Tlingit

by Diane E. Benson ('Lxeis')

Overview

Alaska is a huge land mass that contains many different environments ranging from the frigid streams and tundra above the Arctic circle to the windy islands of the Aleutians to the mild rainy weather of southeast Alaska. Alaska consists of over 533,000 square miles, with a coastline as long that of the rest of the continental United States. The southern end of the Alaska coastline, a region known as Southeast Alaska, is home to the primary Tlingit (pronounced "klingit") communities. This area covers the narrow coastal strip of the continental shore along British Columbia; it is similar in size and shape to the state of Florida, but with few communities connected by road. Tlingit communities are located from just south of Ketchikan and are scattered northward across islands and mainland as far as the Icy Bay area. Tlingit people also occupy some inland area on the Canadian side of the border in British Columbia and the Yukon Territory. The mainland Tlingit of Alaska occupy a range of mountains from 50 to 100 miles inland. The northern portion of Tlingit country is glacial with the majesty of the Fairweather and Saint Elias mountains overlooking the northern shores of the Gulf of Alaska. Fjords, mountains that dive into the sea, islands, and ancient trees make up most of this wet country that is part of one of the largest temperate rain forests in the world.

The total population of Alaska is just under 600,000. Approximately 86,000 Alaska Natives, the indigenous peoples of Alaska, live there. The Tlingit population at time of contact by Europeans is estimated to have been 15,000. Some reports include the Haida in population estimates, since Tlingit and Haida are almost always grouped together for statistical purposes. Today, Tlingit and Haida Central Council tribal enrollment figures show a total of 20,713 Tlingit and Haida, of which 16,771 are Tlingit. Most of the Tlingit population live in urban communities of southeastern Alaska, though a significant number have made their homes all across the continent. Euro-Americans dominate the Southeast population, with the Tlingit people being the largest minority group in the region.

EARLY HISTORY

The name Tlingit essentially means human beings. The word was originally used simply to distinguish a human being from an animal, since Tlingits believed that there was little difference between humans and animals. Over time the word came to be a national name. It is speculated that human occupation of southeast Alaska occurred 11,000 years ago by Tlingit people. Haida people, with whom the Tlingit have frequent interaction, have only been in the area about 200 years, and the Tsimpsian migrated only recently from the Canadian interior mainland.

Tlingit legends speak of migrations into the area from several possible directions, either from the north as a possible result of the Bering Sea land bridge, or from the southwest, after a maritime journey from the Polynesian islands across the Pacific. Oral traditions hold that the Tlingit came from the head of the rivers. As one story goes, Nass-aa-geyeil' (Raven from the head of the Nass River) brought light and stars and moon to the world. The Tlingit are unique and unrelated to other tribes around them. They have no linguistic relationship to any other language except for a vague similarity to the Athabaskan language. They also share some cultural similarity with the Athabaskan, with whom the Tlingit have interacted and traded for centuries. There may also be a connection between the Haida and the Tlingit, but this issue is debated. Essentially, the origin of the Tlingit is unknown.

Tlingit people are grouped and divided into units called kwan. Some anthropological accounts estimate that 15 to 20 kwan existed at the time of European contact. A kwan was a group of people who lived in a mutual area, shared residence, intermarried, and lived in peace. Communities containing a Tlingit population may be called the Sitkakwan, the Taku-kwan, or the Heenya-kwan, depending on their social ties and/or location. Most of the urban communities of Southeast Alaska occupy the sites of many of the traditional kwan communities. Before the arrival of explorers and settlers, groups of Tlingit people would travel by canoe through treacherous waters for hundreds of miles to engage in war, attend ceremonies, trade, or marry.

Through trade with other tribes as far south as the Olympic Peninsula and even northern California, the Tlingit people had established sophisticated skills. In the mid-1700s, the Spaniards and the British, attracted by the fur trade, penetrated the Northwest via the Juan de Fuca Islands (in the Nootka Sound area). The Russians, also in search of furs, invaded the Aleutian Islands and moved throughout the southwestern coast of Alaska toward Tlingit country. The Tlingit traders may have heard stories of these strangers coming but took little heed.

FIRST CONTACT WITH EUROPEANS

Europeans arrived in Tlingit country for the first time in 1741, when Russian explorer Aleksey Chirikov sent a boatload of men to land for water near the modern site of Sitka. When the group did not return for several days, he sent another boat of men to shore; they also did not return. Thereafter, contact with Tlingit people was limited until well into the 1800s.

Russian invaders subdued the Aleut people, and moving southward, began their occupation of Tlingit country. Having monopolized trade routes in any direction from or to Southeast Alaska, the Tlingit people engaged in somewhat friendly but profitable trading with the newcomers until the Russians became more aggressive in their attempts to colonize and control trade routes. In 1802 Chief Katlian of the Kiksadi Tlingit of the Sitka area successfully led his warriors against the Russians, who had set up a fort in Sitka with the limited permission of the Tlingit. Eventually the Russians recaptured Sitka and maintained a base they called New Archangel, but they had little contact with the Sitka clans. For years the Tlingit resisted occupation and the use of their trade routes by outsiders. In 1854 a Chilkat Tlingit war party travelled hundreds of miles into the interior and destroyed a Hudson Bay Company post in the Yukon Valley.

Eventually, diseases and other hardships took their toll on the Tlingit people, making them more vulnerable. In a period between 1836 and 1840, it is estimated that one-half of the Tlingit people at or

THE LAND CLAIMS PERIOD

The Treaty of Cession (1867) referred to indigenous people of Alaska as "uncivilized tribes." Such designation in legislation and other agreements caused Alaska Natives to be subject to the same regulations and policies as American Indians in the United States. Statements by the Office of the Solicitor in the U.S. Department of Interior in 1932 further supported the federal government's treatment of Alaska Natives as American Indians. As a result, Tlingit people were subject to such policies as the 1884 First Organic Act, which affected their claims to land and settlements, and the 1885 Major Crimes Act, which was intended to strip tribes of their right to deal with criminal matters according to traditional customs. By the turn of the century, the Tlingit people were threatened politically, territorially, culturally, and socially.

In response, the Tlingit people organized the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB). The ANB was founded in Sitka in 1912 by nine Tlingit and one Tsimpsian. The ANB's goals were to gain equality for the Native people of Southeast Alaska and to obtain for them the same citizenship and education rights as non-Natives. In 1915, due to the efforts of the ANB (and the newly organized Alaska Native Sisterhood), the territorial legislature adopted a position similar to the Dawes Act to allow Natives to become citizens, provided that the Natives became "civilized" by rejecting certain tribal customs and relationships. As a result, few Native people became citizens at this time; most did not become American citizens until the U.S. Congress adopted the Citizenship Act of 1924.

Tlingit people also actively pursued the right to vote. Unlike many Alaska Native people at the time who wanted to continue living as they had for many generations, Tlingit leaders sought increased political power. In 1924, William Paul, a Tlingit, won election to the Territorial House of Representatives, marking the beginning of a trend toward Native political power.

In 1929 the ANB began discussing land issues, and as a result Congress passed a law in 1935 allowing Tlingits and Haidas to sue the United States for the loss of their lands. By this time large sections of Tlingit country had become the Tongass National Forest. Glacier Bay had become a National Monument, and further south in Tlingit country, Annette Island was set aside as a reservation for Tsimpsian Indians from Canada. In 1959—the same year that Alaska was admitted as a state—the Court of Claims decided in favor of the Tlingit and Haida for payment of land that was taken from them. The Tlingit-Haida land claims involved 16 million acres without a defined monetary value; an actual settlement took years to conclude. In 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was passed, which called for the settlement of all claims against the United States and the state of Alaska that are based on aboriginal right, title, use, or occupancy of land or water areas in Alaska.

Tlingit individuals did not receive title to lands as a result of ANCSA. Instead, lands claimed by southeast Natives under this act were placed under the control of the ANCSA-established regional corporation, Sealaska, and the ANCSA-established village corporations. Some village corporations had the option to provide individuals with land in some cases, but most villages designated the land for future development.

The Native Allotment Act of 1906 did result in some Tlingit lands being placed in the hands of individual Tlingits. This law provided for conveyance of 160 acres to adult Natives as long as no tract of ground contained mineral deposits. Only a few allotments were issued in southeast Alaska. The Native Townsite Act of 1926 also provided only for the conveyance of "restricted" title lands, meaning such property could not be sold or leased without the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. Despite these gains, lands re-obtained this way by the villages or by individuals failed to sufficiently meet the needs of a hunting and fishing people.

The issues of Native citizenship, their right to vote, fishing and fishing trap disputes, and the activities of ANCSA contributed to the rising tensions between the Tlingit and the newcomers. In the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, it was not uncommon to see signs that read "No Indians Allowed" on the doors of business establishments. The Alaska Native Brotherhood did much to fight these prejudices and elevate the social status of the Tlingit and Haida people as American citizens. Today, although Tlingit people are much more accepted, their fight for survival continues. Their ability to subsist off the land and sea is constantly endangered by logging, pulp mills, overharvesting of the waters by commercial fisheries, government regulations, and the area's increasing population.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Throughout the nineteenth century, many Tlingit communities were affected by the influx of various industries. Fish canneries were established in Sitka and Klawock, gold mining began at Windham Bay, and a Presbyterian mission station was constructed at the place now known as Haines. New settlements like Juneau (1880) and Ketchikan (1888) dramatically changed Tlingit lands and economic systems. A mixed cash-subsistence economy developed, changing traditional trade and material acquisition systems. Missionary schools determined to acculturate the Tlingit and other Alaska Natives instructed the Tlingit in English and American ways and denied the indigenous students access to their traditional language, foods, dances, songs, and healing methods. Although change was overwhelming and Americanization pervasive, Tlingit clan structures remained intact, and traditions survived in the original communities. At the turn of the century it was not uncommon for southeast factories to employ clan leaders to prevent disputes and keep order between their employees and the Native communities.

The destruction and death brought on by disease caused many to abandon their faith in the shaman and traditional healing by the turn of the century. Smallpox and other epidemics of the early nineteenth century recurred well into the twentieth century. A number of communities, including Dry Bay and Lituya Bay, were devastated in 1918 and thereafter by bouts of influenza. Important and culturally fundamental traditional gatherings, or potlatches, became almost nonexistent in Tlingit country during the tuberculosis epidemics of the 1900s. These epidemics caused hundreds of Tlingit and other southeast people to be institutionalized; many of those who fell victim to these diseases were subsequently buried in mass graves. Tlingit people turned to the churches for relief, and in the process many were given new names to replace their Tlingit names, an important basis of identity and status in Tlingit society. Demoralization and hopelessness ensued and worsened with the government-sponsored internment of Aleut people in Tlingit country during World War II. Some Tlingit families adopted Aleut children who had been orphaned as a result of widespread disease and intolerable living conditions.

When they were established, the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood accepted acculturation as a goal for their members, believing that the abandonment of cultural traditions was in the peoples' best interest. Their organizational structure, however, reflected a traditional form of government to manage tribal and clan operations. Social and clan interactions and relationships continue to exist to this day despite all outside influences and despite the marked adaptations of Tlingit people to American society. The relatively recent revival of dances, songs, potlatches, language, and stories has strengthened continuing clan interactions and identities.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

Tlingit people believe that all life is of equal value; plants, trees, birds, fish, animals, and human beings are all equally respected. Clans and Clan Houses have identifying crests; a clan is equally proud whether its crest is a killer whale or a snail. There are no recognized superior species. When any "crested" living being dies, homage is expected, and appropriate respects are paid. Today, some communities of the southeast are still very sensitive to this tradition.

Tlingit people do not tolerate misuse or misappropriation of their crests, names, songs, designs, stories, or other properties. Each crest has stories and songs associated with it that belong to the crest and thereby to its clan. Ownership recognition of these things among the Tlingit is profound. Almost a century ago, two clans began a dispute over who owned a particular crest. This conflict is discussed in detail in Frederica de Laguna's 1972 work, Under Mt. St. Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakatat Tlingit. The issue developed into a social, political, and legal battle that ensued for decades, and in many ways remains unresolved. Using a killer whale song, story, or crest design without acknowledging the owning clan or without its permission, for example, can be considered stealing. Crest ownership sometimes conflicts with American notions of public domain. This conflict, along with a growing interest by the general public in Tlingit art and culture, has raised concerns among the clans about how to protect their birthrights from distortion and acquisition.

Tlingits demand that respect be shown toward other individuals and clans. When a person feels insulted by another, payment must be made by the person or clan who was responsible for the insult, or a process performed to remove the damage publicly. If this does not happen, bad feelings persist, negatively affecting relationships between clans. In the old ways, if a Tlingit person was seriously harmed or murdered by another Tlingit person, the "eye for an eye" philosophy would determine punishment: someone from the opposing clan would have to die. Today, that philosophy is adapted to remain within legal boundaries. Criminal cases are tried strictly by American law, but the family of the perpetrator is subject to social ostracism. Payment by the perpetrator's clan to the harmed clan for the wrongdoing is also conceivable.

Many newcomers to Tlingit country, including some missionaries, erroneously reported that the Tlingit people worshipped totems, idolized animals or birds as gods, and held heathen rituals. As a result some religious leaders instructed their Native congregations to burn or destroy various elements of their art and culture, and a good deal of Tlingit heirlooms were destroyed in this way. These misconceptions undermined the complexity and power of Tlingit culture and society.

POTLATCHES

Potlatches are an integral part of Tlingit history and modern-day life. A potlatch is a giant feast that marks a time for showing respect, paying debts, and displaying wealth. Tlingit people give grandly at potlatches to raise their stature. The respect and honor held toward one's ancestry, name, house crest, and family, and the extent of one's wealth might determine how elaborate a potlatch would be; these ceremonies are not, however, forms of worship to any gods. Potlatches are given for various reasons and may be planned for years in advance. The most common potlatches given today are funeral potlatches, the 40-Day Party, memorial potlatches, adoption potlatches, naming potlatches, totem-pole-raising potlatches, and house- or lodge-building potlatches.

A person's death requires a three-stage potlatch process to properly attend to the deceased person's transfer to the spirit world or future life. The first potlatch includes the mourning and burial of the deceased, lasting from one to four days. George Emmons reports in his book The Tlingit Indians that this process traditionally took four to eight days. During this time, the body is prepared for cremation or burial (which is more common today). Attendees sing songs of grief; sometimes the family fasts. Feasts are prepared for guests of the opposite clan (see below for explanation of opposite clans); afterward the person is buried. During the second stage, a party is held for the deceased person's clan. The third stage, or memorial potlatch, which can take place at any time, usually occurs about a year later. The memorial potlatch is a ritual process of letting go emotionally of the deceased. It marks the final release of the deceased to their future life as well as the final mourning, speeches, and deceased person's clan's payments to the opposite clan. The conclusion of the potlatch is a celebration of life and happy stories and song.

Sometimes less elaborate potlatches are held to give names to youngsters, or to those who have earned a new or second name. Naming potlatches may be held in conjunction with a memorial potlatch, as can adoption potlatches. Adoption ceremonies are held for one or more individuals who have proven themselves to a clan by their long term commitment to a Tlingit family or community and who have become members of the clan. The new members receive gifts and names, and are obligated from that day forward to uphold the ways of that clan. For whatever reason potlatches are held, ceremony is ever present. Participants wear traditional dress, make painstaking preparations, give formal speeches in Tlingit and English, and observe proper Tlingit etiquette.

CUISINE

The traditional diet of the Tlingit people relies heavily on the sea. Fish, seal, seaweed, clams, cockles, gum boots (chitons—a shell fish), herring, eggs and salmon eggs, berries, and venison make up the primary foods of most Tlingit people. Fish, such as halibut, cod, herring, and primarily salmon, (king, reds, silver, and sockeye) are prepared in many forms—most commonly smoked, dried, baked, roasted, or boiled. Dog, silver, humpy, and sockeye salmon are the fish best utilized for smoking and drying. The drying process takes about a week and involves several stages of cleaning, deboning, and cutting strips and hanging the fish usually near an open fire until firm. These strips serve as a food source throughout the year, as they are easily stored and carried.

The land of southeastern Alaska is abundant with ocean and wildlife, and because of this the Tlingit people could easily find and prepare foods in the warmer seasons, saving colder months for art, crafts, and elaborate gatherings. Today, although food sources have been impacted by population and industry, the traditional foods are still gathered and prepared in traditional ways as well as in new and creative ways influenced by the various ethnic groups who have immigrated into the area, especially Filipino (rice has become a staple of almost any Tlingit meal). Pilot bread, brought in by various seafaring merchants, is also common as it stores well, and softens, for the individual, the consumption of oil delicacies such as the eulochon and seal oils. Fry-bread is also an element of many meals and special occasions. Other influences on diet and food preparation besides standard American include Norwegian, Russian, and Chinese foods.

Other foods of the Tlingit include such pungent dishes as xákwl&NA;ee, soap berries (whipped berries often mixed with fish or seal oil), seal liver, dried seaweed, fermented fish eggs, abalone, grouse, crab, deer jerky, sea greens, - suktéitl&NA; —goose tongue (a plant food), rosehips, rhubarb, roots, yaana.eit (wild celery), and s&NA;ikshaldéen (Hudson Bay tea).

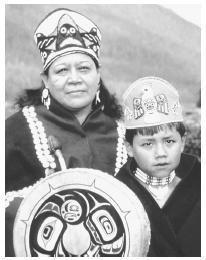

TRADITIONAL GARMENTS AND REGALIA

Traditionally Tlingit men and women wore loincloths and skirts made of cedar bark. Because of the rainy weather in southeastern Alaska, raincoats were worn, which were also made from natural elements such as spruce root or cedar bark. Today, Tlingit people no longer wear loincloths and cedar bark skirts, dressing very much as other contemporary Americans. Although modern, Tlingit people display their clan or family emblem on clothing or through jewelry, as has been the custom for centuries.

The most distinctive form of ceremonial dress prior to Americanization and still the most admired is the Chilkat robe. Although called the Chilkat robe after the Chilkat tribe of Tlingit who specialized in weaving, its origin is Tsimpsian. The robe is made from mountain goat wool and cedar bark strips and generally exhibits an emblem of the clan. This garment takes a weaver one to five years to make. The technique not only involves a horizontal weaving similar to that found in other cultures, but also a symmetrical and circular (curvilinear) design as well. This complex art form came dangerously close to extinction in the twentieth century, but through the perseverance of individuals in and outside the tribe there are now several weavers, elder and younger, in Tlingit and other northwest nations today. This is also true of the recently revived art of the Raven's Tail robe, another complexly woven garment of black and white worn over the shoulders in the same cape fashion as the Chilkat robe. Raven's Tail weaving of geometric and herring bone patterns is a skill that had not been practiced in nearly two centuries, but with the resurgence of cultural interest is now being practiced throughout the

In 1982 the Sealaska Heritage Foundation in Juneau began what is called Celebration. It occurs every even year as a gathering to celebrate culture. At Celebration today, many Chilkat robes can be seen. Chilkat robes are never worn as daily dress, but are worn with pride at potlatches, celebrations, and sometimes for burial, if the person was of a particular social stature. Chilkat robes are a sign of wealth, and traditionally if one owned such an item, he was generally a clan leader of great prestige. Giving away a Chilkat robe meant greater glory since only the wealthiest could afford to be so generous.

Modern regalia today consists primarily of the button blanket, or dancing robe, which although time consuming and expensive to make, is much more available to the people than the Chilkat or Raven's Tail robe. Russian influence played a great part in the evolution of the button blanket, since trade provided the Tlingit people with felt of usually red, black, or blue from which the button blanket is made. These robes are often intricately decorated with one's clan emblems through appliqué variations and mother of pearl (shell) button outlines or solid beading of the design. These robes are worn to display one's lineage and family crest at gatherings, in much the same way as the Chilkat robe.

Robes of any type are almost always worn with an appropriate headdress. Headdresses can be as varied and simple as a headband or as intricate and rich as a carved cedar potlatch hat, displaying one's crest, decorated with color, inlaid with abalone shell, and finished with ermine. Russian influence inspired the sailor style hat that many women wear for dancing. These are made of the same felt as the button blanket and completed with beaded tassels. Ornamentation traditionally included some hair dressing, ear and nose piercing, labrets, bracelets, face painting, and tattooing. Most of these facets of adornment are practiced today, excluding the labret.

The formal dress of the Tlingit people is not only a show of power, wealth, or even lineage, but is an integral part of the social practices of the Tlingit. Tlingit people practice the respect of honoring the opposite clan and honoring one's ancestors in the making and handling of a garment. Importance is placed also on the maker of the garment, and the relationship of his or her clan to the clan of the wearer. Dress in Tlingit culture is an acknowledgment of all who came before.

HEALTH ISSUES

Existing traditional health-care centers consist primarily of physical healing through diet and local medicines, although this practice is rather limited. A few people today still use teas brewed from the devil's club, Hudson bay tea leaves, roots, leaves, and flowers of various plants that cleanse the body, boost the immune system, and even heal wounds and illnesses. Overall, the Tlingit people primarily use modern medical treatment through the existing federally established health-care systems.

Contemporary health-care methods are only marginally effective. Some of the Tlingit believe that people have a relationships with spirits, can communicate with animals and birds, and can learn from all life forms. Those who vocalize these experiences or abilities, however, feel vulnerable about being labelled as mentally ill. Still considered a radical idea by most modernized Tlingit and mental health specialists, this aspect of Tlingit culture is only now beginning to be discussed.

Health problems among the Tlingit are not much different than they are with other Alaska Native peoples. Extensive and continuous Indian Health Service data demonstrate their susceptibility to such illnesses as influenza, arthritis, hepatitis, cancer, and diabetes. Alcoholism is a more common disease that has taken its toll on the people, and although suicide is not as high amongst the Tlingit as it seems to be in more northern Native communities, it too has caused havoc and despair for some Tlingit communities. Providing social and emotional support for individuals as well as for the family structure has become a concern for health-care professionals and concerned tribal citizens. Since the Alaska Natives Commission's 1994 report was released stressing the link between health and culture, more and more communities are discussing the psychology of various forms of cultural and social oppression and how to recover spiritually, mentally, and physically.

Language

The Tlingit language is a tone language that has 24 sounds not found in English. Tlingit is phonemic in that the difference in meaning between words often depends entirely on tone. Much of the Tlingit language is guttural and some of the sounds are similar to that of German. Almost all Alaska Native languages have guttural or "back-in-the-mouth" sounds. Tlingit is unique in that it is not only guttural but has glottalized stops and a series of linguistically related sounds called glottalized fricatives. The sounds of Tlingit are difficult and varied and include not only the more familiar rolling and drawn out vowel sounds and deeper guttural sounds, but also pinched and air driven sounds with consonants which are "voiceless" (except for the "n" sound, as in "naa"). Many of the consonants have no English equivalents.

In the nineteenth century, the first attempts were made to communicate in Tlingit through writing. The Russian Orthodox Church through Bishop Innocent (Veniaminov) created the first alphabet for the Tlingit language and developed a Tlingit literacy program. The Orthodox Church supported bilingual education in its schools, but the Americans discouraged it, and ultimately sought to suppress the use of the language completely. It was not until the 1960s that a Native language literacy movement was resumed through the efforts of such linguists as Constantine Naish and Gillian Story. These linguists created the Tlingit alphabet that is more commonly used today.

Unlike the English alphabet of 26 letters, the Tlingit language has at least 32 consonants and eight vowels. The alphabet was created with not only the familiar lettering of English but also with periods, underlines on letters, and apostrophes to distinguish particular sounds. For example; the word yéil means Raven, and yéil' (with the apostrophe) means elderberry.

Tlingit grammar does not indicate concern with time, whereas English conveys some sense of time with almost any verb usage. Tlingit verbs may provide the information about an action's frequency or indicate the stopping or starting of an action. The grammatical and phonological features of the language make it a difficult one to learn if it has not been taught since birth, but it is not impossible. Unfortunately, due to past efforts to suppress the language there are not many young speakers, although the need to keep the language alive is crucial. The need to maintain indigenous languages is urgently stated in the 1994 Final Report of the Alaska Natives Commission: "At the core of many problems in the Alaska Native community are unhealed psychological and spiritual wounds and unresolved grief brought on by a century-long history of deaths by epidemics and cultural and political deprivation at others' hands; some of the more tragic consequences include the erosion of Native languages in which are couched the full cultural understanding, and the erosion of cultural values."

GREETINGS AND COMMON EXPRESSIONS

Tlingit people do not use such greetings as hello, good-bye, good afternoon, or good evening. Some common expressions are: Yoo xat duwasaakw —my name is; Gunalchéesh —Thank you; Yak'éi ixwsiteení —It's good to see you; Wáa sá iyatee —How are you (feeling?; Wa.éku.aa? —Where are you going?; and Haa kaa gaa kuwatee —It's good weather for us.

Family and Community Dynamics

Tlingit society is divided into two primary ("opposite") clans or moieties, subclans or clans, and houses. The moieties are Raven and Eagle, and all Tlingits are either Raven or Eagle by birthright. The structure is matrilineal, meaning each person is born with the moiety of their mother, which is typically the opposite of the father: If the mother is Eagle, then the father is Raven or vice versa. Traditionally moiety intramarriage was not allowed even if the two Ravens or two Eagles were not at all blood related. Today, although frowned upon, moiety intramarriage occasionally occurs without the social ostracizing of the past.

Clans exist under the Raven moiety and the Eagle moiety. Clans are a subdivision of the moieties; each has its own crest. A person can be Eagle and of the Killer Whale or Brown Bear Clan, or of several other existing clans; Ravens may be of the Frog Clan, Sea Tern Clan, Coho Clan, and so forth. Houses, or extended families, are subdivisions of the clans. Prior to contact houses would literally be houses or lodges in which members of that clan or family coexisted. Today houses are one of the ways in which Tlingit people identify themselves and their relationship to others. Some examples of houses include the Snail House, Brown Bear Den House, Owl House, Crescent Moon House, Coho House, and Thunderbird House.

Tlingits are born with specific and permanent clan identities. Today these identities and relationships are intact and still acknowledged by the tribe. Biological relationships are one part of the family and clan structure; the other is the reincarnate relationships. Tlingit social structures and relationships are also effected by the belief that all Tlingits are reincarnates of an ancestor. This aspect of Tlingit lineage is understood by the elders but is not as likely to be understood and acknowledged by the younger Tlingit, although clan conferences are being held to educate people about this complex social system.

In Tlingit society today, even though many Tlingits marry other Tlingits, there exists a great deal of interracial marriage, which has changed some of the dynamics of family and clan relationships. Many Tlingit people marry Euro-Americans, and a few marry into other races or other tribes. Some of the interracial families choose to move away from the Tlingit communities and from Tlingit life. Others live in the communities but do not participate in traditional Tlingit activities. A few of the non-Tlingit people intermarried with Tlingit become adopted by the opposite clan of their Tlingit spouse and thereby further their children's participation in Tlingit society.

Traditionally boys and girls were raised with a great deal of family and community support. The uncles and aunts of the children played a major role in the children's development into adulthood. Uncles and aunts often taught the children how to physically survive and participate in society, and anyone from the clan could conceivably reprimand or guide the child. Today the role of the aunts and uncles has diminished, but in the smaller and dominantly Tlingit communities some children are still raised this way. Most Tlingit children are raised in typical American one-family environments, and are instructed in American schools as are other American children. Tlingit people place a strong importance on education and many people go on to receive higher education degrees. Traditional education is usually found in dance groups, traditional survival camps, art camps, and Native education projects through the standard education systems.

Religion

Traditionally, spiritual acknowledgment was present in every aspect of the culture, and healing involved the belief that an ailing physical condition was a manifestation of a spiritual problem, invasion, or disturbance. In these cases, a specialist, or shaman- ixt', would be called in to combat spirit(s) yéiks, or the negative forces of a witch or "medicine man." Today, anyone addressing such spiritual forces does so quietly, and most people are silent on the subject. The Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1978, but to date has had little effect other than to provide some legal support for Tlingit potlatch and traditional burial practices.

Institutionalized religion, or places of worship, were not always a part of the traditional Tlingit way of life, although they are now. The Russian Orthodox and Presbyterian faiths have had the longest and most profound impact on Tlingit society and are well established in the Tlingit communities. Other religions have become popular in southeast Alaska, and a few Tlingit people are members of the Jehovah Witnesses, the Bahai's, and the fundamentalist Baptist churches.

Employment and Economic Traditions

The Tlingit economy at time of contact was a subsistence economy supported by intense trade. The cash economy and the American systems of ownership have altered the lifestyle of Tlingit people dramatically; however, many Tlingits have adapted successfully. Job seekers find occupations primarily in logging and forestry, fishing and the marine industry, tourism, and other business enterprises. Because of the emphasis on education, a significant number of Tlingit people work in professional positions as lawyers, health-care specialists, and educators. The Sealaska Corporation and village corporations created under ANCSA also provide some employment in blue collar work, office work, and corporate management. Not all positions within the corporations are held by Tlingit and Haida, as a large number of jobs are filled by non-Natives. The corporations provide dividends—the only ANCSA compensation families receive for land they have lost, but these are generally rather modest. Some of the village corporations have produced some hefty lump sum dividends out of timber sales and onetime sale of NOL's (net operating losses) sold to other corporations for tax purposes, but these windfalls are infrequent.

Since the ANCSA bill passed in 1971, differences in wealth distribution among the Tlingit have arisen that did not previously exist. Some of the Tlingit people are economically disadvantaged and have less opportunities today to rely on subsistence for survival. Welfare reliance has become an all-too-common reality for many families, while those in political and corporate positions seem to become more financially independent. As a result shareholder dissension has increased annually and become rather public.

Politics and Government

Tlingit and Haida people have been and continue to be very active in both community and clan politics and tribal governments as well as in state and city issues. Many Tlingits since the 1920s have won seats in the Territorial legislature, setting in motion Tlingit involvement in all aspects of politics and government. Tlingit activist and ANS leader Elizabeth Peratrovich made the plea for justice and equality regardless of race to the territorial legislature on February 8, 1945 that prompted the signing of an anti-discrimination bill. Her efforts as a civil rights leader became officially recognized by the State of Alaska in 1988 with the "Annual Elizabeth Peratrovich Day." She is the only person in Alaska to be so honored for political and social efforts.

The ANCSA-created corporations wield a great deal of political power, and Tlingit and Haida corporate officials are often courted by legislators and businessmen. The corporations are a strong lobby group in Alaska's capital since they not only control lands and assets but represent over 16,000 Tlingit and Haida shareholders. Tlingit people cast their individual ballots based on their own choices and results show they tend to support the Democratic party. Tlingit people running for office also tend to run on a Democratic ticket.

The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 provided the first real means for traditional Tlingit law to be practiced and recognized by American government. Since 1978 several tribal courts have been created and tribal judges placed. A very active tribal court exists in Sitka with Tlingit judges presiding over civil matters brought before the court. Tribal courts in Tlingit country are not yet active in determining criminal cases as might be found in other tribal courts of the continental United States, but tribal councils are considering such jurisdiction. Tribal councils and tribal courts are much more a part of the communities than they were 20 years ago, and many issues today are addressed and resolved by Tlingit communities at this level.

Although no statistics are immediately available, many Tlingit men have fought in the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam. Tlingit participation in the U.S. armed forces is common and generally supported by the families and their communities.

Individual and Group Contributions

In the twentieth century the Tlingit people have made many contributions. The following mentions some notable Tlingit Americans and their achievements:

ACADEMIA

Elaine Abraham (1929– ), bilingual educator, was the first Tlingit to enter the nursing profession. In her early years she cared for people on the Navajo reservation during a diphtheria epidemic, and in Alaska, patients of tuberculosis and diphtheria during a time when many indigenous tribes feared modern medicine. Thereafter she served in major hospital supervisory positions and initiated such health programs as the original Southeast Health Aid Program and the Alaska Board of Health (now called the Alaska Native Health Board). An outstanding educator, she began as assistant dean of students at Sheldon Jackson College and was appointed vice-president in 1972. In Fairbanks she cofounded the Alaska Native Language Center and went on to become Vice-President of Rural Education and Extension Centers (1975). Abraham also established the Native Student Services office for Native students while teaching the Tlingit language at the Anchorage Community College. Her work in student services and indigenous understanding continues as Director of Alaska Native Studies for the University of Alaska in Anchorage.

GOVERNMENT

Elizabeth Peratrovich (1911-1958), civil rights activist, is recognized by Alaskans for her contributions to the equal rights struggle in the state of Alaska. February 17 is celebrated as Elizabeth Peratrovich Day. She is also listed in the Alaska Women's Hall of Fame (1989) and honored annually by the Alaska Native Sisterhood (which she served as Grand Camp President) and by the Alaska Native Brotherhood. Roy Peratrovich (1910-1989), Elizabeth's husband, is also honored by the Alaska Native Brotherhood and other Alaskans for his dedication to bettering the education system and for actively promoting school and social integration. His efforts frequently involved satirical letters to the newspapers that stimulated controversy and debate.

William L. Paul (1885-1977) began as a law school graduate and practicing attorney and became the first Alaska Native and first Tlingit in Alaska's territorial House of Representatives. He contributed to equal rights, racial understanding, and settlement of land issues. Frank J. Peratrovich (1895-1984) received a University of Alaska honorary doctorate for public service, serving as the Mayor of Klawock and as a territorial legislator in the Alaska House and Senate. He was the first Alaska Native not only to serve in the Senate but also to become Senate President (1948).

Andrew P. Hope (1896-1968) was an active politician and contributed to the advancement of Tlingit people and social change. He was instrumental in the development of the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) and was one of Alaska's few Native legislators. Frank See (1915– ) from Hoonah was also a notable legislator, mayor, and businessman, as was Frank Johnson (1894-1982), a teacher, legislator, and lobbyist. Frank Price was also elected to the territorial legislature.

LITERATURE AND ORATORY

Nora Marks Dauenhauer (1927– ), poet, scholar, and linguist, has dedicated her work to the survival of the Tlingit language; she has stressed the importance of story in culture. Besides such published works in poetry as The Droning Shaman, she has edited a number of works with her husband, Richard Dauenhauer, including the bilingual editions of Tlingit oral literature, Haa Shuka, Our Ancestors: Tlingit Oral Narratives (1987), and Haa Tuwunaagu Yis, for Healing Our Spirit: Tlingit Oratory (1990). Together they have developed Tlingit language instruction materials, Beginning Tlingit (1976), the Tlingit Spelling Book (1984), and instructional audio tapes. She has written numerous papers on the subjects of Tlingit language oratory and culture, and she has co-authored many other articles. Another active writer is Andy Hope III, essayist, poet, and editor of Raven's Bones Journal.

Orators and storytellers in Tlingit history and within the society today are numerous, but some of the noteworthy include Amy Marvin/Kooteen (1912– ); Chookan Sháa, who also serves as song-leader and as a lead drummer for the Mt. Fairweather Dancers; Robert Zuboff/Shaadaax' (1893-1974) traditional storyteller and humorist; Johnny Jackson/Gooch Éesh (1893-1985), storyteller, singer, and orator; and Jessie Dalton/Naa Tlaa (1903– ), an influential bilingual orator. Another well-respected orator was Austin Hammond/ Daanawáak (1910-1993), a traditions bearer and activist. Hammond dedicated a song to the Tlingit people just before he died for use in traditional gatherings and ceremony as the Tlingit national anthem.

PERFORMANCE AND DANCE

A widespread interest in Tlingit dancing, singing, and stories has generated the revival and development of a large number of traditional performance groups. The renowned Geisan Dancers of Haines have scheduled national and international engagements as have Kake's, Keex' Kwaan Dancers, and Sealaska Heritage Foundation's, NaaKahidi Theatre. Other major dance groups include the Noow Tlein Dancers of Sitka, led by Vida Davis, the acclaimed children's group, Gájaa Héen Dancers of Sitka, and the Mt. Fairweather Dancers (led for many years by the late T'akdeintaan matriarch, Katherine Mills). Other notable performance groups include the Tlingit and Haida Dancers of Anchorage, the Angoon Eagles, the Angoon Ravens, the Marks Trail Dancers, the Mt. Juneau Tlingit Dancers, the Mt. St. Elias Dancers, the Seetka Kwaan Dancers, the Killerwhale Clan, the Klukwan Chilkat Dancers, and the Klawock Heinya Dancers.

Gary Waid (1948– ), has bridged the Western stage and traditional performance for nearly two decades, performing nationally and internationally in such productions as Coyote Builds North America, (Perseverance Theatre, as a solo actor), and Fires on the Water (NaaKahidi Theatre, as a leading storyteller); he has also performed in educational films such as Shadow Walkers (Alaska State Department of Education and Sealaska Heritage Foundation). Besides performing regularly in Alaska and on tour, Waid performed in New York with Summer Faced Woman (1986) and Lilac and Flag (1994), a Perseverance Theatre Production coproduced with the Talking Band. He also performs Shakespeare and standard western repertoire. David Kadashan/Kaatyé (1893-1976) was an avid musician in both Tlingit and contemporary Western music during the big band era, and became a traditional orator and song leader of standing. Archie James Cavanaugh is a jazz musician and recording artist, best known for his album Black and White Raven (1980), with some selections recorded with the late great Native American jazz saxophonist, Jim Pepper.

VISUAL ARTS

Nathan Jackson is a master carver who has exhibited his works—totem poles, masks, bentwood boxes and house fronts—in New York, London, Chicago, Salt Lake City, and Seattle. His eagle frontlet is the first aspect of Native culture to greet airline passengers deplaning in Ketchikan. Two of his 40-foot totem poles decorate the entrance to the Centennial Building in Juneau, and other areas display his restoration and reproduction work. Reggie B. Peterson (1948– ) is a woodcarver, silversmith, and instructor of Northwest Coast art in Sitka, sharing his work with cultural centers and museums.

Jennie Thlunaut/Shax&NA;saani Kéek' (1890-1986), Kaagwaantaan, award-winning master Chilkat weaver, taught the ancient weaving style to others, and thereby kept the art alive. Jennie has woven over 50 robes and tunics, and received many honors and awards. In 1983 Alaska's Governor Sheffield named a day in her honor, but she chose to share the honor by naming her day Yanwaa Sháa Day to recognize her clanswomen. Emma Marks/Seigeigéi (1913– ), Lukaax.ádi, is also acclaimed for her award-winning beadwork. Esther Littlefield of Sitka has her beaded ceremonial robes, aprons, and dance shirts on display in lodges and museums, and a younger artist, Ernestine Hanlon of Hoonah creates, sells, and displays her intricate cedar and spruce basket weavings throughout southeast Alaska.

Sue Folletti/Shax&NA;saani Kéek' (named after Jenni Thlunaut) (1953-), Kaagwaantaan, silver carver, creates clan and story bracelets of silver and gold, traditionally designed earrings, and pendants that are sold and displayed in numerous art shows and were featured at the Smithsonian Institute during the Crossroads of the Continents traveling exhibit. Other exceptional Tlingit art craftsmen include Ed Kasko; master carver and silversmith from Klukwan, Louis Minard; master silversmith from Sitka; and developing artists like Norm Jackson, a silversmith and mask maker from Kake, and Odin Lonning (1953– ), carver, silversmith, and drum maker.

Media

Naa Kaani.

The Sealaska Heritage Foundation Newsletter; provides updates on Sealaska Heritage Foundations cultural and literary projects. English language only.

Address: 1 Sealaska Plaza, Suite 201, Juneau, Alaska 99801.

Raven's Bones Journal.

A literary newsletter; contains reports and essays on tribal and publication issues along with listings of Native American writers and publications. (English language only.)

Contact: Andy Hope III, Editor.

Address: 523 Fourth Street, Juneau, Alaska 99801.

Sealaska Shareholder Newsletter.

A bimonthly publication of the Sealaska Corporation. The primary focus is on corporate and shareholder issues, but also reports on Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimpsian achievements and celebrations. Each issue provides a calendar of cultural, corporate, and social events. (English language only.)

Contact: Vikki Mata, Director of Corporate Communications.

Address: 1 Sealaska Plaza, Suite 400, Juneau, Alaska 99801-1276.

Telephone: (907) 586-1827.

RADIO AND TELEVISION

KTOO-FM.

A local radio and television broadcast station; does a 15-minute Native report five mornings a week. "Raincountry," a weekly program on television deals with Native affairs in Alaska focusing on issues in Tlingit country and the southeast as a whole. On Mondays the station airs the "Alaska Native News," a half-hour program, and Ray Peck Jr., Tlingit, hosts a radio jazz show. No Tlingit person is otherwise on staff for these programs.

Contact: Scott Foster.

Address: 224 Fourth Street, Juneau, Alaska 99801.

Telephone: (907) 586-1670.

Organizations and Associations

Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB)/Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS).

ANB (founded in 1912) and ANS (founded in 1915) promote community, education, and justice through a governing grand camp and operating subordinate camps (local ANB and ANS groups). Native education and equal rights are some of the many issues addressed by the membership, as are Tlingit and Haida well being and social standing.

Contact: Ron Williams, President.

Address: 320 West Willoughby Avenue, Juneau, Alaska 99801.

Telephone: (907) 586-2049.

Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska (CCTHITA).

Founded in 1965. Provides trust services through Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to Tlingit and Haida people and Tlingit and Haida villages in land allotment cases, operates health and tribal employment programs, and issues educational grants and scholarships.

Contact: Edward Thomas, President.

Address: 320 West Willoughby Avenue, Suite 300, Juneau, Alaska 99801-9983.

Telephone: (907) 586-1432.

Organized Village of Kake.

Founded in 1947 under the Indian Reorganization Act. Contracts with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to provide services to the tribe such as counseling referral, general assistance, assistance in Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) issues, education and cultural development, scholarships, and housing improvement. Through a Johnson O'Malley BIA contract they provide supplemental education and culture/language classes. The organization also handles its own tribal land trust responsibilities.

Contact: Gary Williams, Executive Director; or, Henrich Kadake, President.

Address: P.O. Box 316, Kake, Alaska 99830.

Telephone: (907) 785-6471.

Sitka Tribe of Alaska (STA).

Chartered in 1938 under the Indian Reorganization Act as the Sitka Community Association, STA is a federally recognized tribe and operates contracts under the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). STA has an extensive social services program, providing counseling, crisis intervention, employment services, housing improvement, youth and education programs, economic development, and historic preservation. STA also supports a tribal court.

Contact: Ted Wright, General Manager; or, Larry Widmark, Tribal Chair.

Address: 456 Katlian Street, Sitka, Alaska 99835.

Telephone: (907) 747-3207.

Yakutat Native Association (YNA).

Founded in 1983. Provides family services to the tribe through Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) contracts. YNA's Johnson O'Malley program provides dance instruction, runs a culture camp in the summer, and is in the processes of developing a language program.

Contact: Nellie Valle.

Address: P.O. Box 418, Yakutat, Alaska 99689.

Telephone: (907) 784-3238.

Museums and Research Centers

Alaska State Museum.

Houses a varied collection of southeast Alaska Indian art, with elaborate displays of traditional Tlingit regalia, carvings, artifacts, and totem designs.

Address: 395 Whittier Street, Juneau, Alaska.

Telephone: (907) 465-2901.

Sheldon Jackson Museum.

Houses Tlingit regalia, a canoe, a large spruce root basket collection, and other traditional items and artifacts including house posts, hooks, woodworking tools, bentwood boxes, and armor. The museum also contains a large variety of Aleut and Eskimo art. The museum's gift shop sells baskets and other Tlingit art.

Address: 104 College Drive, Sitka, Alaska 99835.

Telephone: (907) 747-8981.

Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center.

Shares the history of Haines, the gold rush era, and Tlingit art in the displays. The center provides books and flyers on different aspects of Tlingit art and history, as well as live demonstrations in traditional crafts.

Address: P.O. Box 623, Haines, Alaska 99827.

Telephone: (907) 766-2366.

Southeast Alaska Indian Cultural Center.

Displays a model panorama of the Tlingit battles against the Russians in 1802 and 1804, elaborate carved house posts, and artifacts. The center shows historic films and has a large totem park outside the structure. Classes are conducted in Tlingit carving, silversmithing, and beadwork, and artists remain in-house to complete their own projects.

Address: 106 Metlakatla, Sitka, Alaska 99835.

Telephone: (907) 747-8061.

Totem Heritage Center.

Promotes Tlingit and Haida carving and traditional art forms and designs by firsthand instruction. The center maintains brochures and other information on artists in the area as well as instructional literature.

Address: City of Ketchikan, Museum Department, 629 Dock Street, Ketchikan, Alaska 99901.

Telephone: (907) 225-5600.

Sources for Additional Study

Case, David S. Alaska Natives and American Laws. University of Alaska Press, 1984.

Cole, Douglas. Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer. Haa Kusteeyí, Our Culture: Tlingit Life Stories. Seattle: University of Washington Press; and Juneau, Alaska: Sealaska Heritage Foundation, 1994.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer. Haa Tuwunáagu Yís, for Healing Our Spirit: Tlingit Oratory. Seattle: University of Washington Press; and Juneau, Alaska: Sealaska Heritage Foundation, 1990.

Emmons, George Thornton. The Tlingit Indians. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991.

Garfield, Viola E., and Linn A. Forrest. The Wolf and The Raven: Totem Poles of Southeastern Alaska. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993.

Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northern Tlingit. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press, 1986.

Langdon, Steve J. The Native People of Alaska. Anchorage, Alaska: Greatland Graphics, 1987.

Samuel, Cheryl. The Chilkat Dancing Blanket. Seattle: Pacific Search Press, 1982.

Steward, Hilary. Looking at Totem Poles. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993.

hello! Thank you for the page(s) awesome work,I learned lots,Still am...of courseI had to bookmark the page and read it incrementally..I hope all is well with you and yours..Roger,an old family friend from sitka.

Thanks again and aloha!

Charles

Does anybody know there is a tribe called Telenghed in Central Asia, particularly in my country Mongolia? I am an American Studies major student trying to do research about it. Not many books available here. Please help.

I am from Sitka, Alaska. I am of the Raven moity, I am raven choho.

I found wounderful information on this website. I learnd alot from here, as well as stuff that i've learnd from growing up with tradition all around me. I am apart of the Gajaa Heen Dance group, it is there and at Robby Littlefeilds camps along with home that I have learnd most about my tradions, language, gathering, and more. Traditions are always fun to learn, there are times to be serious and times to have fun; something the Tlingit people take seriously. The language is not easy to learn by book, and takes many times of practice as we do not here it around us all the time any more. It is something we are scared to lose, but are makeing ever effort we can as the Tlingit people to keep it around for ever other generation after ours. Every time we have communite gathering and Gajaa Heen Dancers or any dance group preforms you can see the beautiful smiles of all our elders; because in their heart they know songs and dance are still being done, and we thank them all out of respect when we are done, for listening and taking time to watch US. It is something we do! we dont think twice about respect. something we have been toght since a child. Respect is something that goes with everthing; including our food gathering, at the top of the website talks about how we rely on the ocean very much, and yes it is very acsessable from here (Sitka), but when we the Tlingit people havest anything it is out of respect we thank the animal or plant for giving its life to feed ours; and is strongly who we are. beleived long ago that if you dis respect a food given to us, it will do the same to us, and will slowly not be there to feed us. Over many years I learn and relearn things every day about my culure, and i would greatly like to thank the website for all the wounderful information i found on the page.

Gunaaxcheesh hoho Ax Xeit yeis aa' xei(thank very much you for listening to my words.)

My name is Frank Benson and I really loved your article. My family is from Mt. Edgecumbe/Sitka, I read that you too are from Sitka, and I cant help but think that perhaps we are related somehow. I knew very little about my father. I don't remember much about him, I met him only once, my grandparents were Mary and George. I'm sure there are many on the Benson side that I have never met. If you care to, please contact me at the email listed.

Thank you and have a great day.

Frank

My name is Grace and I am a student in Wyoming. I am writing an article about a subject in the Tlingit tribe. I chose to do a well-known author and chose you. While doing my research, I encountered some issues, such as the year of your birth seems to be uncertain. Almost an equivalent amount of resources say that your birth year is either 1954 or 1959. I would like be able to include accurate information in my article, and thought you would be the best person to clear up any misunderstandings. I hope you understand and know I appreciate your help very much.

If it’s of no inconvenience to you, I also have a few more questions:

1. When were you born?

2. More than once in my research, there has been the name ‘Lxeis’ by your name? What is ‘Lxeis’?

3. How would you describe your childhood?

4. How would you describe work on the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline?

5. What year did the Indian Girls poem controversy take place? How did this affect you at that time?

6. If possible, would you be interested in proof-reading my article to clear up any wrong information that I am unaware of including into my article?

Your answers will greatly help me in my research and writing and will also be immensely appreciated.

Sincerely,

Grace, a student in Wyoming

Thank YOU so much,

Reporter,

Kyra