mainstream. As white Europeans, they could do just that. Some Finnish Americans anglicized their names and joined American churches and clubs. Others, identifying themselves as indelibly connected to America's racial minorities, entered into marriages with Native Americans, creating a group of people known in Minnesota and Michigan as "Finndians."

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

In this drive to assimilate, Finnish customs that could remain invisible to the outside world were maintained in the States. Such diverse activities as berry picking, hunting, trapping, woodworking, knitting, and weaving can all be traced to the homeland. And many Finns in America have not lost their love for the sauna.

Today, the institutions of the immigrants are, for the most part, gone. For example, except for the Laestadians, few Finnish Lutheran churches offer a glimpse into the rituals of the Church of Finland. Yet an identifiable Finnish American culture remains. Beginning in the 1950s, older institutions began to be replaced by a Finnish American club movement, which includes such organizations as the Finlandia Foundation, the Finnish American Club, and the Finnish American Historical Society. Some organizations from the former days, like the Saima Society of Fitchburg and the Knights of Kaleva in Red Lodge, Montana, have been recycled to serve a new generation's club needs. Meanwhile, large Finnish American populations like the one in greater Detroit have created a new Finn Hall tradition that unifies all the various political and religious traditions.

FinnFest USA and Salolampi Language Village further strengthen Finnish traditions and customs in the States. An annual national summer festival, FinnFest USA, founded in 1983, brings Finnish Americans from all political and religious camps together for three days of seminars, lectures, concerts, sports events, dances, and demonstrations. The festival's location revolves each year to a different region of the Finnish American geography. Salolampi, founded in 1978, offers a summer educational program that allows young people to immerse themselves in Finnish language and culture. Part of the Concordia College Language Villages Program in northern Minnesota, the school serves children from throughout the United States.

A Finnish American renaissance has also blossomed. The movement began in the 1960s, when third and fourth generation Finnish Americans looked to their own past for models that could help solve the social crises in America. It expanded to include efforts to define and express themselves as members of a culture of difference. The renaissance, which includes cultural revival and maintenance as well as new culture creativity, has nurtured new networks between Finland and the United States.

Within the new social history movement, the renaissance gave rise to a new generation of scholars and creative writers who focused on Finnish American history. By the 1970s, in response to the folk music movement of a decade earlier, musicians also turned to their Finnish American heritage for inspiration. The renaissance includes the visual arts as well.

While this collective renaissance activity can be found throughout the various regions of Finnish America, its center is in Minnesota, most specifically the Twin Cities, where the University of Minnesota has provided a home at the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) and Finnish Department. The IHRC helped to direct the "Reunion of Sisters Project: 1984-1987," a unique cultural exchange program that brought women and men together from Finland and the United States to consider their common cultural heritage. Then, in 1991, the IHRC co-sponsored the first conference organized to examine this renaissance, a conference entitled "The Making of Finnish America: A Culture in Transition."

CUISINE

The Finnish diet is rich in root vegetables (carrots, beets, potatoes, rutabagas, and turnips) and in fresh berries (blueberries, strawberries, and raspberries in season). Rye breads ( ruisleipa and reiska ) and cardamom seed flavored coffee bread ( pulla or nisu ) are absolute necessities. Dairy products—cheeses, creams, and butters—make the cakes, cookies, pancakes and stews quite rich. Pork roasts, hams, meat stews, and fish—especially salmon, whitefish, herring, and trout, served marinated, smoked, cooked in soups, or baked in the oven—complete the cuisine. At Christmas, many Finnish Americans eat lutefisk (lye-soaked dried cod) and prune-filled tarts. The traditional, meatless Shrove Tuesday meal (the day before Lent) centers on pea soup and rye bread or pancakes. Plainness, simplicity, and an emphasis on natural flavors continue to dominate Finnish and Finnish American cooking even today. Spices, if used, include cinnamon, allspice, cardamom, and ginger. One beverage dominates: coffee (morning coffee, afternoon coffee, evening coffee). "Coffee tables," as the events are called, served with the right assortment of baked goods, are central to both daily life and entertaining.

More recent Finnish immigrants favor foods that gained popularity after World War II—foods often associated with Karelia, the province lost to the Soviets in the Winter War. Among these are karjalan piirakka (an open-faced rye tart filled with potato or rice); uunijuusto (an oven-baked cheese, often called "squeaky cheese"); and pasties, (meat, potato, and carrot or rutabaga pies).

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES

Finnish immigrants who landed on American soil in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as peasants or workers wore heavy woolen stockings, shirts, and skirts. Women wore a triangular scarf, called a huivi, over their heads. However, no traditional clothing was worn for special events and ceremonies. By the 1930s, as Finnish Americans became more affluent, the popularity of Finnish national folk costumes increased. (By this time, members of the middle-class were in a position to travel to Finland to purchase costumes.)

HOLIDAYS

Finnish Americans observe a number of holidays celebrated in Finland. On December 6, many communities commemorate Finnish Independence Day. Christmas parties known as Pikku Joulut are central to the holiday season, just as Laskiainen (sliding down the hill) is celebrated on Shrove Tuesday. Some communities also hold programs in honor of the Finnish epic The Kalevala on Kalevala

Finns in the United States invented St. Urho's Day, a humorous takeoff on St. Patrick's Day, a traditional Irish holiday celebrated on March 17. St. Urho's Day, observed in Finnish American communities each March 16, purportedly commemorates the saint's success in driving the grasshoppers out of Finland.

HEALTH ISSUES

According to some researchers, Finnish Americans are people with a high propensity for heart disease, high cholesterol, strokes, alcoholism, depression, and lactose intolerance.

Many Finnish people believe in natural health care. Immigrants in both the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used such traditional healing methods as massage and cupping (or bloodletting). The sauna is a historic part of healing rituals. When Finns are sick, they take a sauna. Even childbirth was handled by midwives in the sauna. A Finnish proverb, Jos ei sauna ja viina ja terva auta niin se tauti on kuolemaksi, states that if a sauna, whiskey, and tar salve do not make you well, death is imminent. Saunas treat respiratory and circulatory problems, relax stiff muscles, and cure aches and pains. Modern Finnish Americans often turn to chiropractors and acupuncturists for relief of some ailments, but the family sauna remains the place to go whenever one has a cold.

Language

As late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century immigrants, Finns spoke either Finnish or Swedish. Those who spoke Swedish used a form known as Finland-Swedish; those who spoke Finnish used a non-Indo-European language, part of a small language group known as Finno-Ugric. Immigrants to America most likely spoke a regional form of Finnish: most nineteenth-century Finns spoke a northern rural Finnish, while later immigrants spoke a southern rural Finnish. An entirely new language was born in the United States—dubbed "Finglish." Finns arriving in America at the close of the twentieth century tend to speak in a Helsinki dialect.

Assimilation issues often revolved around the maintenance of language. John Wargelin (1881-1970), past president of Suomi College, lost his presidency in 1928 largely because he advocated using English at the college. The Finnish Socialist Federation exploded over orders that they "Americanize" their cultural practices, including their use of Finnish. Various churches vacillated on the language question, most of them finally giving in to using English after World War II. The Laestadians, however, have moved more slowly. Some groups still do all their preaching in Finnish; others use simultaneous translation.

GREETINGS AND OTHER POPULAR EXPRESSIONS

Typical greetings in Finnish include the following: Hyvä paivä ("huv-vaeh pa-e-vaeh")—Good day;

Family and Community Dynamics

Typical family structure among Finnish immigrants was patriarchal. Rural Finnish families were usually large, but in the urban areas, where both husband and wife worked, families often had only one child. Today only the Laestadians continue the tradition of large families.

Since immigrants were separated from their parents and extended families, Finnish American communities developed among immigrants from the same village or region. The 1920 U.S. Census Bureau records indicate that Finnish Americans mostly married other Finnish Americans, both in the first and second generations. By the 1990s, however, Finnish Americans of the third and fourth generations were marrying outside their ethnic group. One exception is the American Laestadian community, whose members prefer courtships within the community and who travel to Finland to meet suitable members of their faith.

EDUCATION

Education is highly valued by Finnish Americans. Even early immigrants were largely literate, and they supported a rich immigrant publishing industry of newspapers, periodicals, and books. Self-education was central. Thus, immigrant institutions developed libraries and debate clubs, and immigrant summer festivals included seminars, concerts, and plays. That tradition continues today in the three-day FinnFest USA festival, which maintains the lecture, seminar, and concert tradition.

In spite of economic hardship, many immigrant children achieved high school and college educations. Two schools were founded by the Finns: the Työväenopisto, or Work Peoples College, in Minnesota (1904-1941), where young people learned trades and politics in an educational environment that duplicated the folk school tradition in Finland; and Suomiopisto, Suomi College, in Hancock, Michigan (1895), which began by duplicating the lyceum tradition of Finland. The only higher education institution founded by Finnish Americans, Suomi provides a Lutheran-centered general liberal arts curriculum to its students. The college continues to honor its Finnish origins by maintaining a Finnish Heritage Center and Finnish American Historical Archives. Suomi started as an academy and added a junior college in 1923 and a four-year college in 1994. The Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (Suomi Synod) established and maintained a seminary there from 1904 to 1958.

Although parochial education never was part of the Finnish tradition, Finnish Americans did develop a program of summer schools and camps where young people learned religion, Finnish culture, politics, and cooperative philosophies. Camps teaching the ideals and practice of cooperativism ran until the late 1950s.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

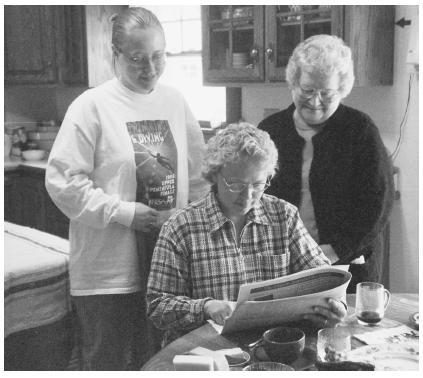

Finnish women have played leading roles in family affairs and community life. In the old country, they ran and organized the household. In addition, immigrant women oversaw the farms while the men found work in the cities, mines, and lumber camps. The women also found daytime employment outside the home, working in laundries and textile manufacturing. In the evenings, they were active in choirs, theaters, politics, and the organization of religious events.

PHILANTHROPY

Finnish Americans practice group-organized philanthropy. Together, they raise barns, build community halls and churches, and do the ritual spring cleaning. Finnish Americans have also supported famine relief in Finland, assisted the Help Finland Movement during the Winter War, and even held a fund-raising drive for microfilming Finnish language newspapers in 1983.

Religion

Over 90 percent of Finnish American immigrants are Lutherans—some more devout than others. Baptized into the church so that their births were recorded, they were also confirmed so that they could marry and be buried—all with official state records.

During the nineteenth century, within the State Church of Finland, four different religious revivals occurred: the Awakenists, the Evangelicals, the Laestadians, and the Prayers movement. These movements operated within the church itself. In addition, socialism—a secular movement with all the fervor of a religion—also developed. During the immigration process, many Finns left the church entirely and participated only in socialist activities. Those who remained religious fell into three separate groups: Laestadians, Lutherans, and free church Protestants.

The Laestadians, who came first, called themselves "Apostolic Lutherans" and began to operate separately in the heady atmosphere of America's free religious environment. However, they could not stay unified and have since divided into five separate church groups. These congregations are led by lay people; ordained ministers trained in seminaries are not common to any of the groups.

In 1898 the Finnish National Evangelical Lutheran church was formed as an expression of the Evangelical movement. The Finland Swedes, excluded from these efforts, gradually formed churches that entered the Augustana Lutheran Synod (a Swedish American church group). In recent years, the Suomi Synod became part of an effort to create a unified Lutheran church in the United States. They were part of a merger that created first the Lutheran Church in America in 1963, and then the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America in 1984.

The Suomi Synod maintained the Church of Finland "divine worship" service tradition and continued the practice of a clergy-led church. However, a new sense of power resting in the hands of the congregation developed, and the church evolved into a highly democratic decision-making institution. Although women were not yet granted the right to be ordained, they were given the right to vote in the affairs of the church in 1909. In addition, they were elected to high leadership positions on local, regional, and national boards. Pastors' wives were known to preach sermons and conduct services whenever the pastor was serving another church within his multiple-congregation assignment. The rather democratic National Synod also granted women the right to vote in the affairs of the congregation. This became an issue when the National Synod merged with the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, which did not allow women to vote.

In addition to Lutherans, Finnish immigrants also organized a variety of free Protestant churches: the Finnish Congregational church (active mainly in New England, the Pacific Northwest, and California), the Finnish Methodist church, the Unitarian church, and the Pentecostal churches.

Employment and Economic Traditions

In the Midwest and the West, early Finnish immigrant men worked as miners, timber workers, railroad workers, fishers, and dock hands. In New England, they worked in quarries, fisheries, and in textile and shoe factories. When single women began to settle in the United States, they went into domestic work as maids, cooks, and housekeepers. In the cutover lands across northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, and in the farmlands of upstate New York and New England, immigrant families left work in industry to raise grain crops and potatoes and run dairy and chicken farms. In the cities, Finnish American immigrants worked in several crafts—as carpenters, painters, tailors, and jewelers.

Later generations who have had the advantage of an American education have chosen professions that expand on the worklife of the immigrants. Men frequently specialize in agriculture-related subjects, such as natural resources management, mining engineering, and geology. A large percentage of women study nursing and home economics, working as both researchers in industry and as public managers in county extension agencies. The fields of education, medical research, the arts, music, and law have also attracted Finnish American students.

Politics and Government

Finnish Americans are a politically active people. As voters in American politics, they overwhelmingly supported the Republican party until the 1930s. After Franklin Delano Roosevelt became president in 1933, Finnish Americans became known as Democratic voters.

Early immigrants emphasized Temperance Societies as a political action force. In 1888 they organized the Suomalainen Kansallis Raittius Veljeysseura (the Finnish National Temperance Brotherhood), which later had as many as 10,000 members. Many immigrants after 1892 had socialist leanings, and itinerant Finnish agitators found many converts in the States. In 1906 the Amerikan Suomalaisten Sosialistiosastojen Järjestö (the Finnish American Socialist Federation) was formed; two years later, the organization became the first foreign-language affiliate within the Socialist Party of America. (Over the next decade, however, the federation began to lose members because of its increasing alignment with the Communist party.)

At the turn of the twentieth century, Finnish Americans worked to change U.S. national policy toward Finland. In 1899 a Finnish American delegation presented a petition to President William McKinley asking for aid to Finland in its fight against czarist Russia. They also lobbied for early recognition of the Finnish Republic and for relief support to the homeland.

Finnish American immigrant women organized feminist-based groups as early as 1895 for the purpose of self-education and the improvement of conditions for women. After 1906—when women in Finland were granted the right to vote—Finnish Americans became heavily involved in American suffrage politics, passing petitions throughout the Finnish American community, participating in suffrage parades, and appearing at rallies. They organized into two wings: one aligned with the temperance movement, which promoted suffrage per se; the other aligned with the socialist movement, which promoted working women's issues. Each published a newspaper, the Naisten Lehti ( Women's Newspaper ), and the Toveritar ( The Working Woman ). Both worked to improve conditions for all American women through political action.

Finns have been very active in union organizing, working often as leaders of strikes that developed in the mining and timber industries. Their workers' halls were centers of union activity and headquarters for strikes, notably in the Copper Country Strike of 1913-1914 and the two Mesabi Range strikes of 1907 and 1916. After World War II, Finnish Americans were central to the organizing of iron miners into the Steelworkers Union on the Marquette Range in Michigan. In addition, Detroit auto workers used the Wilson Avenue Finn Hall to develop their union organizing.

Finns have been elected to political positions, mainly on local and regional levels, serving as postmasters, clerks, sheriffs, and mayors. As of 1995, no Finn had been elected state governor, and only one Finn, O. J. Larson, had been a member of the U.S. Congress. (He was elected to the House in 1920 and again in 1922.) However, Finnish Americans have served in state Houses in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Alaska. Barbara Hannien Linton, who represents a northern Wisconsin district, is one of the most prominent and progressive members of the Democratic Party in the Wisconsin state legislature. The first woman elected to the office of mayor of Ohio—Amy Kaukkonen—was a Finnish

During the effort to win support for U.S. entry into World War I, the administration of President Woodrow Wilson orchestrated a loyalty movement among the Finns. In spite of their anti-draft stance in World War I, Finns have readily served in the U.S. armed forces, beginning with the Civil War, when former Finnish sailors and recent immigrants signed on. Finns served in the Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, and the Spanish Civil War. Finnish American nurses—mostly female—also contributed to the American war effort over the years.

RELATIONS WITH FINLAND

Finnish Americans have long been involved in the political issues of Finland. The American Finnish Aid Committee gathered considerable funds for famine relief in 1902. After the General Strike occurred in 1906, a number of Finnish agitators sought a safe haven in the Finnish American community. After Finland declared itself a republic, Finnish Americans worked with Herbert Hoover to provide food to famine-stricken Finland. Later, they lobbied effectively in Washington, D.C., to get official recognition from the American government for the new nation-state. Their most concerted effort on behalf of the Finns, however, occurred in 1939 and 1940, after the Winter War broke out. They mobilized efforts at such a level, again with Hoover's assistance, that they were able to send $4 million in aid to the war-torn country. Individual family efforts to collect food and clothing for relatives continued well into the end of the decade. In the 1990s Finnish Americans worked actively as volunteers and fund-raisers, promoting religion in the Finnish sections of the former Soviet Union.

Individual and Group Contributions

Finnish Americans as a group tend not to promote the concept of individual merit. ( Oma kehu haisee —a Finnish proverb often quoted by Finnish Americans—means "self-praise smells putrid.") The following sections list contributions made by Finnish Americans:

ART AND ARCHITECTURE

The father and son architectural team of Eliel (1897-1950) and Eero (1910-1961) Saarinen is closely associated with Michigan's Cranbrook Institute, where Finnish design theory and practice were taught to several generations of Americans. Eero Saarinen designed a number of buildings, including the Gateway Arch in St. Louis; the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan; the TWA terminal at New York's Kennedy International Airport; and Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C.

Painters include Elmer Forsberg (1883-1950), longtime professor at the Chicago Institute of Arts and a significant painter in his own right. Religious painter Warner Sallman (1897-1968), a Finland Swede, is most famous for his "Head of Christ," the mass-produced portrait of a Nordic-looking Jesus that became an icon of American Protestantism.

Photojournalist Kosti Ruohomaa, a second generation Finnish American from Maine, created a portfolio of photographs after working more than 20 years for Life and other national magazines. Rudy Autio (1926– ), also a second generation Finnish American, is a fellow of the American Crafts Council whose work is in the permanent collections of major museums. Minnesota-born sculptor Dale Eldred (1934-1993) became head of the Kansas City Institute of Arts and creator of monumental environmental sculptures that are displayed throughout the world.

BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY

The earliest successful Finnish American businessman was Carl Sjodahl (Charles Linn; 1814-1883) who began as a sailor and became a wealthy wholesaler, banker, and industrialist in New Orleans and Birmingham, Alabama. Another early Finnish seaman, Captain Gustave Niebaum (1842-1908), established the Inglenook winery in California.

Vaino Hoover, former president and chief executive officer of Hoover Electric Company, designed and manufactured electric actuators and power flight control system components for aircraft and deep sea equipment. An important figure in the American defense industry of the 1950s and 1960s, he was a member of President Dwight D. Eisenhower's National Defense Advisory Committee. Yrjö Paloheimo (1899-1991) was a philanthropist as well as a rancher in New Mexico and southern California. He organized Help Finland activities in the 1940s, founded a farm and garden school for orphans in Finland in 1947, and established the Finlandia Foundation in 1952. In addition, he and his wife organized the Old Cienaga Village, a living history museum of early Hispanic life in New Mexico. Finnish American Armas Christian Markkula, co-founder of the Apple Computer Co., is listed as one of the 500 richest men in America.

EDUCATION

Finnish Americans in education include Margaret Preska (1938– ). One of the first women in the United States to head an institution of higher learning, she was president of Mankato State University from 1979 to 1992. Robert Ranta (1943– ) is dean of the College of Communication and Fine Arts at the University of Memphis and also serves as a freelance producer of such television specials as the Grammy Awards.

GOVERNMENT

Among the best-known Finnish Americans in government is Emil Hurja (1892-1953), the genius political pollster who orchestrated Franklin Delano Roosevelt's victorious presidential elections. Hurja became a member of the Democratic National Committee during the 1930s. O. J. Larson was a U.S. representative from Minnesota in the early 1920s. Maggie Walz (1861-1927), publisher of the Naisten Lehti ( Women's Newspaper ), represented the Finnish American suffragists in the American suffrage and temperance movements. Viena Pasanen Johnson, co-founder of the Minnesota Farmer Labor Party, was the first woman member of the Minnesota State Teachers' College board of directors. She later became a national leader in the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Gus Hall (1911– ) remains president of the Communist Party of America.

LITERATURE

Jean Auel (1936– ), author of Clan of the Cave Bear and other bestselling novels dealing with prehistoric peoples, is a third generation Finnish American. Less well known but still significant to American letters is Shirley (Waisanen) Schoonover (1936– ), whose Mountain of Winter (1965) has been translated into eighteen languages. Anselm Hollo (1934– ), the renowned translator and writer with more than 19 volumes of verse to her credit, teaches at the Naroba Institute. Pierre DeLattre, author of two novels, Tales of a Dalai Lama, 1971, and Walking on Air, 1980, has been published in some 50 magazines. Recent writers emerging from the small press movement include poet Judy Minty, fiction writer and poet Jane Piirto, and fiction writers Lauri Anderson, Rebecca Cummings, and Timo Koskinen.

MUSIC

Composer Charles Wuorinen (1938– )—the youngest composer to win a Pulitzer Prize—was named a MacArthur fellow in 1986. His music is performed by major symphony orchestras throughout the United States. Tauno Hannikainen was the permanent director of the Duluth Symphony and associate conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Heimo Haitto was a concert violinist who performed as soloist with major philharmonics in Europe and the United States. Legendary virtuoso accordionist Viola Turpinen (1909-1958) became a recording artist and professional musician. Jorma Kaukonen (1942– ) played lead guitar for Jefferson Airplane. Elisa Kokkonen, a young emerging solo violinist, performs with major orchestras in the United States and Europe.

RELIGION

Finnish America's major contributor to American Lutheran theology was renowned professor of theology Taisto Kantonen (1900-1993) of Wittenburg University. Melvin Johnson (1939– ), an administrator at the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America headquarters in Chicago, and retired theologian Raymond W. Wargelin are among the most prominent living church leaders of Finnish descent in America.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Olga Lakela, a former professor of biology at the Duluth campus of the University of Minnesota and the author of numerous scientific papers on plant and bird life in Minnesota, had her name inscribed on the Wall of Fame at the 1940 New York World's Fair as one of 630 Americans of foreign birth who contributed to the American way of life. Ilmari Salminen, a research chemist with Eastman Kodak, specialized in color photography. Vernen Suomi, now an emeritus professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was responsible for several inventions currently used in the exploration of outer space. A younger generation of scientists includes Donald Saari (1940– ), a Northwestern University mathematician in astronomy and economics; Markin Makinen (1939– ), a biophysicist at the University of Chicago; and Dennis Maki (1940– ), a medical doctor who serves as an infectious disease specialist in the Medical School at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

SPORTS

Finnish American sports figures have achieved recognition in track, cross country skiing, ski jumping, and ice hockey. The Finnish American Athletic Club was one of the strongest organizations in U.S. track and field competition. U.S. Olympic hockey and ski jumping teams have included Finnish Americans. Midwestern American sports teams in the 1930s were often called "Flying Finns," after legendary Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi, whose tour of the United States during the 1920s caused a sensation among American track and field enthusiasts. Waino Ketonen was world champion middleweight wrestler from 1918 to 1927. Rick Tapani, pitcher for the Minnesota Twins, and sportscaster Dick Engberg are both third generation Finnish Americans.

THEATER AND FILM

Stage actor Alfred Lunt (1892-1977), who teamed with his actress-wife Lynn Fontanne from the 1920s through the 1950s was a second generation Finnish American from Wisconsin; he showed his Finnish pride when he chose Robert Sherwood's poignant There Shall Be No Night as a touring vehicle and a significant way for the duo to present the plight of Finns fighting in the Winter War in Finland. Bruno Maine was scenic art director for Radio City Music Hall, and Sointu Syrjälä was theater designer for several Broadway shows. Movie actor Albert Salmi (1928-1990) began his career in the New York City Finnish immigrant theater, and Maila Nurmi, who once used the stage name Vampira, hosted horror movies on television in the late 1950s in Los Angeles. She also starred in Ed Wood's immortal alien flick Plan 9 from Outer Space, considered by many critics to be the worst movie of all time. Other Finnish American actresses include Jessica Lange (1949– ) and Christine Lahti (1950– ), granddaughter of early Finnish American feminist Augusta Lahti.

Media

Amerikan Uutiset.

A weekly newspaper in Finnish with some English; it has a long tradition of providing a national forum for nonpartisan political and general news from Finnish American communities across the country. Founded in 1932, the paper was later bought by Finland-born entrepreneurs interested in creating a more contemporary Finland news emphasis. It has the largest Finnish American readership in the nation.

Contact: Sakri Viklund, Editor.

Address: P.O. Box 8147, Lantana, Florida 33462.

Telephone: (407) 588-9770.

Fax: (407) 588-3229.

E-mail: amuutiset@aol.com.

Baiki: The North American Sami Journal.

A quarterly journal published since 1991 by descendants of Sami peoples. It explores their own unique heritage.

Contact: Faith Fjeld, Editor.

Address: 3548 14th Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55407.

Telephone: (612) 722-0040.

Fax: (612) 722-3844.

Finnish Americana.

Founded in 1978, this English-language annual journal features creative writing as well as scholarly articles. The journal reflects the growth of a new group of Finnish Americans interested in Finnish American history and culture. Finnish Americana is the major forum for the new generation of Finnish American intellectuals.

Contact: Michael G. Karni, Editor.

Address: P.O. Box 120804, New Brighton, Minnesota 55112.

Telephone: (612) 636-6348.

Fax: (612) 636-0773.

Finnish American Reporter.

A newsprint journal featuring personal essays, Finnish American community news, and brief news articles reprinted from and about Finland. Founded in 1986, this monthly has gradually built itself into the leading publication for readers seeking an American-oriented presentation of Finnish American cultural life. It is published by the Työmies Society, the left-wing political movement of Finnish America.

Contact: Lisbeth Boutang, Editor.

Address: P.O. Box 549, Superior, Wisconsin 54880.

Telephone: (715) 394-4961.

Fax: (715) 392-5029.

New Yorkin Uutiset.

A weekly independent newspaper featuring news from Finland and Finnish American communities. Founded in 1906 as a daily, the paper—written primarily in Finnish with some English articles—is now a weekly. New Yorkin Uutiset takes a nationalistic and politically conservative position on issues.

Contact: Leena Isbom, Editor.

Address: The Finnish Newspaper Co., 4422 Eighth Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11220.

Telephone: (718) 435-0800.

Fax: (718) 871-7230.

Norden News.

A weekly newspaper featuring news from Finland and Finland-Swede American communities. This Swedish-language paper provides the only current information on the Finnland-Swede community in the United States.

Contact: Erik R. Hermans, Editor.

Address: P.O. Box 2143, New York, New York 10185-0018.

Telephone: (212) 753-0880

Fax: (212) 944-0763.

Raivaaja ( Pioneer ).

A weekly newspaper featuring news from Finland and Finnish American communities. Founded in 1905 as a daily, the newspaper provides a voice for Social Democratic Finnish Americans.

Contact: Marita Cauthen, Editor.

Address: P.O. Box 600, Fitchburg, Massachusetts 01420-0600.

Telephone: (508) 343-3822.

Fax: (508) 343-8147.

E-mail: raivaaja@netplus.com.

Työmies/Eteenpäin.

A weekly newspaper of the Finnish American left wing. Published since 1903, it continues to present Finnish American communist views. Readership remains small and largely Finnish-language directed. The newspaper features both news from Finland and news about the United States, written from a politically radical perspective.

Address: P.O. Box 549, Superior, Wisconsin 54880.

Telephone: (715) 394-4961.

Fax: (715) 394-7655.

RADIO

KAXE-FM, Northern Minnesota.

"Finnish Americana and Heritage Show," In Bemidji, 94.7 FM; in Brainerd, 89.5 FM; in Grand Rapids, 91.7 FM. This English-language program—presented the first Sunday of each month—includes Finnish folk and popular music as well as information about Finnish music events in Minnesota.

Address: 1841 East Highway 169, Grand Rapids, Minnesota 55744.

Telephone: (218) 326-1234.

Fax: (218) 326-1235.

E-mail: kaxe@kaxe.org.

KUSF-FM (90.3).

"Voice of Finland," a weekly one-hour program in the Finnish language provides music, news, interviews, and information about Finnish activities occurring in the region.

Address: 2130 Fulton Street, San Francisco, California 94117-1080.

Telephone: (415) 386-5873.

E-mail: kusf@usfca.edu.

Online: http://web.usfca.edu/kusf .

WCAR-AM (1090).

"Finn Focus," a light entertainment program in Finnish provides music, news, notice of local activities and interviews.

Address: 32500 Park Lane, Garden City, Michigan 48135.

Telephone: (313) 525-1111.

Fax: (313) 525-3608.

WLVS-AM (1380).

" Hyvät Uutiset " (Good News), sponsored by the Lake Worth Finnish Pentecostal Congregation, is a weekly half hour broadcast in Finnish featuring religious music and talk. "American Finnish Evening Hour" provides light entertainment, music, and information about happenings in the listening area and in Finland. "Halls of Finland," a program broadcast in Finnish, includes news reports about local events and activities occurring in the United States and in Finland. "Religious Hour" is sponsored by the Apostolic Lutheran church.

Address: 1939 Seventh Avenue North, Lake Worth, Florida 33461-3898.

Telephone: (561) 585-5533.

Fax: (561) 585-0131.

WYMS-FM (88.9).

"Scandinavian Hour," broadcast once a month, this program provides news from Finland and the local region, interviews, and Finnish music. Broadcast in two languages. "Scenes from the Northern Lights" originates in Bloomington, Indiana, and is offered through syndication on National Public Radio (NPR). It features a wide variety of Finnish music (rock, pop, classical, folk, opera).

Address: 5225 West Vliet Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53208.

Telephone: (414) 475-8890.

Fax: (414) 475-8413.

Online: http://www.wyms.org .

TELEVISION

WLUC.

" Suomi Kutsu " (Finland Calling) is telecast weekly on Sundays from 10:00 to 11:00 a.m. The first half hour is a newsmagazine about Finland and Finnish America, featuring interviews, music, news, and video essays. The second half hour is a Finnish language devotional worship service led by area Lutheran clergy.

Address: 177 U.S. Highway 41 East, Negaunee, Michigan 49866.

Telephone: (906)475-4161; or (800) 562-9776.

Fax: (906)475-4824.

E-mail: tv6sales@wluctv6.com.

Online: http://wluctv6.com .

Organizations and Associations

Finlandia Foundation.

Founded in 1952, this national philanthropic organization's mission is to cultivate and strengthen cultural relations between the United States and the Republic of Finland. Finlandia Foundation distributes over $70,000 annually for cultural programs, grants, and scholarships.

Contact: Carl W. Jarvie, President.

Address: 607 Third Avenue, Suite 610, Seattle, Washington 98104.

Telephone: (206) 285-4703.

Fax: (206) 781-2721.

Finnish American League for Democracy (FALD).

Promotes the study of Finnish American history and culture.

Contact: Marita Cauthen, Executive Officer.

Address: P.O. Box 600, 147 Elm Street, Fitchburg, Massachusetts 01420.

Telephone: (508) 343-3822.

International Order of Runeberg.

Promotes the preservation of pan-Scandinavian culture and traditions, with special emphasis on Finland. Conducts student exchange program.

Contact: Deidre Meanley, Secretary.

Address: 1138 Northeast 153rd Avenue, Portland, Oregon 97230.

Telephone: (503) 254-2054.

Fax: (503) 261-9868.

E-mail: dmeanley@worldacess.net.

Museums and Research Centers

Finnish American Historical Archives of the Finnish American Heritage Center, Suomi College.

Features the best collection of materials that predate the twentieth century, as well as modern materials, including records of the Help Finland Movement, the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (Suomi Synod), and the celebration of the 300th anniversary of the Delaware Colony. A small uncataloged and unsystematic collection of material objects has accumulated; parts of this collection are usually on display. A large photograph collection, an oral history collection, and microfilm archives of newspapers and records stored in Finland round out the resources.

Address: 601 Quincy Street, Hancock, Michigan 49930.

Telephone: (906) 487-7347.

Fax: (906) 487-7366.

Finnish-American Historical Society of the West.

People of Finnish ancestry and friends of Finland interested in discovering, collecting, and preserving material to establish and illustrate the history of persons of Finnish descent in the American West. Maintains Lindgren Log Home, a museum of Finnish-American artifacts from the 1920s.

Contact: Roy Schulbach.

Address: P.O. Box 5522, Portland, Oregon 97228-0552.

Telephone: (503) 654-0448.

Fax: (503) 652-0558.

E-mail: finamhsw@telepor.com.

Online: http://www.teleport.com/~finamhsw .

Immigration History Research Center of the University of Minnesota.

This collection—one of the largest available anywhere—is part of a larger collection of 24 late immigration groups. The Finnish section includes materials from the Finnish American radical and cooperative movements, Finnish American theater, and music.

Contact: Joel Wurl, Curator.

Address: 826 Berry Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55114-1076.

Telephone: (612) 627-4208.

Fax: (612) 627-4190.

Online: http://www1.umn.edu/ihrc .

Other archival collections of Finnish American materials are more regional. For example, the Iron Range Research Center in Chisholm, Minnesota, has a rich northern Minnesota collection, and the Finnish Cultural Center at Fitchburg State College in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, has been trying to reconstitute materials from the New England region.

Finnish Americans have not developed any major museums. The most systematically catalogued collection of Finnish American materials can be found at the Michigan State University Museum in East Lansing, Michigan. The Nordic Heritage Museum in Seattle, Washington, includes an interesting display of Finnish culture, collected and organized by the local Finnish American community.

Finnish Americans have preserved their cultural landscape history at two significant sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Hanka Homestead in Arnheim, Michigan, provides an example of a small backwoods farmstead, while the town of Embarrass, Minnesota, is an excellent example of an entire Finnish American farming community.

Sources for Additional Study

Finnish Diasporaii: United States, edited by Michael G. Karni. Toronto: The Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1981.

The Finnish Experience in the Western Great Lakes Region, edited by Michael G. Karni, Matti E. Kaups, and Doublas J. Ollila, Jr. Vammala. Finland: Institute for Migration, Turku, 1972.

The Finns in North America: A Social Symposium, edited by Ralph Jalkanen. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1969.

Hoglund, A. William. Finnish Immigrants in America, 1880-1920. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1960.

Jalkanen, Ralph. The Faith of the Finns: Historical Perspectives on the Finnish Lutheran Church in America. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1972.

Jutikkala, Eino, and Kauko Pirinen. A History of Finland. New York: Dorset Press, 1988.

Ross, Carl. The Finn Factor in American Labor, Culture, and Society. New York Mills, Minnesota: Parta Publishing, 1977.

Sampo: The Magic Mill—A Collection of Finnish American Writing, edited by Aili Jarvenpa and Michael G. Karni. Minneapolis: New Rivers Press, 1989.

Women Who Dared: The History of Finnish American Women, edited by Carl Ross and K. Marianne Wargelin Brown. St. Paul: Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, 1986.

Kristina: "nisu" is a more regional word to assign the coffee bread and if we want to be more precise, it makes reference to a certain subtype (nisu-ukot- pulla in form of man with raisins as buttons- traditionally eaten during Christmas in rural areas) of "pulla". Pulla is more generic term and you can use it to design everything made from the mass (pullataikina). Other subclasses are: korvapuusti (a long roll which is filled traditionally with cinnamon and sugar, although you can fill it with whatever you want, and baked in pieces), voisilmäpulla ( a pulla in form of a traditional bun with a small hole in the middle where you put a little bit of butter before baking it), bostonpulla (a collection of korvapuusti in a form of a circle and baked in an receipient) and pullapitko (a long pulla that is made from three or four long parts that are crossed. May have raisins or sugar on top).

Anyone interested can easily find pictures on the net with the original names.

slavery. But, my maternal lineage is Haplogroup H which populates 40% to 50% of Europe. I have very dark-skin with slanted eyes and high cheekbones contibuting some of my physical traits to Native American ancestry. After having five beautiful grandchildren the slanted eyes and high cheek bones remains dominant in my grandchildren, so I decided to have a DNA test done. And these are my results: Finnish, Russian and Yoruba. Most of my mtDNA matches are in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Tennessee and California areas in the United States. Ouside the United States most of my matches are England and Germany compared with the participaants in the DNA database at Family TreeDNA.

There is still a highly Finnish population in some parts of Minnesota's Iron Range area. Embarrass has it's own Finn Fest every summer, along with tours of a traditional Finnish homestead, and an artisan/historygroup called Sisu Heritage. I can recommend any of those if someone were interested.

Also, just as a correction, the Minnesota Twins pitcher was Kevin Tapani, not Rick as stated in the article.

All four of my grandparents came from Finland, then, via Ellis Island, they traveled directly to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, to work in the iron mines, where my dad also worked and where I grew up in the 50's, with a lot of Finns and traditions still maintained, but very much Americanized, and patriotic, as well.

Dianne

I'm a Fenno-Swede, or what you refer to as a "Finland Swede", fluent in both official languages of Finland. To point out my pink elephant, at least where I come from, a "Swede Finn" refers to a Finn living in Sweden. Fenno-Swedes are the Swedish-speaking minority group, who form about 6% of the population of Finland.

I have to point out, that a lot of the Finnish words are correct, but they are misspelled, or mis-translated; Reiska is a man's name, "rieska" is the flatbread you intended to name.

The proverb "jos ei viina, terva ja sauna auta, on tauti kuolemaksi" refers to clear liquor, like vodka (or moonshine), not whiskey, and the tar is not a salve, it's specifically pine tar, that is extracted from pine trees, and used to waterproof slate roofs in old buildings, and wooden boats, but also served on top of sugar cubes at traditional tar pits as a "health tonic".

The greetings and popular expressions section provides good pronunciation guides for most words, however, it omits long vowels where they are due, since Finns spell words phonetically; if a word has a long vowel sound, it is spelled that way, so the correct spellings for those "good something"-greetings would be: Hyvää päivää; Hyvää iltaa, Hauskaa Joulua (the word for Christmas derives from the same old Norse that spawned the English name "Yule"); Hyvää huomenta... and "olkaa hyvä", is the colloquial equivalent to "you're welcome", but can be used as "please" for requests like "sit down, please". Finnish lacks an exact word equivalent to "please", and sometimes Finns conversing in English come off as rude, if they aren't familiar with English phrases.

"The Working Woman" was a strange translation for the magazine name "Toveritar", as the word "toveri" is almost solely used as the communist "comrade", and the suffix "-tar" is used like the "-ess" in words like seamstress, baroness, and so on, to denote a female counterpart to, or spouse of a male role or occupation.

Content-wise, this article is comprehensive, and well-written, I feel more aware of what Finnish American culture has offered, and has to offer, I just have trouble letting go some details when it comes to the misspelled Finnish expressions (that evokes my father-in-law's first attempt at saying "nice to meet you/hauska tavata" in Finnish, where I thought he was speaking gibberish) my sense of propriety twitches a little. The last issue I see, is sauna and spring cleaning described as "rituals", when they would, in my opinion, be better described as "traditions", since very few Finns consider there to be any deeper, spiritual meaning with the activity, it's more one of these "my ma and pa used to do it this way"-traditions.

And as a member of the Finnish Defense Forces Reserve, I felt a little saddened by no mention of Finnish American war heroes like U.S. Army Major Larry Thorne (Lauri Törni, 1919 – 1965), or any of the other Finnish military officers known as "Marttinen's Men", of whom several were among some of the first men recruited into the new U.S. Army Special Forces.

Great articles. Very informative. Finns definetely a strong people.

Nisu is an old Finnish name for wheat. Not especially for the sweed bread or anything else. Wheat was used in Finland only for the sweet bread and therefore the confusion. Real bread was all done from rye, so this sweet bread was called nisuleipä or simply nisu.

Completely correct arguments from you. Only I would like to add about terva = tar. Tar used to be a big business in Finland when the British imported a lot of it from Finland for their large navy. It was used for the ship hulls and even more for the ropes.

She has quite a story. I was at a finnish festival in Michigan UP and ran into a man making a documentary that previously worked on a project where he learned the Arlo Guthrie song about Maggies Farm was about Maggie Walz. She started a work farm under Roosevelt on Drmmand Island. It was just fun to see her mentioned in your article.

Desiree

{My father came from Finland, although we speak Swedish}

Could your great grandmother be Alminia " Minnie" Sofia Ernberg, born 1876 and died 1909? She is listed as being the wife of Charles Goldschmidt ( born Feb 15,1877 -died Jan 25,1965)? Her father was Anders Johan Andersson /Enberg/Ernberg who emigrated to the USA in 1869 ( May 13th).They are actually from Sweden BUT as we know many Finns and Swedes married back then and even now:)There is an interesting books where her family is actually mentioned. You can find it online if you google: A History of the Swedish-Americans of Minnesota( written in 1910)

If you would like the links where I found your great grandmother's information , feel free to email me at trishpaakkonen@gmail.com OR paakkonen@aya.yale.edu Hope this helps! Trish in Finland:)

Robert (comment # 27), I will contact a few people and see if I can find someone to write your note. I will post a comment here when I have an answer. Take good care, Denise

My grandparents both sides immigrated to this country from Finland, settling in Embarrass, MN. My father's mother first immigrated to Fitchburg MA and then moved to Embarrass where other members of her family, the Palomakis had settled. She was adament about learning to speak English, told visitors at their place they had to try to visit speaking English. She taught me how to read English using those old storybooks. Until then, I spoke Finnish and rudimentary English. My maternal grandfather was a labor activist and an IWW man. He was blacklisted from the underground mines in Ely, MN and was a sustenance farmer in Waasa Township Embarrass.

My father was a manager for the Co-Operative stores for 42 years. At least half of his employees were Finnish speaking and others spoke Italian since in Mountain Iron, MN, the population was largely Finnish with Italians the second largest immigrant group. Signs in the store and in the front windows were printed in both Finnish and English. Mountain Iron businessmen were Wainio, Terrio, Maki, Kakela, Perala, Rahko, Kauppila and Anderson.

Where on earth the rest 18 million people live?

innish. I was born in Coburntown, Mi, just north of Hancock, Mi, to Aili Kilpela and Matt Einari Alatalo. We lived with my paternal grandparents, Anna and Augusti Alatalo. My husband is Finnish on his mother's side (Ojala). I have been to Finland 5 times to visit family, and the last time was with my granddaughter, who loves her Finnish heritage.

A great informative article. Thank you!

Also, greetings from Galveston, TX from Randy and I both. Perhaps you remember us from our few years around Minneapolis: Suomi koulu, FACC, and otherFinnish related activities in the area. Our daughter Majka now is with the University of Texas Medical Branch here in Galveston and Randy and I continue to help look after our now seven year old granddaughter, Anneli, and to help keep the Finnish connection.

I remember being quite amazed at the very different groups of Finns I came across in Minnesota, your article gives clarity and information, very interesting. :)

This certainly is awesome article about Finnish Americans. I live in Finland and have always been interested in the finnish american history. Some of my relatives live in Canada and my wife has relatives in Mountain Iron - area. Her great grandfather was a working as a miner there. They moved back to Finland in the 20's.

Thanks for the article.

Mika