Apaches

by D. L. Birchfield

Overview

The name "Apache" is a Spanish corruption of "Apachii," a Zuñi word meaning "enemy." Federally recognized contemporary Apache tribal governments are located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. Apache reservations are also located in Arizona and New Mexico. In Oklahoma, the Apache land was allotted in severalty under the General Allotment Act of 1887 (also known as the Dawes Act); Oklahoma Apaches became citizens of the new state of Oklahoma and of the United States in 1907. Apaches in Arizona and New Mexico were not granted U.S. citizenship until 1924. Since attempting to terminate its governmental relationship with Indian tribes in the 1950s, the United States has since adopted a policy of assisting the tribes in achieving some measure of self-determination, and the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld some attributes of sovereignty for Indian nations. In recent years Apache tribal enterprises such as ski areas, resorts, casinos, and lumber mills have helped alleviate chronically high rates of unemployment on the reservations, and bilingual and bicultural educational programs have resulted from direct Apache involvement in the educational process. As of 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that 53,330 people identified themselves as Apache, up from 35,861 in 1980.

HISTORY

Apaches have endured severe economic and political disruptions, first by the Spanish, then by the Comanches, and later by the United States government. Apaches became known to the Spanish during authorized and illegal Spanish exploratory expeditions into the Southwest during the sixteenth century, beginning with the Coronado expedition of 1540, but including a number of others, at intervals, throughout the century. It was not until 1598, however, that Apaches had to adjust to the presence of Europeans within their homeland, when the expedition of Juan de Oñate entered the Pueblo country of the upper Rio Grande River Valley in the present state of New Mexico. Oñate intended to establish a permanent Spanish colony. The expedition successfully colonized the area, and by 1610 the town of Santa Fe had been founded. Until the arrival of the Spanish, the Apaches and the Pueblos had enjoyed a mercantile relationship: Pueblos traded their agricultural products and pottery to the Apaches in exchange for buffalo robes and dried meat. The annual visits of whole Apache tribes for trade fairs with the Pueblos, primarily at the pueblos of Taos and Picuris, were described with awe by the early Spaniards in the region. The Spanish, however, began annually to confiscate the Pueblo trade surpluses, thereby disrupting the trade. Nonetheless some Apaches, notably the Jicarillas, became friends and allies of the Spanish. A small group broke away from the Eastern Apaches in the 1600s and migrated into Texas and northern Mexico. This band became known as the Lipan Apaches and was subsequently enslaved by Spanish explorers and settlers from Mexico in the 1700s. They were forced to work on ranches and in mines. The surviving Lipan Apaches were relocated to the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico in 1903.

The historic southward migration of the Comanche Nation, beginning around 1700, was devastating for the Eastern Apaches. By about 1725 the Comanches had established authority throughout the whole of the Southern Plains region, pushing the Eastern Apaches (the Jicarillas north of Santa Fe, and the Mescaleros south of Santa Fe) into the mountains of the front range of the Rockies in New Mexico. Denied access to the buffalo herds, the Apaches turned to Spanish cattle and horses. When the Spanish were able to conclude a treaty of peace with the Comanches in 1786, they employed large bodies of Comanche and Navajo auxiliary troops with Spanish regulars, in implementing an Apache policy that pacified the entire Southwestern frontier by 1790. Each individual Apache group was hunted down and cornered, then offered a subsidy sufficient for their maintenance if they would settle near a Spanish mission, refrain from raiding Spanish livestock, and live peacefully. One by one, each Apache group accepted the terms. The peace, though little studied by modern scholars, is thought to have endured until near the end of the Spanish colonial era.

The start of the Mexican War with the United States in 1846 disrupted the peace, and by the time the United States moved into the Southwest at the conclusion of the Mexican War in 1848, the Apaches posed an almost unsolvable problem. The Americans, lacking both Spanish diplomatic skills and Spanish understanding of the Apaches, sought to subjugate the Apaches militarily, an undertaking that was not achieved until the final surrender of Geronimo's band in 1886. Some Apaches became prisoners of war, shipped first to Florida, then to Alabama, and finally to Oklahoma. Others entered a period of desultory reservation life in the Southwest.

MODERN ERA

Apache populations today may be found in Oklahoma, Arizona, and New Mexico. The San Carlos Reservation in eastern Arizona occupies 1,900,000 acres and has a population of more than 6,000. The San Carlos Reservation and Fort Apache Reservation were administratively divided in 1897. In the 1920s the San Carlos Reservation established a business committee, which was dominated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The business committee evolved into a tribal council, which now runs the tribe as a corporation. The reservation lost most of its best farmland when the Coolidge Dam was completed in 1930. Mount Graham, 10,720 feet in elevation, is sacred land to the Apaches. It stands at the southern end of the reservation. The Tonto Reservation in east-central Arizona is a small community, closely related to the Tontos at Camp Verde Reservation.

The Fort Apache Reservation occupies 1,665,000 acres in eastern Arizona and has a population of more than 12,000. It is home to the Coyotero Apaches which include the Cibecue and White Mountain Apaches. Approximately half of the land is timbered; there is diverse terrain with different ecosystems depending upon the elevation, from 2,700 feet to 11,500 feet. Fort Apache was founded as a military post in 1863 and decommissioned in 1922. The Fort Apache Recreation Enterprise, begun in 1954, has created much economic activity, including Sunrise Ski Area, which generates more than $9 million in revenue annually. In 1993, the White Mountain Apaches opened the Hon Dah (Apache for "Welcome") Casino on the Fort Apache Reservation.

The Camp Verde Reservation occupies approximately 500 acres in central Arizona. The reservation, in several small fragments, is shared by about an equal number of Tonto Apaches and Yavapai living in three communities, at Camp Verde, Middle Verde, and Clarksdale. About half of the 1,200 tribal members live on the reservation. Middle Verde is the seat of government, a tribal council that is elected from the three communities. The original tract of 40 acres, acquired in 1910, is at Camp Verde. By 1916, an additional 400 acres had been added at Middle Verde. In 1969, 60 acres were acquired at Clarksdale, a donation of the Phelps-Dodge Company when it closed its Clarksdale mining operation, to be used as a permanent land base for the Yavapai-Apache community that had worked in the Clarksdale copper mines. An additional 75 acres of tribal land surrounds the Montezuma Castle National Monument. Approximately 280 acres at Middle Verde is suitable for agriculture. The tribe has the highest percentage of its students enrolled in college of any tribe in Arizona.

The Jicarilla Reservation occupies 750,000 acres in north-central New Mexico. There are two divisions among the Jicarilla, the Olleros ("Potmakers") and the Llaneros ("Plains People"). Jicarilla is a Spanish word meaning "Little Basket." In 1907, the reservation was enlarged, with the addition of a large block of land to the south of the original section. In the 1920s, most Jicarilla were stockmen. Many lived on isolated ranches, until drought began making sheep raising unprofitable. After World War II, oil and gas were discovered on the southern portion of the reservation, which by 1986 was producing annual income of $25 million (which dropped to $11 million during the recession in the early 1990s). By the end of the 1950s, 90 percent of the Jicarilla had moved to the vicinity of the agency town of Dulce.

The Mescalero Reservation occupies 460,000 acres in southeast New Mexico in the Sacramento Mountains northeast of Alamogordo. Located in the heart of a mountain recreational area, the Mescaleros have taken advantage of the scenic beauty, bringing tourist dollars into their economy with such enterprises as the Inn of the Mountain Gods, which offers several restaurants and an 18-hole golf course. Another tribal operation, a ski area named Ski Apache, brings in more revenue. The nearby Ruidoso Downs horse racing track also attracts visitors to the area. From mid-May to mid-September, lake and stream fishing is accessible at Eagle Creek Lakes, Silver Springs, and Rio Ruidoso recreation areas. The Mescaleros, like the Jicarilla, are an Eastern Apache tribe, with many cultural influences from the Southern Great Plains.

Apaches in Oklahoma, except for Kiowa-Apaches, are descendants of the 340 members of Geronimo's band of Chiricahua Apaches. The Chiricahua were held as prisoners of war, first in 1886 at Fort Marion, Florida, then for seven years at Mount Vernon Barracks, Alabama, and finally at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. By the time they arrived in Fort Sill on October 4, 1894, their numbers had been reduced by illness to 296 men, women and children. They remained prisoners of war on the Fort Sill Military Reservation until 1913. In that year, a total of 87 Chiricahua were allotted lands on the former Kiowa-Comanche Reservation, not far from Fort Sill.

The Kiowa-Apache are a part of the Kiowa Nation. The Kiowa-Apache are under the jurisdiction of the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Agency of the Anadarko Area Office of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In the 1950s, the Kiowa-Apache held two seats on the 12-member Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Business Committee. Elections for the Kiowa-Apache seats on the Business Committee were held every four years at Fort Cobb. The Kiowas and the Comanches now have separate business committees, which function as the equivalent of tribal governments, and the Kiowa-Apaches have remained allied with the Kiowas. The Kiowa-Apache are an Athapascan-speaking people. They are thought to have diverged from other Athapascans in the northern Rocky Mountains while the Southern Athapascans were in the process of migrating to the Southwest. They became allied with the Kiowas, who at that time lived near the headwaters of the Missouri River in the high Rockies, and they migrated to the Southern Plains with the Kiowas, stopping en route for a time in the vicinity of the Black Hills. Since they first became known to Europeans, they have been closely associated with the Kiowas on the Great Plains. The Lewis and Clark expedition met the Kiowa-Apaches in 1805 and recorded the first estimate of their population, giving them an approximate count of 300. The Kiowas and the Kiowa-Apaches eventually became close allies of the Comanches on the Southern Plains. By treaty in 1868 the Kiowa-Apaches joined the Kiowas and Comanches on the same reservation. A devastating measles epidemic killed hundreds of the three tribes in 1892. In 1901, the tribal estate was allotted to individual tribal members, and the remainder of their land was opened to settlement by American farmers. The Kiowa-Apache allotments are near the communities of Fort Cobb and Apache in Caddo County, Oklahoma. Official population reports for the Kiowa-Apaches put their numbers at 378 in 1871, 344 in 1875, 349 in 1889, 208 in 1896, and 194 in 1924. In 1951, historian Muriel Wright estimated their population in Oklahoma at approximately 400.

THE FIRST APACHES IN AMERICA

Apaches are, relatively speaking, new arrivals in the Southwest. Their language family, Athapascan, is dispersed over a vast area of the upper Western hemisphere, from Alaska and Canada to Mexico. Apaches have moved farther south than any other members of the Athapascan language family, which includes the Navajo, who are close relatives of the Apaches. When Spaniards first encountered the Apaches and Navajos in the sixteenth century, they could not tell them apart and referred to the Navajo as Apaches de Navajo.

Athapascans are generally believed to have been among the last peoples to have crossed the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska during the last interglacial epoch. Most members of the language family still reside in the far north. Exactly when the Apaches and Navajos began their migration southward is not known, but it is clear that they had not arrived in the Southwest before the end of the fourteenth century. The Southwest was home to a number of flourishing civilizations—the ancient puebloans, the Mogollon, the Hohokum, and others—until near the end of the fourteenth century. Those ancient peoples are now believed to have become the Papago, Pima, and Pueblo peoples of the contemporary Southwest. Scholars at one time assumed that the arrival of the Apaches and Navajos played a role in the abandonment of those ancient centers of civilization. It is now known that prolonged drought near the end of the fourteenth century was the decisive factor in disrupting what was already a delicate balance of life for those agricultural cultures in the arid Southwest. The Apaches and Navajos probably arrived to find that the ancient puebloans in the present-day Four Corners area had reestablished themselves near dependable sources of water in the Pueblo villages of the upper Rio Grande Valley in what is now New Mexico, and that the Mogollon in southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona and the Hohokam in southern Arizona had likewise migrated from their ancient ruins. When Spaniards first entered the region, with the expedition of Francisco de Coronado in 1540, the Apaches and Navajos had already established themselves in their homeland.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

The Grand Apacheria, as it was known, the homeland of the Apaches, was a vast region stretching from what is now central Arizona in the west to present-day central and south Texas in the east, and from northern Mexico in the south to the high plains of what became eastern Colorado in the north. This region was divided between Eastern and Western Apaches. Eastern Apaches were Plains Apaches. In the days before the horse, and before the historic southward migration of the Comanche Nation, in the early 1700s, the Plains Apaches were the lords of the Southern Plains. Western Apaches lived primarily on the western side of the Continental Divide in the mountains of present-day Arizona and western New Mexico. When the Comanches adopted the use of the horse and migrated southward out of what is now Wyoming, they displaced the Eastern Apaches from the Southern Great Plains, who then took up residence in the mountainous country of what eventually became eastern New Mexico.

Acculturation and Assimilation

While adhering strongly to their culture in the face of overwhelming attempts to suppress it, Apaches have been adaptable at the same time. As an example, approximately 70 percent of the Jicarillas still practice the Apache religion. When the first Jicarilla tribal council was elected, following the reforms of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, ten of its 18 members were medicine men and five others were traditional leaders from chiefs' families. In 1978, a survey found that at least one-half of the residents of the reservation still spoke Jicarilla, and one-third of the households used it regularly. Jicarilla children in the 1990s, however, prefer English, and few of the younger children learn Jicarilla today. The director of the Jicarilla Education Department laments the direction such changes are taking, but no plans are underway to require the children to learn Jicarilla. At the same time, Jicarillas are demonstrating a new pride in traditional crafts. Basketry and pottery making, which had nearly died out during the 1950s, are now valued skills once again, taught and learned with renewed vigor. Many Apaches say they are trying to have the best of both worlds, attempting to survive in the dominant culture while still remaining Apache.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

The most enduring Apache custom is the puberty ceremony for girls, held each summer. Clan relatives still play important roles in these ceremonies, when girls become Changing Woman for the four days of their nai'es. These are spectacular public events, proudly and vigorously advertised by the tribe.

EDUCATION

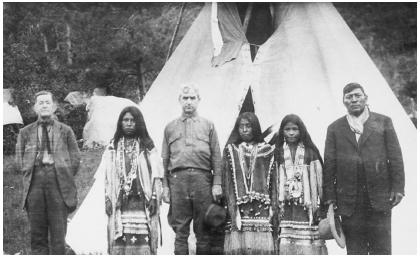

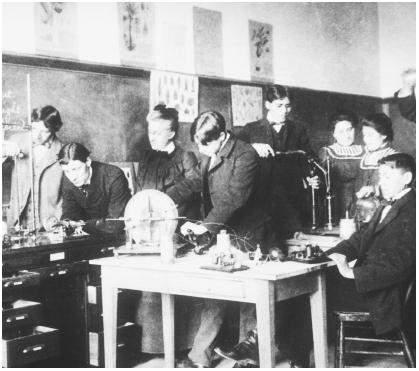

Many Apache children were sent to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania not long after the school was founded in 1879 by Richard Henry Pratt; a large group of them arrived in 1887. Government and mission schools were established among the Apaches in the 1890s. These schools pursued vigorous assimilationist policies, including instruction only in English. By 1952, eighty percent of the Apaches in Arizona spoke English. Today, Apaches participate in decisions involving the education of their young, and this has resulted in exemplary bilingual and bicultural programs at the public schools at the San Carlos and Fort Apache reservations, especially in the elementary grades. In 1959, the Jicarilla in New Mexico incorporated their school district with the surrounding Hispanic towns. Within 30 years, its school board included four Jicarilla members, including the editor of the tribal newspaper. In 1988, the Jicarilla school district was chosen New Mexico School District of the Year.

Some Apache communities, like the Cibecue community at White Mountain Reservation, are more conservative and traditional than others, but all value their traditional culture, which has proven to be enduring. Increasingly, especially in communities such as the White Mountain Reservation, education is being used as a tool to develop human resources so that educated tribal members can find ways for the tribe to engage in economic activity that will allow more of its people to remain on the reservation, thus preserving its community and culture.

CUISINE

Baked mescal, a large desert agave plant, is a uniquely traditional Apache food and is still occasionally harvested and prepared. The proper season for harvesting is May or June, when massive red flowers begin to appear in the mescal patches; it requires specialized knowledge just to find them. The plant is dug out of the ground and stripped, leaving a white bulb two to three feet in circumference. A large cooking pit is dug, about 15 feet long, four feet wide, and four feet deep, large enough to cook about 2,000 pounds of mescal. The bottom of the pit is lined with stones, on top of which fires are built. The mescal is layered on top of the stones, covered with a layer of straw, and then with a layer of dirt. When cooked, the mescal is a fibrous, sticky, syrupy substance with a flavor similar to molasses. Portions are also dried in thin layers, which can last indefinitely without spoiling, and which provide the Apaches with lightweight rations for extended journeys.

CRAFTS

Reconstructed traditional houses of the Apache, Maricopa, Papago, and Pima are on display at the Gila River Arts and Crafts Museum in Sacaton, Arizona, south of Phoenix. The gift shop at the

DANCES AND SONGS

Charlotte Heth, of the Department of Ethnomusicology, University of California, Los Angeles, has noted in a chapter in Native America: Portrait of the Peoples that "Apache and Navajo song style are similar: tense, nasal voices; rhythmic pulsation; clear articulation of words in alternating sections with vocables. Both Apache Crown Dancers and Navajo Yeibichei (Night Chant) dancers wear masks and sing partially in falsetto or in voices imitating the supernaturals."

The White Mountain Apache Sunrise Dance signifies a girl's entrance into womanhood. When a girl performs the elaborate dance she will be bestowed with special blessings. The ceremony involves the parents choosing godparents for the girl. Also, a medicine man is selected to prepare the sacred items used in the four-day event, including an eagle feather for the girl's hair, deer skin clothing, and paint made from corn and clay. The dance itself lasts three to six hours and is performed twice to 32 songs and prayers. The Crown Dance or Mountain Spirit Dance is a masked dance in which the participants impersonate deities of the mountains—specifically the Gans, or mountain spirits. The Apache Fire Dance is also a masked dance. Instruments for making music include the water drum, the hand-held rattle, and the human voice. Another traditional instrument still used in ritual and ceremonial events is the bullroarer, a thin piece of wood suspended from a string and swung in a circle. Not all dances are open to the public. Visitors should call the tribal office to find out when dances are scheduled at which they will be welcome. The Yavapai-Apache,

HOLIDAYS

Apaches celebrate a number of holidays each year with events that are open to the public. The San Carlos Apache Tribal Fair is celebrated annually over Veterans Day weekend at San Carlos, Arizona. The Tonto Apache and Yavapai-Apache perform public dances each year at the Coconino Center for the Arts, Flagstaff, Arizona, on the Fourth of July. The White Mountain Apache host The Apache Tribal Fair, which usually occurs on Labor Day weekend, at Whiteriver, Arizona. The Jicarilla Apache host the Little Beaver Rodeo and Powwow, usually in late July, and the Gojiiya Feast Day on September 14-15 each year, at Dulce, New Mexico. The Mescalero Apache Gahan Ceremonial occurs each year on July 1-4 at Mescalero, New Mexico. Apaches in Oklahoma participate in the huge, week-long American Indian Exposition in Anadarko, Oklahoma, each August.

HEALTH ISSUES

Apaches have suffered devastating health problems from the last decades of the nineteenth century and throughout most of the twentieth century. Many of these problems are associated with malnutrition, poverty, and despair. They have suffered incredibly high rates of contagious diseases such as tuberculosis. Once tuberculosis was introduced among the Jicarilla, it spread at an alarming rate. The establishment of schools, beginning in 1903, only gave the tuberculosis bacteria a means of spreading rapidly throughout the entire tribe. By 1914, 90 percent of the Jicarillas suffered from tuberculosis. Between 1900 and 1920, one-quarter of the people died. One of the reservation schools had to be converted into a tuberculosis sanitarium in an attempt to address the crisis. The sanitarium was not closed until 1940.

Among nearly all Native peoples of North America, alcohol has been an insidious, destructive force, and the Apache are no exception. A recent study found that on both the Fort Apache Reservation and the San Carlos Reservation, alcohol was a factor in more than 85 percent of the major crimes. Alcohol, though long known to the Apache, has not always been a destructive force. Sharing the traditional telapi (fermented corn sprouts), in the words of one elder, "made people feel good about each other and what they were doing together." Alcohol as a destructive force in Apache culture is a phenomenon that dates from colonization, and it has been a byproduct of demoralization and despair. Tribal leaders have attempted to address the underlying health problems by trying to create tribal enterprise, by fostering and encouraging bilingual and bicultural educational opportunities, and by trying to make it possible for Apaches to gain more control over their lives.

Language

The Athapascan language family has four branches: Northern Athapascan, Southwestern Athapascan, Pacific Coast Athapascan, and Eyak, a southeast Alaska isolate. The Athapascan language family is one of three families within the Na-Dene language phylum; the other two, the Tlingit family and the Haida family, are language isolates in the far north, Tlingit in southeast Alaska, and Haida in British Columbia. Na-Dene is one of the most widely distributed language phyla in North America. The Southwestern Athapascan language, sometimes called Apachean, has seven dialects: Navajo, Western Apache, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Lipan, and Kiowa-Apache.

Family and Community Dynamics

For the Apaches, the family is the primary unit of political and cultural life. Apaches have never been a unified nation politically, and individual Apache tribes, until very recently, have never had a centralized government, traditional or otherwise. Extended family groups acted entirely independently of one another. At intervals during the year a number of these family groups, related by dialect, custom, inter-marriage, and geographical proximity, might come together, as conditions and circumstances might warrant. In the aggregate, these groups might be identifiable as a tribal division, but they almost never acted together as a tribal division or as a nation—not even when faced with the overwhelming threat of the Comanche migration into their Southern Plains territory. The existence of these many different, independent, extended family groups of Apaches made it impossible for the Spanish, the Mexicans, or the Americans to treat with the Apache Nation as a whole. Each individual group had to be treated with separately, an undertaking that proved difficult for each colonizer who attempted to establish authority within the Apache homeland.

Apache culture is matrilineal. Once married, the man goes with the wife's extended family, where she is surrounded by her relatives. Spouse abuse is practically unknown in such a system. Should the marriage not endure, child custody quarrels are also unknown: the children remain with the wife's extended family. Marital harmony is encouraged by a custom forbidding the wife's mother to speak to, or even be in the presence of, her son-in-law. No such stricture applies to the wife's grandmother, who frequently is a powerful presence in family life. Apache women are chaste, and children are deeply loved.

Employment and Economic Traditions

Apaches can be found pursuing careers in all the professions, though most of them must leave their communities to do so. Some are college faculty; others, such as Allan Houser, grand-nephew of Geronimo, have achieved international reputations in the arts. Farming and ranching continue to provide employment for many Apaches, and Apaches have distinguished themselves as some of the finest professional rodeo performers.

By 1925, the Bureau of Indian Affairs had leased nearly all of the San Carlos Reservation to non-Indian cattlemen, who demonstrated no concern about overgrazing. Most of the best San Carlos farmland was flooded when Coolidge Dam was completed in 1930. Recreational concessions around the lake benefit mostly non-Natives. By the end of the 1930s, the tribe regained control of its rangeland and most San Carlos Apaches became stockmen. Today, the San Carlos Apache cattle operation generates more than $1 million in sales annually. Cattle, timber, and mining leases provide additional revenue. There is some individual mining activity for the semiprecious peridot gemstones. A chronic high level of unemployment is the norm on most reservations in the United States. More than 50 percent of the tribe is unemployed. The unemployment rate on the reservation itself is about 20 percent. U.S. Census Bureau figures show the median family income for Apaches was $19,690, which is $16,000 less than for the general population. Also, 37.5 percent of Apaches had incomes at or below the poverty level as of 1989.

A number of tribal economic enterprises offer some employment opportunities. The Fort Apache Timber Company in Whiteriver, Arizona, owned and operated by the White Mountain Apache, employs about 400 Apache workers. It has a gross annual income of approximately $30 million, producing 100 million board feet of lumber annually (approximately 720,000 acres of the reservation is timberland). The tribe also owns and operates the Sunrise Park Ski Area and summer resort, three miles south of McNary, Arizona. It is open year-round, and contributes both jobs and tourist dollars to the local economy. The ski area has seven lifts and generates $9 million in revenue per year. Another tribally owned enterprise is the White Mountain Apache Motel and Restaurant. The White Mountain Apache Tribal Fair is another important event economically.

The Jicarilla Apache also operate a ski enterprise, offering equipment rentals and trails for a cross-country ski program during the winter months. The gift shop at the Jicarilla museum provides an outlet for the sale of locally crafted Jicarilla traditional items, including basketry, beadwork, feather work, and finely tanned buckskin leather.

Many members of the Mescalero Apache find employment at their ski resort, Ski Apache. Others work at the tribal museum and visitor center in Mescalero, Arizona. A 440-room Mescalero resort, the Inn of the Mountain Gods, has a gift shop, several restaurants, and an 18-hole golf course, and offers casino gambling, horseback riding, skeet and trap shooting, and tennis. The tribe also has a 7,000-head cattle ranch, a sawmill, and a metal fabrication plant. In 1995, the Mescaleros signed a controversial $2 billion deal with 21 nuclear power plant operators to store nuclear waste on a remote corner of the reservation. The facility is scheduled to open in 2002, barring any legal challenges.

For the Yavapai-Apache, whose small reservation has fewer than 300 acres of land suitable for agriculture, the tourist complex at the Montezuma Castle National Monument—where the tribe owns the 75 acres of land surrounding the monument—is an important source of employment and revenue.

Tourism, especially for events such as tribal fairs and for hunting and fishing, provides jobs and brings money into the local economies at a number of reservations. Deer and elk hunting are especially popular on the Jicarilla reservation. The Jicarilla also maintain five campgrounds where camping is available for a fee. Other campgrounds are maintained by the Mescalero Apache (3), the San Carlos Apache (4), and the White Mountain Apache (18).

Politics and Government

The Apache tribes are federally recognized tribes. They have established tribal governments under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (25 U.S.C. 461-279), also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act, and they successfully withstood attempts by the U.S. government to implement its policy during the 1950s of terminating Indian tribes. The Wheeler-Howard Act, however, while allowing some measure of self-determination in their affairs, has caused problems for virtually every Indian nation in the United States, and the Apaches are no exception. The act subverts traditional Native forms of government and imposes upon Native people an alien system, which is something of a mix of American corporate and governmental structures. Invariably, the most traditional people in each tribe have had little to say about their own affairs, as the most heavily acculturated and educated mixed-blood factions have dominated tribal affairs in these foreign imposed systems. Frequently these tribal governments have been little more than convenient shams to facilitate access to tribal mineral and timber resources in arrangements that benefit everyone but the Native people, whose resources are exploited. The situations and experiences differ markedly from tribe to tribe in this regard, but it is a problem that is, in some measure, shared by all.

RELATIONS WITH THE UNITED STATES

Apaches were granted U.S. citizenship under the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. They did not legally acquire the right to practice their Native religion until the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (42 U.S.C. 1996). Other important rights, and some attributes of sovereignty, have been restored to them by such legislation as the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1966 (25 U.S.C. 1301), the Indian Self-Determination and Educational Assistance Act of 1975 (25 U.S.C. 451a), and the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (25 U.S.C. 1901). Under the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946, the Jicarillas have been awarded nearly $10 million in compensation for land unjustly taken from them, but the United States refuses to negotiate the return of any of this land. In Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Jicarillas in an important case concerning issues of tribal sovereignty, holding that the Jicarillas have the right to impose tribal taxes upon minerals extracted from their lands.

Individual and Group Contributions

LITERATURE, ACADEMIA, AND THE ARTS

Apaches are making important contributions to Native American literature and the arts. Lorenzo Baca, of Mescalero Apache and Isleta Pueblo heritage, is not only a writer, but also a performing and visual artist who does fine art, sculpture, video, storytelling and acting. His poetry has been anthologized in The Shadows of Light: Poetry and Photography of the Motherlode and Sierras (Jelm Mountain Publications), in Joint Effort II: Escape (Sierra Conservation Center), and in Neon Powwow: New Native American Voices of the Southwest (Northland Publishing). His audio recording, Songs, Poems and Lies, was produced by Mr. Coyote Man Productions. An innovative writer, his circle stories entitled "Ten Rounds" in Neon Powwow illustrate his imagination and capacity to create new forms of poetic expression. Jicarilla Apache creative writers Stacey Velarde and Carlson Vicenti present portraits of Native people in the modern world in their stories in the Neon Powwow anthology. Velarde, who has been around horses all her life and has competed in professional rodeos since the age of 13, applies this background and knowledge in her story "Carnival Lights," while Vicenti, in "Hitching" and "Oh Saint Michael," shows how Native people incorporate traditional ways into modern life.

White Mountain Apache poet Roman C. Adrian has published poetry in Sun Tracks, The New Times, Do Not Go Gentle, and The Remembered Earth. The late Chiricahua Apache poet Blossom Haozous, of Fort Sill, Oklahoma, was a leader in the bilingual presentation of Apache traditional stories, both orally and in publication. One of the stories, "Quarrel Between Thunder and Wind" was published bilingually in the Chronicles of Oklahoma, the quarterly scholarly journal of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Jose L. Garza, Coahuilateca and Apache, is not only a leading Native American poet but a leading Native American educator as well. His poetry has appeared in such publications as Akwe:kon Journal, of the American Indian Program at Cornell University, The Native Sun, New Rain Anthology, The Wayne Review, Triage, and The Wooster Review. Garza is a professor at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania and is a regional coordinator of Wordcraft Circle of Native American Mentor and Apprentice Writers. In Wordcraft Circle, he organizes and helps conduct intensive writing workshops in which young Native writers from all tribes have an opportunity to hone their creative skills and learn how they can publish their work.

Other Apache writers include Lou Cuevas, author of Apache Legends: Songs of the Wild Dancer and In the Valley of the Ancients: A Book of Native American Legends (both Naturegraph); Jicarilla Apache scholar Veronica E. Velarde Tiller, the author of The Jicarilla Apache Tribe (University of Nebraska Press); and Michael Lacapa, of Apache, Hopi, and Pueblo heritage, the author of The Flute Player, Antelope Woman: An Apache Folktale, and The Mouse Couple (all Northland). Throughout the Apache tribes, the traditional literature and knowledge of the people is handed down from generation to generation by storytellers who transmit their knowledge orally.

VISUAL ARTS

Chiricahua Apache sculptor Allan Houser has been acclaimed throughout the world for his six decades of work in wood, marble, stone, and bronze. Houser was born June 30, 1914, near Apache, Oklahoma. He died on August 22, 1994, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His Apache surname was Haozous, which means "Pulling Roots."

In the 1960s, Houser was a charter faculty member at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, where he began to cast statues in bronze. He taught until 1975. After retirement from teaching, he devoted himself full-time to his work, creating sculptures in bronze, wood, and stone. In April 1994, he presented an 11-foot bronze sculpture to first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton in Washington, D.C., as a gift from the American Indians to all people.

Houser was known primarily for his large sculptures. Many of these could be seen in a sculpture garden, arranged among pinon and juniper trees, near his studio. His work is included in the British Royal Collection, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, the Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado, the Museum of Northern Arizona at Flagstaff, Arizona, the Linden Museum in Stuttgart, Germany, the Fine Arts Museum of the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Apache Tribal Cultural Center in Apache, Oklahoma, the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the University Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Houser's work has won many awards, including the Prix de West Award in 1993 for a bronze sculpture titled "Smoke Signals" at the annual National Academy of Western Art show at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. "Smoke Signals" is now a part of the permanent collection of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

One of his best known works, a bronze statue of an Indian woman, titled "As Long as the Waters Flow," stands in front of the state capitol of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City. At the University of Oklahoma, in Norman, two large Houser sculptures were on loan to the university and on display on the grounds of the campus at the time of his death. At the Fred Jones Jr. Museum on campus several Houser pieces from private Oklahoma collections were on view. Upon his death, the University of Oklahoma Student Association announced the creation of the Allan Houser Memorial Sculpture Fund. The fund will be used to purchase a major Houser sculpture for permanent display on the University of Oklahoma campus.

Jordan Torres (1964– ) is a Mescalero Apache sculptor from the tribe's reservation near Ruidoso, New Mexico. His work illustrates the Apache way of life. It includes "Forever," an alabaster sculpture of an Apache warrior carrying a shield and blanket; and a white buffalo entitled "On the Edge."

Media

Apache Drumbeat.

Address: Bylas, Arizona 85530.

Apache Junction Independent.

Community newspaper.

Contact: Jim Files, Editor.

Address: Independent Newspapers, Inc., 201 West Apache Trail, Suite 107, Apache Junction, Arizona 85220.

Telephone: (480) 982-7799.

Apache News.

Community newspaper founded in 1901.

Contact: Stanley Wright, Editor.

Address: Box 778, Apache, Oklahoma 73006.

Telephone: (405) 588-3862.

Apache Scout.

Address: Mescalero, New Mexico 88340.

Bear Track.

Address: 1202 West Thomas Road, Phoenix, Arizona 85013.

Center for Indian Education News.

Address: 302 Farmer Education Building, Room 302, Tempe, Arizona 85287.

Drumbeat.

Address: Institute of American Indian Arts, Cerrillos Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501.

Fort Apache Scout.

Bi-weekly community newspaper.

Address: Box 898, Whiteriver, Arizona 85941.

Telephone: (520) 338-4813.

Four Directions.

Address: 1812 Las Lomas, N.E., Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131.

Gila River Indian News.

Address: Box 97, Sacaton, Arizona 85247.

Jicarilla Chieftain.

Contact: Mary F. Polanco, Editor.

Address: P.O. Box 507, Dulce, New Mexico 87528.

Telephone: (505) 759-3242.

Fax: (505) 759-3005.

San Carlos Moccasin.

Address: P.O. Box 775, San Carlos, Arizona 85550.

Smoke Dreams.

High school newspaper for Apache students.

Address: Riverside Indian School, Anadarko, Oklahoma 73005.

Thunderbird.

High school newspaper for Apache students.

Address: Albuquerque Indian School, 1000 Indian School Road, N.W., Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103.

UTS'ITTISCTAAN'I.

Address: Northern Arizona University, Campus Box 5630, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011.

RADIO

KCIE-FM (90.5).

Jicarilla Apache radio station.

Contact: Warren Cassador, Station Manager.

Address: P.O. Box 603, Dulce, New Mexico 87528.

Telephone: (505) 759-3681.

Fax: (505) 759-3005.

KENN. Address: 212 West Apache, Farmington, New Mexico 87401.

Telephone: (505) 325-3541.

KGAK-AM. Address: 401 East Coal Road, Gallup, New Mexico 87301-6099.

Telephone: (505) 863-4444.

KGHR-FM (91.5).

Address: P.O. Box 160, Tuba City, Arizona 86519.

Telephone: (520) 283-6271, Extension 177.

Fax: (520) 283-6604.

KHAC-AM (1110).

Address: Drawer F, Window Rock, Arizona 86515.

KNNB-FM (88.1).

White Mountain Apache radio station. Eclectic and ethnic format 18 hours daily.

Contact: Phoebe L. Nez, General Manager.

Address: Highway 73, Skill Center Road, P.O. Box 310, Whiteriver, Arizona 85941.

Telephone: (520) 338-5229.

Fax: (520) 338-1744.

KPLZ.

Address: 816 Sixth Street, Parker, Arizona 85344-4599.

Address: 115 West Broadway Street, Anadarko, Oklahoma 73005.

Telephone: (405) 247-6682.

KTDB-FM (89.7). Address: P.O. Box 89, Pine Hill, New Mexico 87321.

KTNN-AM. Address: P.O. Box 2569, Window Rock, Arizona 86515.

Telephone: (520) 871-2582.

TELEVISION

KSWO-TV. Address: P.O. Box 708, Lawton, Oklahoma 73502.

Organizations and Associations

Apache Tribe of Oklahoma.

Address: P.O. Box 1220, Anadarko, Oklahoma 73005.

Telephone: (405) 247-9493.

Fax: (405) 247-9232.

Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma.

Address: Rural Route 2, Box 121, Apache, Oklahoma 73006.

Telephone: (405) 588-2298.

Fax: (405) 588-3313.

Jicarilla Apache Tribe.

Address: P.O. Box 147, Dulce, New Mexico 87528.

Telephone: (505) 759-3242.

Fax: (505) 759-3005.

Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

Address: P.O. Box 369, Carnegie, Oklahoma 73015.

Telephone: (405) 654-2300.

Fax: (405) 654-2188.

Mescalero Apache Tribe.

Address: P.O. Box 176, Mescalero, New Mexico 88340.

Telephone: (505) 671-4495.

Fax: (505) 671-4495.

New Mexico Commission on Indian Affairs.

Address: 330 East Palace Avenue, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501.

New Mexico Indian Advisory Commission.

Address: Box 1667, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87107.

San Carlos Apache Tribe.

Address: P.O. Box O, San Carlos, Arizona, 85550.

Telephone: (520) 475-2361.

Fax: (520) 475-2567.

Tonto Apache Tribal Council.

Address: Tonto Reservation No. 30, Payson, Arizona 85541.

Telephone: (520) 474-5000.

Fax: (520) 474-9125.

White Mountain Apache Tribe.

Contact: Dallas Massey Sr., Tribal Council Chairman.

Address: P.O. Box 700, Whiteriver, Arizona 85941.

Telephone: (520) 338-4346.

Fax: (520) 338-1514.

Yavapai-Apache Tribe.

Address: P.O. Box 1188, Camp Verde, Arizona.

Telephone: (520) 567-3649.

Fax: (520) 567-9455.

Museums and Research Centers

Apache museums and research centers include: Albuquerque Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico; American Research Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico; Art Center in Roswell, New Mexico; Bacone College Museum in Muskogee, Oklahoma; Black Water Draw Museum in Portales, New Mexico; Coronado Monument in Bernalillo, New Mexico; Ethnology Museum in Santa Fe; Fine Arts Museum in Santa Fe; Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma; Great Plains Museum in Lawton, Oklahoma; Hall of the Modern Indian in Santa Fe; Heard Museum of Anthropology in Phoenix, Arizona; Indian Hall of Fame in Anadarko, Oklahoma; Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe; Maxwell Museum in Albuquerque; Milicent Rogers Museum in Taos, New Mexico; Northern Arizona Museum in Flagstaff; Oklahoma Historical Society Museum in Oklahoma City; Philbrook Museum in Tulsa; Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko; State Museum of Arizona in Tempe; Stovall Museum at the University of Oklahoma in Norman; San Carlos Apache Cultural Center in Peridot, Arizona.

Sources for Additional Study

Buskirk, Winfred. The Western Apache. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.

Forbes, Jack D. Apache, Navajo, and Spaniard. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969, 1994.

Kenner, Charles L. A History of New Mexican-Plains Indian Relations. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969, 1994.

Perry, Richard J. Apache Reservation: Indigenous Peoples and the American State. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993.

Stockel, H. Henrietta. Women of the Apache Nation: Voices of Truth. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1991.

Trimble, Stephen. The People: Indians of the American Southwest. Santa Fe: New Mexico: Sar Press, 1993.

Wright, Muriel H. A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma, foreword by Arrell Morgan Gibson. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951, 1986.

Thank you from all of us at the Mescalero Apache School.

in the 1911 they moved to the Mescalero Apache Rez New Mexico, and the San Carlos Apache Rez Arizona there are Chiricahua's living in the San Carlos area and Im one of the Chiricahua's my ancestors came from Sonora area.

THANK-YOU ! Leia

Can anyone tell me about Carl A. Vicenti, Jicarrillo Apache, who did incredible paintings back in the 1960's? I have found photos of four of his works owned by an Arizona museum but there is no biographical information online.

Thank you and best regards, C.