Creoles

by Helen Bush Caver and Mary T. Williams

Overview

Unlike many other ethnic groups in the United States, Creoles did not migrate from a native country. The term Creole was first used in the sixteenth century to identify descendants of French, Spanish, or Portuguese settlers living in the West Indies and Latin America. There is general agreement that the term "Creole" derives from the Portuguese word crioulo, which means a slave born in the master's household. A single definition sufficed in the early days of European colonial expansion, but as Creole populations established divergent social, political, and economic identities, the term acquired different meanings. In the West Indies, Creole refers to a descendant of any European settler, but some people of African descent also consider themselves to be Creole. In Louisiana, it identifies French-speaking populations of French or Spanish descent. Their ancestors were upper class whites, many of whom were plantation owners or officials during the French and Spanish colonial periods. During the eighteenth and nineteenth century, they formed a separate caste that used French. They were Catholics, and retained the traditional cultural traits of related social groups in France, but they were the first French group to be submerged by Anglo-Americans. In the late twentieth century they largely ceased to exist as a distinct group. Creoles of color, the descendants of free mulattos and free blacks, are another group considered Creole in Louisiana.

HISTORY

In the seventeenth century, French explorers and settlers moved into the United States with their customs, language, and government. Their dominant presence continued until 1768 when France ceded Louisiana to Spain. Despite Spanish control, French language and customs continued to prevail.

Many Creoles, however, are descendants of French colonials who fled Saint-Domingue (Haiti) for North America's Gulf Coast when a slave insurrection (1791) challenged French authority. According to Thomas Fiehrer's essay "From La Tortue to La Louisiane: An Unfathomed Legacy," Saint-Dominque had more than 450,000 black slaves, 40,000 to 45,000 whites, and 32,000 gens-decouleur libres, who were neither white nor slaves. The slave revolt not only challenged French authority, but after defeating the expeditionary corps sent by Napoleon, the leaders of the slaves established an independent country named Haiti. Most Whites were either massacred or fled, many with their slaves, as did many mulatto freemen, many of who also owned slaves. By 1815, over 11,000 refugees had settled in New Orleans.

Toussaint L'Ouverture (1743-1803), a self-educated slave, took control of Saint-Domingue in 1801, sending more refugees to the Gulf Coast. Some exiles went directly to present-day Louisiana; others went to Cuba. Of those who went to Cuba, many came to New Orleans in the early 1800s after the Louisiana territory had been purchased by the United States (1803). This influx from Saint-Domingue and Cuba doubled New Orleans' 1791 population. Some refugees moved on to St. Martinville, Napoleonville, and Henderson, rural areas outside New Orleans. Others traveled further north along the Mississippi waterway.

In Louisiana, the term Creole came to represent children of black or racially mixed parents as well as children of French and Spanish descent with no racial mixing. Persons of French and Spanish descent in New Orleans and St. Louis began referring to themselves as Creoles after the Louisiana Purchase to set themselves apart from the Anglo-Americans who moved into the area. Today, the term Creole can be defined in a number of ways. Louisiana historian Fred B. Kniffin, in Louisiana: Its Land and People, has asserted that the term Creole "has been loosely extended to include people of mixed blood, a dialect of French, a breed of ponies, a distinctive way of cooking, a type of house, and many other things. It is therefore no precise term and should not be defined as such."

Louisiana Creoles of color were different and separate from other populations, both black and

THE FIRST CREOLES IN AMERICA

According to Virginia A. Dominguez in White By Definition, much of the written record of Creoles comes from descriptions of individuals in the baptismal, marriage, and death registers of Catholic churches of Mobile (Alabama) and New Orleans, two major French outposts on the Gulf Coast. The earliest entry is a death record in 1745 wherein a man was described as the first Creole in the colony. The term also appears in a 1748 slave trial in New Orleans.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Differences of opinion regarding the Creoles persist. The greatest controversy stems from the presence or absence of African ancestry. In an 1886 lecture at

According to Sister Dorothea Olga McCants, translator of Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes' Our People and Our History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1973), the free mixed-blood, French speakers in New Orleans came to use the word Creole to describe themselves. The phrase "Creole of color" was used by these proud part-Latin people to set themselves apart from American blacks. These Haitian descendants were cultured, educated, and economically prosperous as musicians, artists, teachers, writers, and doctors. In "Louisiana's 'Creoles of Color'," James H. Dorman has stated that the group was clearly recognized as special, productive, and worthy by the white community, citing an editorial in the New Orleans Times Picayune in 1859 that referred to them as "Creole colored people." Prior to the Civil War, a three-caste system existed: white, black, and Creoles of color. After the Civil War and Reconstruction, however, the Creoles of color—who had been part of the free black population before the war—were merged into a two-caste system, black and white.

The identification of a Creole was, and is, largely one of self-choice. Important criteria for Creole identity are French language and social customs, especially cuisine, regardless of racial makeup. Many young Creoles of color today live under pressure to identify themselves as African Americans. Several young white Creoles want to avoid being considered of mixed race. Therefore, both young black and white Creoles often choose an identity other than Creole.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

With imported furniture, wines, books, and clothes, white Creoles were once immersed in a completely French atmosphere. Part of Creole social life has traditionally centered on the French Opera House; from 1859 to 1919, it was the place for sumptuous gatherings and glittering receptions. The interior, graced by curved balconies and open boxes of architectural beauty, seated 805 people. Creoles loved the music and delighted in attendance as the operas were great social and cultural affairs.

White Creoles clung to their individualistic way of life, frowned upon intermarriage with Anglo-Americans, refused to learn English, and were resentful and contemptuous of Protestants, whom they considered irreligious and wicked. Creoles generally succeeded in remaining separate in the rural sections but they steadily lost ground in New Orleans. In 1803, there were seven Creoles to every Anglo-American in New Orleans, but these figures dwindled to two to one by 1830.

Anglo-Americans reacted by disliking the Creoles with equal enthusiasm. Gradually, New Orleans became not one city, but two. Canal Street split them apart, dividing the old Creole city from the "uptown" section where the other Americans quickly settled. To cross Canal Street in either direction was to enter another world. These differences are still noticeable today.

Older Creoles complain that many young Creoles today do not adhere to the basic rules of language propriety in speaking to others, especially to older adults. They claim that children walk past homes of people they know without greeting an acquaintance sitting on the porch or working on the lawn. Young males are particularly criticized for greeting others quickly in an incomprehensible and inarticulate manner.

CUISINE

Creole cooking is the distinguishing feature of Creole homes. It can be as subtle as Oysters Rockefeller, as fragrantly explicit as a jambalaya, or as down to earth as a dish of red beans and rice. A Creole meal is a celebration, not just a means of addressing hunger pangs. Many of the dishes listed below are features of African-influenced Louisiana, that is, Creoles of color and black Creoles.

The Europeans who settled in New Orleans found not only the American Indians, whose file (the ground powder of the sassafras leaf) is the key ingredient of Creole gumbos, but also immense areas of inland waterways and estuaries alive with crayfish, shrimp, crab, and fish of many different varieties. Moreover, the swampland was full of game. The settlers used what they found and produced a cuisine based on good taste, experimentation, and spices. On the experimental side, it was in New Orleans that raw, hard liquor was transformed into the more sophisticated cocktail, and where the simple cup of coffee became café Brulot, a concoction spiced with cinnamon, cloves, and lemon peel and flambéed with cognac. The seasonings used are distinctive, but there is yet another essential ingredient—a heavy black iron skillet.

Such dexterity produced the many faceted family of gumbos. Gumbo is a soup or a stew, yet too unique to be classified as one or the other. It starts with a base of highly seasoned roux (a cooked blend of fat and flour used as a thickening agent), scallions, and herbs, which serves as a vehicle for oysters, crabs, shrimp, chicken, ham, various game, or combinations thereof. Oysters may be consumed raw (on the half-shell), sauteed and packed into hollowed-out French bread, or baked on the half-shell and served with various garnishes. Shrimp, crayfish, and crab are similarly starting points for the Creole cook who might have croquettes in mind, or a pie, or an omelette, or a stew.

DANCES AND SONGS

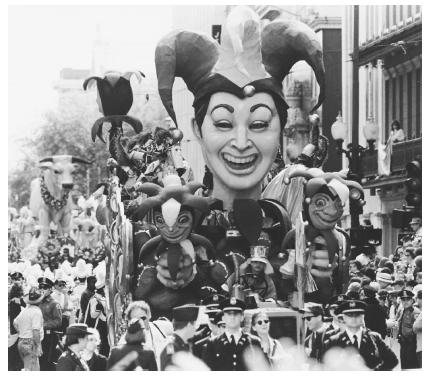

Creoles are a festive people who enjoy music and dancing. In New Orleans during French rule, public balls were held twice weekly and when the Spanish took over, the practice continued. These balls were frequented by white Creoles, although wealthy Creoles of Color may also have attended. Cotillions presented by numerous academies provided young ladies and gentlemen with the opportunity to display their skills in dancing quadrilles, valses à un temps, valses à deux temps, valses à trois temps, polkas, and polazurkas. Saturday night balls and dances were a universal institution in Creole country. The community knew about the dances by means of a flagpole denoting the site of the dance. Families arrived on horseback or in a variety of wheeled carriages. The older adults played vingt-et-un (Twenty-one) or other card games while the young danced and engaged in flirtations until the party dispersed near daybreak. During the special festive season, between New Year's and Mardi Gras, many brilliant balls were scheduled. Only the most respected families were asked to attend with lists scrutinized by older members of the families to keep less prominent people away

PROVERBS

A rich collection of Creole proverbs can be found in several references. One of the best is from Lafcadio Hearn's Gombo Zhebes, Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs (New Orleans: deBrun, n.d.): the monkey smothers its young one by hugging it too much; wait till the hare's in the pot before you talk; today drunk with fun, tomorrow the paddle; if you see your neighbor's beard on fire, water your own; shingles cover everything; when the oxen lift their tails in the air, look out for bad weather; fair words buy horses on credit; a good cock crows in any henhouse; what you lose in the fire, you will find in the ashes; when one sleeps, one doesn't think about eating; he who takes a partner takes a master; the coward lives a long time; conversation is the food of ears; it's only the shoes that know if the stockings have holes; the dog that yelps doesn't bite; threatened war doesn't kill many soldiers; a burnt cat dreads fire; an empty sack cannot stand up; good coffee and the Protestant religion were seldom if ever seen together; it takes four to prepare the perfect salad dressing—a miser to pour the vinegar, a spendthrift to add the olive oil, a

Language

The original language community of the Creoles was composed of French and Louisiana Creole. French was the language of white Creoles; it should not be confused with Louisiana Creole (LC). Morphologically and lexically Louisiana Creole resembles Saint-Domingue Creole, although there is evidence that Louisiana Creole was well established by the time Saint-Domingue refugees arrived in Louisiana. For many years, Louisiana Creole was predominantly a language of rural blacks in southern Louisiana. In the past, Louisiana Creole was also spoken by whites, including impoverished whites who worked alongside black slaves, as well as whites raised by black nannies.

French usage is no longer as widespread as it once was. As Americans from other states began to settle in Louisiana in large numbers after 1880, they became the dominant social group. As such, the local social groups were acculturated, and became bilingual. Eventually, however, the original language community of the Creoles, French and Louisiana Creole, began to be lost. At the end of the twentieth century, French is spoken only among the elderly, primarily in rural areas.

GREETINGS AND OTHER POPULAR EXPRESSIONS

The past sayings of the Creoles were unusual and colorful. According to Leonard V. Huber in "Reflections on the Colorful Customs of Latter-Day New Orleans Creoles," an ugly man who has a protruding jaw and lower lip had une gueule de benitier (a mouth like a holy water font), and his face was une figure de pomme cuite (a face like a baked apple). A man who stayed around the house constantly was referred to as un encadrement (doorframe). The expression pauvres diables (poor devils) was applied to poor individuals. Anyone who bragged too much was called un bableur (a hot air shooter). A person with thin legs had des jambes de manches-à-balais (broomstick legs). An amusing expression for a person who avoided work was that he had les cotes en long (vertical ribs). Additional Creole colloquialisms are: un tonnerre a la voile (an unruly person); menterie (lie or

Family and Community Dynamics

Traditionally, men were the heads of their household, while women dedicated their lives to home and family. The Creoles also felt it a duty to take widowed cousins and orphaned children of kinspeople into their families. Unmarried women relatives ( tantes ) lived in many households. They provided a much-needed extra pair of hands in running the household and rearing the children. Creoles today are still closely knit and tend to marry within the group. However, many are also moving into the greater community and losing their Creole ways.

WEDDINGS

In the old days, Creoles married within their own class. The young man faced the scrutiny of old aunts and cousins, who were the guardians and authorities of old family trees. The suitor had to ask a woman's father for his daughter's hand. The gift of a ring allowed them to be formally engaged. All meetings of young people were strictly chaperoned, even after the engagement. Weddings, usually held at the St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, were opulent affairs with Swiss Guards meeting the wedding guests and preceding them up the aisle. Behind the guests came the bride, accompanied by her father, and then the groom, escorting the bride's mother. The groom's parents followed, and then all the relatives of both bride and groom. A relative's absence was interpreted as a silent protest against the wedding. The bride's gown was handed down through generations or purchased in Paris to become an heirloom. Unlike today's weddings, there were no ring bearers, bridesmaids, or matrons of honor, or any floral decorations in the church. Ceremonies were held in the evenings. St. Louis Cathedral is still the place for New Orleans' Creole weddings, and many relatives still attend, though in fewer numbers.

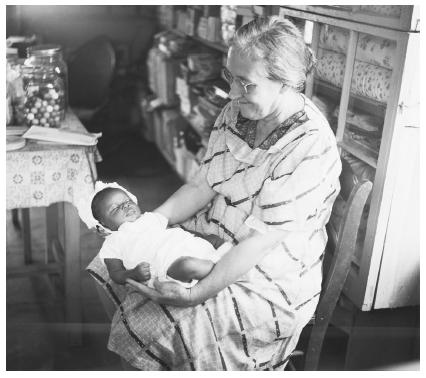

BAPTISMS

Baptisms usually took place when the child was about a month old. The godfather ( parrain ) and the god-mother ( marraine ) were always relatives, usually from each side of the family. It was a decided honor to be asked to serve as a godparent. The marraine gave the infant a gift of a gold cross and chain, and the parrain offered either a silver cup or a silver knife and fork. The godfather also gave a gift to the godmother and paid for the celebration that followed the baptism. It was an expensive honor to be chosen parrain.

FUNERALS

In the past, when someone died, each post in the Creole section of town bore a black-bordered announcement informing the public of the death and the time and place of the funeral. Usually the notices were put in the neighborhood where the dead person had lived, but if the deceased had wealth, notices would be placed all over the Vieux Carré. These notices were also placed at St. Louis Cathedral on a death notice blackboard. Invitations were issued for the funeral, and funeral services were held in the home.

The wearing of mourning was a rigorous requirement. The deceased's immediate family put on grand deuil (full mourning). During the six months of full mourning it was improper to wear jewelry or anything white or with colors. Men wore a black tie, a black crepe band on the hat, and sometimes a black band on the arm. After six months, the widow could wear black clothes edged with a white collar and cuffs. Slave or black Creole funeral processions often lasted an hour and covered a distance of less than six squares or one-third mile. News of the deaths were received through the underground route by a system of telegraph chanting.

Cemeteries held an important place in Creole life. A family tomb received almost as much attention as a church. To not visit the family tomb on All Saints' Day (November 1) was unforgivable. Some well-known cemeteries are St. Louis Number One, the oldest in Louisiana, and St. Louis Number Two. St. Roch Cemetery, which is noted for its shrine, was built by Father Thevis in fulfillment of a vow to Saint Roch for protection for the congregation of Holy Trinity Church from the yellow fever epidemic of 1868. Cypress Grove, Greenwood, and Metairie cemeteries are among the most beautiful burial grounds in Louisiana. Large structures resembling churches with niches for life-like marble statues of the saints may be found in Metairie Cemetery.

Religion

Roman Catholicism is strongly associated with Creoles. The French and Spanish cultures from which Creoles originate are so closely associated with Catholicism that some people assume that all Louisianians are Catholic and that all people in Louisiana are of French and/or Spanish ancestry. Records from churches in Mobile, New Orleans, and other parts of the area indicate the presence of both black and white Creoles in church congregations very early in the eighteenth century.

After segregation of the Catholic church in 1895, certain churches became identified with Creoles of color. In 1916 Corpus Christi Church opened in the seventh ward, within walking distance of many Creoles of color. St. Peter Claver, Epiphany, and Holy Redeemer are also associated with black populations. Each church has a parish school run by the Blessed Sacrament Sisters. St. Louis Cathedral and St. Augustine's Church are prominent in the larger Creole society, with women predominating in attendance. Today, only about half of the people in Louisiana are Catholics but the early dominance of Catholicism has left its mark on people of other denominations. In the southern part of the state, especially in New Orleans, place and street names are often associated with particular saints.

Almost all of the material written about Creoles describes a devotion to the Virgin Mary, All Saint's Day (November 1), and the many activities associated with the observance of Lent and Holy Week, especially Mardi Gras. Other important religious figures are St. Jude (the patron saint of impossible cases), St. Peter (who opens the gates of heaven), and St. Anthony (who helps locate lost articles).

Holy Week is closely observed by Creoles, both as a religious celebration and as a time of customs and superstition. On Holy Thursday morning, housewives, when they heard the ringing of church bells, used to take pots from the stove and place them on the floor, making the sign of the cross. Also, nine varieties of greens were cooked—a concoction known as gumbo shebes. On Good Friday Creoles visited churches on foot and in silence to bring good fortune.

Few Protestants and no known Jews are found in the white Creole community. Today, many Creoles are nonpracticing Catholics with some agnostics, some atheists, and a very few professing a non-Catholic faith.

Employment and Economic Traditions

The Creoles' image of economic independence is rooted in the socioeconomic conditions of free people of color before the Civil War. Creoles of color were slave owners, land owners, and skilled laborers. Of the 1,834 free Negro heads of households in New Orleans in 1830, 752 owned at least one slave. New Orleans persons of color were far wealthier, more secure, and more established than blacks elsewhere in Louisiana.

Economic independence is highly valued in the colored Creole community. Being on welfare is a source of embarrassment, and many of those who receive government aid eventually drop out of the community. African Americans with steady jobs, respectable professions, or financial independence frequently marry into the community and become Creole, at least by association.

Creoles of color and black Creoles have been quick to adapt strategies that maintain their elite status throughout changing economic conditions. Most significant is the push to acquire higher education. Accelerated education has allowed Creoles to move into New Orleans' more prestigious neighborhoods, first to Gentilly, then to Pontchartrain Park, and more recently to New Orleans East.

Politics and Government

When the Constitutional Convention of 1811 met at New Orleans, 26 of its 43 members were Creoles. During the first few years of statehood, native Creoles were not particularly interested in national politics and the newly arrived Americans were far too busy securing an economic basis to seriously care much about political problems. Many Creoles were still suspicious of the American system and were prejudiced against it.

Until the election of 1834, the paramount issue in state elections was whether the candidate was Creole or Anglo-American. Throughout this period, many English-speaking Americans believed that Creoles were opposed to development and progress, while the Creoles considered other Americans radical in their political ideas. Since then, Creoles have actively participated in American politics; they have learned English to ease this process. In fact, Creoles of color have dominated New Orleans politics since the 1977 election of Ernest "Dutch" Morial as mayor. He was followed in office by Sidney Bartholemey and then by his son, Marc Morial.

MILITARY

During the War of 1812, many Creoles did not support the state militia. However, during the first session of Louisiana's first legislature in 1812, the legislature approved the formation of a corps of volunteers manned by Louisiana's free men of color. The Act of Incorporation specified that the colored militiamen were to be chosen from among the Creoles who had paid a state tax. Some slaves participated at the Battle of New Orleans, under General Andrew Jackson, and he awarded them their freedom for their valor. Many became known as "Free Jacks" because only the word "Free" and the first five letters of Jackson's signature, "Jacks," were legible.

Individual and Group Contributions

CHESS

In 1858 and 1859 Paul Morphy (1837-1884) was the unofficial but universally acknowledged chess champion of the world. While he is little known outside chess circles, more than 18 books have been written about Morphy and his chess strategies.

LITERATURE

Kate O'Flaherty Chopin (1851-1904) was born in St. Louis; her father was an Irish immigrant and her mother was descended from an old French Creole family in Missouri. In 1870 she married Oscar Chopin, a native of Louisiana, and moved there; after her husband's death, she began to write. Chopin's best-known works deal with Creoles; she also wrote short stories for children in The Youth's Companion. Bayou Folk (1894) and The Awakening (1899) are her most popular works. Armand Lanusse (1812-1867) was perhaps the earliest Creole of color to write and publish poetry. Born in New Orleans to French Creole parents, he was a conscripted Confederate soldier during the Civil War. After the war, he was principal of the Catholic School for Indigent Orphans of Color. There he, along with 17 others, produced an anthology of Negro poetry, Les Cenelles.

MILITARY

Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (1818-1893), is perhaps the best known Louisiana Creole. He was born in New Orleans, educated in New York (unusual for the time), graduated from West Point Military Academy, and served with General Scott in the War with Mexico (1846). Beauregard was twice wounded in that conflict. He served as chief engineer in the draining of the site of New Orleans from 1858 to 1861. He was also a Confederate General in the Civil War and led the siege of Ft. Sumter in 1861. After the Civil War, Beauregard returned to New Orleans where he later wrote three books on the Civil War. He was elected Superintendent of West Point in 1869.

MUSIC

Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869), was a pianist and composer born in New Orleans. His mother, Aimée Marie de Brusle, was a Creole whose family had come from Saint-Dominique. Moreau went to Paris at age 13 to study music. He became a great success in Europe at an early age and spent most of his time performing in concerts to support members of his family. His best known compositions are "Last Hope," "Tremolo Etudes," and "Bamboula." Gottschalk is remembered as a true Creole, thinking and composing in French. An important figure in the history and development of American jazz, "Jelly Roll" Ferdinand Joseph Lementhe Morton (1885-1941), was a jazz musician and composer born in New Orleans to Creole parents. As a child, he was greatly influenced by performances at the French Opera House. Morton later played piano in Storyville's brothels; these, too, provided material for his compositions. His most popular works are "New Orleans Blues," "King Porter Stomp," and "Jelly Roll Blues."

Media

The Alexandria News Weekly.

Founded in 1975, this general newspaper for the African American community contains frequent articles about Creoles.

Contact: Rev. C. J. Bell, Editor.

Address: 1746 Wilson, Alexandria, Louisiana 71301.

Telephone: (318) 443-7664.

Bayou Talk.

A Cajun Creole newspaper.

Address: Jo-Val, Inc., Box 1344, West Covina, California 91793-1344.

Louisiana Weekly.

Black community newspaper published since 1925, which contains frequent articles about Creoles.

Contact: C. C. Dejoie, Jr., Publisher.

Address: 616 Barone Street, New Orleans, Louisiana 70150.

Telephone: (504) 524-5563.

The Times of Acadiana.

A weekly newspaper with Acadian/Creole emphasis.

Address: P.O. Box 3528, Lafayette, Louisiana 70502.

Telephone: (318) 237-3560.

RADIO

KAOK-AM.

Ethnic programs featuring Cajun and Zydeco music.

Contact: Ed Prendergast.

Address: 801 Columbia Southern Road, Westlake, Louisiana 70669.

Telephone: (318) 882-0243.

KVOL-AM/FM.

Features a weekly Creole broadcast with African American programming, news, and Zydeco music.

Contact: Roger Canvaness.

Address: 123 East Main Street, Alexandria, Louisiana 70501.

Telephone: (318) 233-1330.

Organizations and Associations

Creole American Genealogical Society (CAGS).

Formerly Creole Ethnic Association. Founded in 1983, CAGS is a Creole organization which promotes Creole American genealogical research. It provides family trees and makes available to its members books and archival material. Holds an annual convention.

Contact: P. Fontaine, Executive Director.

Address: P.O. Box 3215, Church Street Station, New York, New York 10008.

Museums and Research Centers

Amistad Research Center.

Independent, nonprofit research library, archive, and museum established by the American Missionary Association and six of its affiliated colleges. Collects primary source materials pertaining to the history and arts of American ethnic groups, including a substantial collection regarding Creoles.

Contact: Dr. Donald E. DeVore, Director.

Address: Tulane University, 6823 St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118.

Telephone: (504) 865-5535.

Fax: (504) 865-5580.

E-mail: amistad@mailhost.tcs.tulane.edu.

Online: http://www.arc.tulane.edu .

Bayou Folk Museum.

Collects furniture, furnishings, and artifacts relating to the educational, religious, social, and economic life of Creoles. Contains agricultural tools, doctor's office with instruments, and a blacksmith shop. Guided tours, lectures for study groups, and permanent exhibits.

Contact: Marion Nelson or Maxine Southerland.

Address: P.O. Box 2248, Natchitoches, Louisiana 71457.

Telephone: (318) 352-2994.

Beau Fort Plantation Home.

Collects Louisiana Creole period furnishings, furniture, and ornaments for display in a 1790 Creole house.

Contact: Jack O. Brittain, David Hooper, or Janet LaCour.

Address: P.O. Box 2300, Natchitoches, Louisiana 71457.

Telephone: (318) 352-9580.

Creole Institute.

Studies include Haitian and linguistic and related educational issues, and French-based Creoles.

Contact: Albert Valdman, Director.

Address: Indiana University, Ballantine 604, Bloomington, Indiana 47405.

Telephone: (812) 855-4988.

Fax: (812) 855-2386.

E-mail: mschowme@indiana.edu.

Online: http://php.indiana.edu/~valdman/creolehome.html> .

Louisiana State University.

Contains local history and exhibits, tools for various trades, and historic buildings. Conducts guided tours, provides lectures, and has an organized education program.

Contact: John E. Dutton.

Address: 6200 Burden Lane, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70808.

Telephone: (504) 765-2437.

Sources for Additional Study

Ancelet, Barry Jane, Jay D. Edwards, and Glen Pitre. Cajun Country. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1991.

Brasseaux, Carl A., Keith P. Fontenot, and Claude F. Oubre. Creoles of Color in the Bayou Country. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Bryan, Violet Harrington. The Myth of New Orleans in Literature: Dialogues of Race and Gender. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993.

Creoles of Color of the Gulf South, edited by James H. Dormon. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

Davis, Edwin Adams. Louisiana: A Narrative History. Baton Rouge: Claitor's Book Store, 1965.

Dominguez, Virginia R. White by Definition: Social Classification in Creole Louisiana. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Dormon, James H. "Louisiana's 'Creoles of Color': Ethnicity, Marginality, and Identity," Social Science Quarterly 73, No. 3, 1992: 615-623.

Eaton, Clement. A History of the Old South: The Emergence of a Reluctant Nation, third edition. New York: Macmillan, 1975.

Ebeyer, Pierre Paul. Paramours of the Creoles. New Orleans: Molenaar Printing, 1944.

Fiehrer, Thomas. "From La Tortue to La Louisiane: An Unfathomed Legacy," in The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Dominique Refugees, 1792-1809, edited by Carl A. Brasseaux and Glenn R. Conrad. Lafayette, Louisiana: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1992; 1-30.

Gehman, Mary. The Free People of Color of New Orleans: An Introduction. New Orleans: Margaret Media, Inc., 1994.

Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization, edited by Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Huber, Leonard V. "Reflections on the Colorful Customs of Latter-day New Orleans Creoles," Louisiana History, 21, No. 2, 1980; 223-235.

Kniffin, Fred B. Louisiana: Its Land and People. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1968.

Thank You

Nicole Foster

The family name Prendergast is still known around the Carribean,thanks to a famous singer Bob Marley,whose family now is joined to the Prendergast.This of course isn't the only connection,there are others all equally important to me and if any should read this,God Bless and guide you all the days of your life

Idid long ago see a local university article on them but 'puter crash'lost it all.

thank you for the pleasure of your company.

Thanks.

You are both correct in these respects. Mobile was settled before New Orleans and therefore Mardi Gras did orginate from Mobile. RBG is correct in that Creole is a culture and as in fact this article states, Creoles originally were identified as being of French and Spanish descent. I am a descendant of Julia Villars and Josef Colin. Julia was French Creole her father being Claude Durbieul de Villars of Dijon Provence, France. Josef was French, born in Portiers, France. Julia was born in 1732 making her one of the earliest French Creoles in the New World. While most of my ancestors were buried on Non Luis Island and many lived there, Julia Villars was quite wealthy and lived and died in Mobile. There are Creoles identified in many other countries: Brazil, Portugal, the Caribbean and others. Hence, the Creoles of color connotation although not all have necessarily black or African heritage. Primarily what Creoles share whether white Creole or Creoles of color is culture, language, food and religion.

people! I Was familiar with the zydeco band Rosie Ledet herself a Creole out of LA who's band member gave me a warm shoutout from the stage acknowledging a Creole girl! Lol! The one thing I found disturbing was that non Creole people when asked did they understand where zydeco came from

couldn't in the least bit tell u that it originated out of Creole culture! This just made me once again think of how a peoples culture can truly go unrecognized! The acknowledging of ones culture is a matter of respect! THIS IS A CONTIUOUS PROBLEM IN AMERICAN CULTURE!

ery good artical. Very informative. I am