Choctaws

by D. L. Birchfield

Overview

The Choctaw nation occupies several non-contiguous blocks of land east of the Mississippi River. Larger than Massachusetts, the land area is located primarily in east-central Mississippi, site of the Choctaw ancestral homeland, and in a large contiguous block of land west of the Mississippi River, where the majority of the Choctaws were moved in the early 1830s. Here, the nation takes in the southeast portion of Oklahoma that encompasses ten and one-half counties. Choctaw communities are also located in Louisiana and Alabama.

The Choctaw nation is divided into separate governmental jurisdictions, each operating under its own constitution. The largest of these, and the only two formally recognized by the U.S. government, are the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Other Choctaw groups, such as the Mowa Choctaws of Alabama, are seeking federal recognition. Since the United States proposed Article IV of the Treaty with the Choctaw in 1820, the official policy of the United States has been to attempt to abolish the Choctaw nation, confiscate its land, and assimilate its people. Article IV states that "the boundaries hereby established between the Choctaw Indians and the United States, on this side of the Mississippi river, shall remain without alteration until the period at which said nation shall become so civilized and enlightened as to be made citizens of the United States." By 1907, when Oklahoma achieved statehood, the federal government had adopted the position that the Choctaw nation had ceased to exist. Not until the present generation did the courts begin to uphold some of the Choctaw claims to national sovereignty. Making rulings about Choctaw claims has been complicated by competing claims of several state governments and those of the U.S. government.

CHOCTAW SOVEREIGNTY

During the 1890s and the first years of the twentieth century, the U.S. government forcibly moved the Choctaws and other Indian nations into the region that is now the state of Oklahoma. Each nation was forced to accept individual allotments from a tribal land base, their nations were dissolved, and they were forced to become citizens of the new state.

The Choctaw paid a high price to maintain sovereignty. In an 1820 treaty with the United States, the Choctaw acquired new land west of the Mississippi to replace the ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi from which they had been removed. The nation bargained for its right to security within its own government, on its own land in 1830, giving the U.S. government more than ten million acres of land—all of the nation's remaining land in Mississippi and Alabama—in exchange for that right.

In Article IV of the 1830 treaty with the Choctaw, the nation secured this guarantee from the U.S. government: "The Government and people of the United States are hereby obliged to secure to the said Choctaw Nation of Red People the jurisdiction and government of all the persons and property that may be within their limits west, so that no Territory or State shall ever have a right to pass laws for the government of the Choctaw Nation of Red People and their descendants; and that no part of the land granted them shall ever be embraced in any Territory or State."

Few Americans know about the treaty or its contents, and those who do are not eager to acknowledge it. The Oklahoma public education system, for example, does not include this aspect of the state's history in its public school curriculum. Prejudice against indigenous people runs high in Oklahoma, where its citizens do not like to be reminded that their state was founded upon land guaranteed to "Indians."

THE FIRST CHOCTAWS IN AMERICA

Choctaws are an ancient people, but by their own account, they were the last of earth's inhabits to appear. According to Choctaw belief, the first people to appear upon the earth lived a great distance from what would become the Choctaw homeland. These people emerged from deep beneath the earth's surface through a cave near the sacred mound, Nanih Waiya. They draped themselves on bushes around the cave to dry themselves in the sunshine, and then went to their distant homes. Many others followed the same pattern, finding homes closer and closer to the cave. Some of the last to emerge were the Cherokees, Creeks, Natchez, and others, who would become the Choctaw's closest neighbors. Finally, the Choctaws emerged and established their homeland around the sacred mound of Nanih Waiya, their mother.

Another Choctaw legend holds that they migrated to the site of Nanih Waiya after a great long journey from the northwest, led by a hopaii who carried a sacred pole that was planted in the ground each evening. Every morning the people continued their journey toward the rising sun, according to the direction in which the pole leaned. Finally, they awoke one morning to find the pole standing upright. They built Nanih Waiya on that site and made their home there.

In another version of the migration story, two brothers, Chahta and Chicksa, led the migration. After arriving at the site of Nanih Waiya, the group following Chicksa became lost for many years and became the Chickasaws, the Choctaws' nearest northern neighbors. Today, Nanih Waiya is a state park near the headwaters of the Pearl River in the east-central portion of Mississippi. "Mississippi," from the Choctaw word Misha sipokni, means "older than time," the Choctaw name for the great river of the North American continent.

It is not known whether there is a connection between the Choctaws, who have a great affection for the sacred mound of Nanih Waiya, and a mound-building civilization that flourished in North America about 2,000 years ago. This civilization constructed approximately 100,000 mounds in the greater Mississippi River Valley, some of which are among the most colossal structures of antiquity. The base of the Great Temple Mound at Cahokia, Illinois, for example, is three acres larger than the Great Pyramid of Egypt. Archaeologists believe Nanih Waiya was probably constructed around 500 B.C.

In the early eighteenth century the Natchez, one of the Choctaw's nearest neighbors, were still practicing a temple mound culture when Europeans first made intimate contact with Indians of that area. Many of the mounds were obliterated by farmers before they could be subjected to scientific study, and others were destroyed by eager amateurs. Remarkably, Americans have shown little interest in the mounds, limiting most exploration to hunting for pots.

In her doctoral dissertation on Choctaw history at the University of Oklahoma in 1934 (published as The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic ), historian Angie Debo attempted to summarize the characteristics of the ancient Choctaws: "They seem to have been distinguished for their peaceful character and their friendly disposition; their dependence on agriculture and trade; the absence of religious feeling and meaningful ceremonial; and their enjoyment of games and social gatherings. A mild, quiet, and kindly people, their institutions present little of spectacular interest; but to the very extent that they were practical minded and adaptable rather than strong and independent and fierce, they readily adopted the customs of the more advanced and more numerous race with which they came in contact."

BEFORE EUROPEAN CONTACT

The Choctaws were one of the great nations of the western hemisphere, with an estimated population of 20,000 people living in more than 100 agricultural centers. The Cherokees and the Creeks were of similar size. Choctaw territory encompassed more than 23 million acres in present day Mississippi as well as portions of Alabama and Louisiana.

Choctaws enjoyed the reputation of a peaceful, agricultural people. Their large numbers provided them with a measure of security from attack by their neighbors, and they are not known to have been disposed to seek military conquest. In fact, disputes among tribes in the region were sometimes settled by a game of ball. In one famous recorded instance, the Creeks and the Choctaws agreed to settle a disagreement about hunting rights to a watershed that lay between them based on the outcome of a game of ball. Tragically, the game ended in bloodshed and may have marked the last instance in which such disputes were decided in that manner. It is said that a Choctaw player became enraged and grabbed a weapon during play. When he attacked some of the Creek players, everyone took up their weapons. Many of the best players from both nations lay dead before elders could intervene. Because outbreaks of violence were unheard of in such games before this incident, it has been said that the Creeks and Choctaws were in shock that such an event could occur.

FIRST RECORDED CONTACT WITH EUROPEANS

The Choctaws entered European historical records when the Spaniards of Hernando De Soto's expedition encountered them in the 1540s—an unhappy encounter for both parties. DeSoto, who had been Francisco Pizarro's cavalry captain in Peru, came to the southeastern portion of North American seeking another civilization as rich in gold and silver as the Incas. When he demanded women and baggage carriers of chief Tuscaloosa at the Choctaw town of Moma Bina, a battle ensued, and the Spaniards' baggage train was burned in a fire that also destroyed Moma Bina. The armored Spanish war horses struck terror in the Choctaws, who had never seen horses before, and Choctaw losses in the battle were heavy. The Choctaws nonetheless inflicted a reported 644 arrow wounds on the Spaniards, piercing their skin wherever armor did not protect it. After a period of rest and recovery, DeSoto's expedition passed through Choctaw country without further incident and wintered among the Chickasaws, who trapped them in a fire so hot that the Spanish had to build a forge and re-temper the steel in their swords before crossing the Mississippi and leaving the lands of the southeastern Indians.

RELATIONS WITH THE COLONIZERS

Following the establishment of Louisiana in 1700, the Choctaws and the French became acquainted and maintained an amicable relationship until 1763, when the French were expelled from North America at the conclusion of the French and Indian War. The Choctaws were the pivotal Indian nation with whom the French had to maintain good relations for the security of the Louisiana colony. The French were helped immeasurably in this regard by the depredations of English slave raiders who operated out of the Carolinas and took thousands of Choctaws into slavery in the early eighteenth century.

Choctaw relations with other Indians in the region were greatly affected by the presence of the French. In the 1730s the French waged a war of extermination against the Natchez, close neighbors of the Choctaws. The surviving Natchez fled to the Chickasaws for protection, and the Choctaws were drawn into a war against the Chickasaws that would rage on and off until the French left Louisiana.

The Choctaws experienced the devastating Choctaw Civil War of 1747-1750 when the nation was divided between those who wanted to maintain trade relations exclusively with the French and those who wanted to enter into trade relations with the English. Along with the removal of the Choctaws to the west, the civil war ranks as one of the most catastrophic events in recorded Choctaw history. The war's depopulation of entire villages severely weakened the Choctaws. Eventually, they realized that only the European colonial powers benefited from this infighting and concluded a peace.

An argument about who was responsible for failing to adequately supply the English faction of the Choctaws has come down to us from the eighteenth century by people deeply involved in attempting to persuade the Choctaws to trade with the English. Among them are James Adair, the English trader among the Chickasaws, in the 1775 British publication History of the American Indians, and his one-time business partner Edmond Atkin, in "Historical Account of the Revolt of the Choctaw Indians," a 1753 manuscript in the British Museum.

After the French were expelled from North America in 1763, the Choctaws maintained relations with the British and Spanish, both of whom courted their allegiance. One result of the Choctaw Civil War was that the Choctaws became very cautious, skilled diplomats at dealing with European colonial powers, an attribute of Choctaw political life that would carry over to dealings with the Americans.

During the Revolutionary War, the Choctaws sided with the Americans, providing scouts for Generals Morgan, Sullivan, Wayne, and Washington, and in 1786, entered into their first formal treaty with the Americans—a treaty of peace and friendship. In their second treaty with the Choctaws in 1801, the Americans secured Choctaw permission to build a wagon road through the Choctaw nation. Shortly afterward, Americans began appearing in Choctaw country in increasing numbers and demanding land, by treaty, with a frequency that alarmed the Choctaws. In 1805, at the negotiations for the Treaty of Mount Dexter, the Americans began pressuring the Choctaws to accept President Thomas Jefferson's idea of removing themselves to new homes west of the Mississippi River.

Despite these pressures, the Choctaws maintained friendly relations with the United States. In 1811, the Choctaws expelled Tecumseh from their nation when he tried to enlist them in his Indian confederacy, and fought against the Red Stick faction of the Creeks in the ensuing war between the United States and the Creeks, who had chosen to join Tecumseh's alliance. The Choctaw war chief Pushmataha led 800 Choctaw troops, who became a part of General Andrew Jackson's army. Pushmataha also led Choctaw troops against the British in support of Jackson's army at the Battle of New Orleans. Despite Choctaw loyalty, the United States demanded further land cessions in 1816.

In 1820, the Choctaws finally agreed to trade a substantial portion of their land for a huge tract of land west of the Mississippi River; however, they retained more than ten million acres of their original homeland east of the Mississippi River and did not agree to remove themselves to the west. But in 1830, after Andrew Jackson had become president, the Choctaws were forced to cede the remaining land east of the Mississippi River in a treaty with the United States—also known as the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, or the Choctaw removal treaty—and remove as a nation to the West.

In Chief Pushmataha, American Patriot, published in 1959, historian Anna Lewis, revealed that General Andrew Jackson secured the signature of Chief Puckshenubbee, of the Okla Falaya Choctaw division, to the treaty of 1820 by means of blackmail. Puckshenubbee's daughter had married an American soldier who had deserted. When Jackson learned of this, he threatened to have Puckshenubbee's son-in-law shot if Puckshenubbee did not sign the treaty. The Americans candidly reported the blackmail to the U.S. State Department. The reports were preserved in the State Department files where Lewis eventually found them.

REMOVAL

The Choctaws were the first Indians to be removed as a nation by the U.S. government to new land in the West. For the most part, the removal was accomplished in three successive, brutal winter migrations during which 2,500 Choctaws died, many from exposure and starvation. In 1831, the newly created Bureau of Indian Affairs conducted the first removal. The government decided that the removal had been too costly, even though by the terms of the removal treaty the Choctaws were to pay the cost of removal out of profits from the sale of their lands in Mississippi. The U.S. Army was placed in charge of the 1832 and 1833 removals, they cut costs by severely reducing both rations and blankets. When the Choctaws ran out of food and attempted to purchase supplies, the citizens of Arkansas reacted by raising the price of corn. By 1834, 11,500 Choctaws had been removed to the west.

About 6,000 Choctaws remained in Mississippi where, by the terms of Article 14 of the removal treaty, they were to be allowed to choose individual land holdings of 640 acres for each head of household, 320 acres for children over the age of ten, and 160 acres for younger children; however, only 69 Choctaw heads of households were allowed to register for land in Mississippi. Finding themselves dispossessed of everything they owned, they became squatters in their former land. Many took to the swamps where they lived as furtive refugees until they were finally provided with a small reservation near Philadelphia, Mississippi, in the early twentieth century. Throughout the nineteenth century, Mississippi Choctaws continued to remove to the West, often at the urging of official Choctaw delegations sent from the West to induce them to join them.

CHOCTAW NATION

In 1820 (modified by the treaty of 1824) the Choctaws purchased from the United States what amounted to the southern half of the present day state of Oklahoma, an area that included at its western edge the very heartland of the Comanche nation. Upon their arrival in the West in 1834, the Choctaws immediately adopted a written constitution. The constitution was modified in 1837 when the Chickasaws once again became a part of the Choctaw nation, having been removed from their homeland and allowed to choose homes among the Choctaws. They were given a quarter of the votes in the Choctaw legislature. In 1855, the Chickasaws became a separate nation again, purchasing from the Choctaws what is today the central section of southern Oklahoma.

In the West the Choctaws soon recovered from the trauma of removal and established a republic that flourished for a generation. During this generation of peace and prosperity, the Choctaw nation built a stable economy, established its own public school system, governed itself under its own laws, and adopted many of the habits of its American neighbors.

The Choctaw remained largely free from the encroachments of the advancing American frontier until they were caught between warring Americans factions and drawn into the Civil War. At its outbreak, the Union removed its troops from Indian Territory, leaving the Choctaws defenseless. The Choctaw were surrounded by Confederates and held long-standing grievances against the United States. In addition, a small percentage of the population, predominantly wealthy mixed-blood Choctaws, owned some slaves. Therefore, the Choctaws entered into formal, diplomatic relations with the Confederacy, at which point the United States considered them in rebellion.

The Choctaw nation was little touched by the war. Two minor engagements were fought within the nation, but it was never occupied by troops. Very few Choctaws participated in the war on either side. The nation was overrun by refugees from the Creek and Cherokee nations, however, which were occupied by troops. As a result, they all suffered severe food shortages.

In their last treaty with the United States in 1866, the Choctaws were forced to sell their western lands as punishment for having sided with the Confederacy. The Choctaws also adopted a new constitution, which they patterned explicitly after the American form of government. It provided for a bi-cameral legislature, an executive branch, and a judicial branch.

The most profound effect of the treaty of 1866 was its granting of a railroad right of way, which had the same effect on the Choctaw nation in the last half of the nineteenth century as granting a right of way for a wagon road had in the early part of the century: Americans flooded into the country. By 1890, the Choctaws were outnumbered by Americans within their own country by more than three to one. The Americans did not have the right to own land, were not allowed representation within the nation, and were not allowed to send their children to the Choctaw public schools. They were required to pay taxes, which the Americans considered intolerable. Rather than leave, they clamored for Congress to abolish the Indian nations.

The U.S. Congress had already decided, unilaterally, that the government no longer needed to enter into treaties with Indian nations and that the Congress would legislate Indian affairs. In 1893, Congress authorized the president to seek the dissolution of the nations of the Five Civilized Tribes by persuading them to either allot their land to their individual citizens or cede it to the United States. Under the auspices of the so-called Dawes Commission that resulted, the government spent three years attempting to pressure the Indians into agreeing to allot their lands. Finally, under the threat that Congress would allot the lands for them, the Choctaws negotiated and signed the Atoka Agreement of 1897, providing for the allotment of the tribal estate. In this way they avoided being subjected to the much harsher terms they were being threatened with if they did not negotiate. In 1906, enrollment of tribal members for allotment was closed by the Congress, and in 1907, the Choctaw nation was absorbed into the new state of Oklahoma.

MODERN ERA

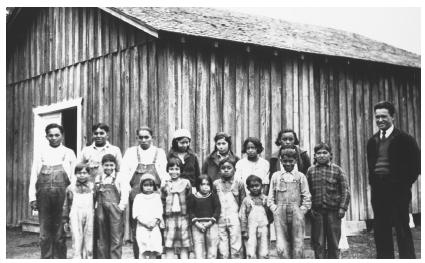

The U.S. government virtually ignored the Choctaws, who had remained in Mississippi until after the turn of the century. Then, in 1908 and 1916, the U.S. Congress commissioned studies on the people's condition. Although these Choctaws had remained isolated—living on the margins of the dominant society for generations—they retained their language and culture.

In 1918, the Bureau of Indian Affairs established the Choctaw Indian Agency in Philadelphia, Mississippi, with an initial budget of $75,000. The agency established schools in Choctaw communities and, in 1920, began purchasing land, which totaled 16,000 acres by 1944.

For the Choctaws in Oklahoma, allotment proved to be disastrous. Within a generation, most of the allotted land passed from Choctaw ownership to white ownership, often by fraudulent means. Enrolled Choctaws did not receive payment for the sale of the nation's public land until 1920, and for the sale of mineral resources until 1949. The President of the United States appointed a chief for the Choctaws until 1948, to administer these last remaining matters of tribal affairs.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Throughout the twentieth century, Indians have been both overwhelmed and ignored in Oklahoma. In the 1930s, Angie Debo completed the manuscript of her book And Still the Waters Run, which details the fraudulent acquisition of Indian land by people then prominent in Oklahoma politics. Debo reported that the dispossession of Indian land allotments was often achieved under the guise of guardianship. Although the University of Oklahoma Press refused to publish the work, it was finally published in 1940 by Princeton University Press. Shortly before her death, Debo read from the University of Oklahoma Press a rejection letter for a documentary film, quoting a characterization of one of her chapters as "dangerous." In fact, the fraud Debo reported was so widespread and perpetuated so openly, that hearing such cases made the Eastern District federal court of Oklahoma the second busiest federal district court in the United States.

Oklahoma has attempted to project the self-image of a state infused with a "pioneer spirit" that sets it apart from other places. Whether in Oklahoma or Hollywood, Americans usually refer to Indians in the past tense and as being apart from contemporary American culture. For most of the twentieth century, the media in Oklahoma has ignored Indians altogether, with the exception of an occasional piece deploring high rates of alcoholism among Indians or focusing on Indian dances as a means of attracting tourist dollars to the state.

The changes in media focus that have begun are in large part due to recent court rulings that allow Indian nations to operate gambling facilities on tribal land within Oklahoma: the mass media could not ignore the state's vigorous opposition to these rulings. Ironically, such attention has contributed to Oklahomans' slowly growing awareness that Indian nations are still intact and maintain their rights as sovereign nations.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

Observers have characterized the Choctaw attitude toward life as one that illustrates their belief that they do not exist for the benefit of any political, economic, military, or religious organization. Choctaws also did not favor spectacular ceremonies, religious or otherwise, showing a nearly complete lack of public display, except in the area of oratory.

Choctaws relished and excelled in public oratory, causing some observers to draw comparisons between the Choctaw communities and the small republics of Greek antiquity. When an occasion for public debate presented itself, a large brush arbor was constructed with a hole in the center of the roof. Whoever wanted to speak stood beneath the hole in the full heat of the Mississippi sun while the audience remained comfortably seated in the shade. The Choctaws said they could bear to listen as long as the speaker could bear to stand in the heat and speak.

Oratory skill provided an avenue to upward mobility in Choctaw society. Each district chief appointed a tichou mingo as the official spokesperson. The tichou mingo had a more visible presence in official life than did the chief. Aiahockatubbee, spokesman for the Okla Falaya district chief Moshulatubbee, is recognized as one of the greatest orators in Choctaw history. It is said that in the 1820s, when Christian missionaries had only been among the Choctaws for a few years, Aiahockatubbee gave them eloquent enunciations of traditional Choctaw beliefs, much to their consternation, although Choctaws gathered from far and wide to hear him. His presence is largely credited with enabling the missionaries to make headway among the Okla Falaya, where district chief Puckshenubbee was an early convert.

Choctaw chiefs were also skilled orators. Okla Hannali war chief Pushmataha was the most persuasive Choctaw public speaker of his generation, with only Aiahockatubbee as his peer. In open debate, Pushmataha persuaded the Choctaws not to join Tecumseh when Tecumseh visited their country seeking their enlistment in his pan-Indian alliance in 1811. The debate was witnessed and later recalled by John Pitchlynn, United States interpreter to the Choctaws.

A brief speech by Homassatubbee, district chief of the Okla Tanap, was recorded by the Americans at the negotiations for the Treaty of Fort Adams in 1801: "I understand our great father, General Washington, is dead, and that there is another beloved man appointed in his place, and that he is a well wisher of us. Our old brothers, the Chickasaws, have granted a road from Cumberland as far south as our boundary. I grant a continuance of that road which may be straightened. But the old path is not to be thrown away entirely, and a new one made. We are informed by these three beloved men that our father, the President, has sent us a yearly present of which we know nothing. Another thing our father, the President, has promised, without our asking, is that he would send women among us to teach our women to spin and weave. These women may first go among our half-breeds. We wish the old boundary which separates us and the whites to be marked over. We came here sober, to do business, and wish to return sober and request therefore that the liquor we are informed our friends have provided for us may remain in the store."

In traditional Choctaw society, serious personal disputes were resolved by an institution called a Choctaw duel. In such a duel, the disputants faced one another while their assistants, usually a brother or close friend appointed for the occasion, split their heads open with an ax. Both died, the dispute was resolved, and the community was spared the incessant bickering of people who could not get along with one another. One could not decline the challenge to a Choctaw duel without suffering everlasting disgrace within the community. Needless to say, Choctaws became adept at getting along with one another.

Observers of Choctaw habits consider ball play the most important social event in the life of the Choctaws. Called Ishtaboli, the game has been described in greatest detail by H. B. Cushman, the son of Choctaw missionaries who grew up among the Choctaws in the 1820s. Men and women had teams, and when two villages met on the field of play, every item of any value in the villages was riding on the outcome.

The object of the game was to sling a ball made of sewn skins from the webbed pocket at the end of a kapucha stick—a slender, stout stick made of hickory—and propel it so that it struck an upright plank at the end of the playing field, which was often a mile long or longer. There were dozens of players on each side, and there appeared to be no rules. Whatever means one might employ to stop the progress of the opponent toward the goal, including tackling, was allowed. Although Choctaws preferred that each player use two sticks to play the game, the Sioux used only one. The games demonstrated great skill at handling, throwing, and passing a ball, but the rough game often resulted in serious injury or death, for which there was no punishment. Today a version of Ishtaboli, called stickball, is still played by the Choctaws.

Language

Linguists classify the Choctaw language as Muskogean. It is closely related to the Creek language of the same classification. The Muskogean languages belong to the great Algonkian language family. Of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes (Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, Seminoles, and Cherokees), only the Cherokee, whose language is classified as Iroquoian, speak a non-Muskogean language. Unlike the other tribes, the Cherokees migrated to the southeast from the north, and over time their culture became similar to that of the southern neighbors with whom they have come to be identified among the Five Civilized Tribes.

Linguists theorize that many of the native peoples of the Southeast who had separate identities had at some time in the past been Choctaws. For example, the language of the Alabamas of the Muskogee Confederation (Creeks) is still identifiably Choctaw, although it is a distinctive dialect. The same is true of a number of smaller groups who lived in the region, many of whom did not survive contact with Europeans and the endemic diseases that accompanied European colonization. It appears that groups of people began leaving the Choctaw and establishing separate residences and separate identities many years ago, a process that has continued into recent times. The Chickasaw language is still so similar to Choctaw, for instance, that linguists surmise that the separation of the two could not have occurred very long ago.

Language is also a key to gaining some understanding of how influential the Choctaws were among the native people of North America at the time of early European contact. Ancient trading paths radiated throughout the continent, facilitating commercial intercourse between greatly distant peoples. A pidgin version of the Choctaw language was used along many of the trading paths as the universal medium of trade communication among a wide assortment of diverse peoples. The trading paths were spread over a vast region that encompassed most of what is now generally referred to as the South and extended to other areas.

The missionaries used the Okla Falaya dialect of the Choctaw language to translate ancient myths of the Hebrews for hymns and other proselytizing materials, which in time made the Okla Falaya dialect the standard dialect of the Choctaw language among the Choctaws who were removed to

Family and Community Dynamics

Europeans and Americans universally failed to appreciate or report the powerful and predominant role of women in Choctaw traditional life. Choctaw culture is matrilineal and, in many respects, matriarchal. Choctaw males were conspicuous in their roles as warriors, and war chiefs exercised a good deal of authority in time of war and conducted the diplomatic business of the nation. Likening such practices to those of their own patriarchal models, European observers failed to appreciate that the real decision-making power in times of peace was found among the women within the nation. Modern Choctaws have adjusted to the expectations of their colonizers regarding gender roles in visible positions of leadership, but in Choctaw family and social life, and in many organizations, a mature female is found at the very center of the life of the group, whether visible to outsiders or not.

Geographic divisions among ancient Choctaw tribes were roughly decided according to the crests of watersheds. In present-day east-central Mississippi, the headwaters of three rivers can be found: the Pearl, which drains toward the southwest before turning south to empty into the Gulf of Mexico near Lake Pontchartrain, where the Pearl forms the border with Louisiana; the Chickasawhay, an upper tributary of the Pascagoula, which flows toward the south into the Gulf of Mexico near the Alabama border; and the Noxubee, an upper tributary of the Tombigbee, which flows southeast before turning south to flow into Mobile Bay.

The villages of the Okla Falaya (Long People) lived along the headwaters of the Pearl on the western side of the nation. On the eastern side of the nation, along the headwaters of the Noxubee, lived the Okla Tanap (People of the Opposite Side). And the villages of the Okla Hannali (The Six Town People) were along the headwaters of the Chickasawhay at the southern side of the nation.

The Okla Falaya's relations with the Chickasaws, their nearest northern neighbors, were more congenial than those of other Choctaw divisions. Likewise, the Okla Tanap were generally on good terms with their eastern neighbors, the Choctaw-speaking Alabamas of the Muskogee Confederation, and the Okla Hannali enjoyed frequent contact with the Indians around Mobile Bay. In addition, the Choctaws had chiefs within their nation who served as spokesmen and apologists to neighboring tribes. Called fanni mingoes, or squirrel chiefs, they provided individual Choctaws with an opportunity to seek redress for some grievance or an injury caused by an outsider from the fanni mingo, rather than seek revenge against the offending tribe. The fanni mingo held counsel with the tribe whose interests he represented and tried to resolve the matter to the satisfaction of all parties.

Choctaw towns were divided into peace towns and war towns—called white towns and red towns—and chiefs were either peace chiefs or war chiefs. Neither Europeans nor Americans became well enough acquainted with the inner workings of Choctaw society to accurately describe the duties of the various participants in Choctaw public life. Most observers made assumptions based on models from European government, which were frequently at great variance with Choctaw practice.

Tribal divisions of the Choctaw nation operated with virtual independence. The republic was, in fact, a loose confederation. Within tribal divisions, villages also exercised a great deal of local autonomy. And individual Choctaws exercised such a large degree of personal freedom that the system bordered on anarchy. It was able to function successfully only because Choctaws exercised remarkable restraint regarding encroachment upon the rights of others within the group.

CELEBRATIONS AND FESTIVALS

The premiere annual event of the Mississippi Choctaws is the Choctaw Indian Fair, a four-day event in July. Established in 1949, the fair draws more than 20,000 visitors each year and features the Stickball World Championship, national entertainers, and traditional Choctaw costumes and food (Choctaw Indian Fair, Choctaw Reservation, P.O. Box 6010, Philadelphia, Mississippi 39350).

The largest annual celebration in the Oklahoma nation is the four-day Labor Day Celebration at Tuskahoma, which dates from the early 1900s and now draws thousands of Choctaws each year. It includes a viewing of the tribal buffalo herd; softball, horseshoe, volleyball and checkers tournaments; national entertainers; a mid-way carnival and exhibition halls featuring dozens of crafts booths; all-night gospel singing on Sunday night; and a parade, a State of the Nation address by the Principal Chief, and a free barbecue dinner on Monday.

Employment and Economic Traditions

The Mississippi Choctaws have lured industry to the reservation in recent years. With the construction of an industrial park in 1973, at the Pearl River community, a division of General Motors Corporation established the Chata Wire Harness Enterprise, which assembles electrical components for automobiles. Shortly thereafter, the American Greeting Corporation's Choctaw Greeting Enterprise began production, and the Oxford Investment Company started manufacturing automobile radio speakers at the Choctaw Electronics Enterprise. These companies and others currently employ more than 1,000 Choctaws on the reservation.

Recent decades have also brought a construction boom to the reservation of the Mississippi Choctaws. In 1965, the Choctaw Housing Authority constructed the first of more than 200 modern homes on the reservation. In 1969, the Chata Development company, which builds and remodels homes, and constructs offices and buildings for the nation, was established. The Choctaw Health Center, a 43-bed hospital, opened in 1976.

The Oklahoma Choctaws have built community centers and clinics in towns throughout the nation. The Choctaw Housing Authority has provided thousands of Choctaws with low-cost modern homes. The nation operates the historic Indian Hospital at Talihina, which it acquired from the Indian Health Service; it purchased the sprawling Arrowhead Resort on Lake Eufaula from the state of Oklahoma and operates it as a tourist and convention facility. Tribal industries include the Choctaw Finishing Plant and the Choctaw Village Shopping Center in Idabel, and the Choctaw Travel Plaza in Durant.

The buildings and grounds at the historic Choctaw Council House at Tushkahoma, in the center of the nation, have been restored, and the stately three-story brick Council House has been converted into a museum and gift shop. The Choctaw Tribal Council holds its monthly meetings in the new, modern

By far the greatest economic gain in the nation has been through the inauguration of high stakes Indian bingo. Charter buses bring bingo players daily from as far away as Dallas, Texas, to the huge Choctaw Bingo Palace in Durantto.

Politics and Government

In 1945, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior granted the Choctaws formal federal recognition, approving a constitution and bylaws for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. The constitution provided for the election of a tribal council, which then appointed a tribal chairman. The land that had been acquired for them became a reservation.

The reservation remains outside of the political and judicial jurisdiction of the state of Mississippi. A 1974 revision of the Choctaw Nation's Constitution provides for the popular election of the chief to a four-year term. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, allowed the Choctaws in Oklahoma to elect an advisory council, and in 1948, they were allowed to elect their own principal chief. Impetus toward reorganizing the nation met another shift in federal policy in 1953, when the U.S. Congress enacted House Concurrent Resolution 108, under which the federal government sought to terminate its relationship with all Indian nations in the United States. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 finally allowed the Choctaws a measure of self-government within the state of Oklahoma.

In 1976, the Choctaws purchased the campus of the former Presbyterian College in Durant, Oklahoma, as their national capitol and in 1978 adopted a new constitution—their first since the constitution of 1866 had been abrogated in 1906. Designating themselves The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, they adopted a tribal council form of government led by a principal chief elected by popular vote of the entire nation and council members elected by popular vote of council districts.

Since the mid-1970s, the tribal estate has steadily increased, along with the nation's administrative activities, enabling the Oklahoma Choctaw to exercise more vestiges of sovereignty. A recent federal court ruling stated that the state of Oklahoma could no longer exercise police powers on Indian land within the state. As a result the Choctaw Nation Police were organized. The Choctaw nation and the state of Oklahoma signed a pact to cross-deputize all law enforcement officers of both governments for the welfare and protection of all citizens.

Individual and Group Contributions

ACADEMIA

Anna Lewis was an historian, whose doctoral dissertation, Along The Arkansas, is a study of French-Indian relations on the lower Arkansas River frontier in the eighteenth century; in 1930, Lewis became the first woman to receive a Ph.D. from the University of Oklahoma; she pursued a distinguished teaching career at the Oklahoma College for Women, now the University of Science and Arts, in Chickasaha, Oklahoma, while devoting her life to researching a biography of Pushmataha (a war chief of the Okla Hannali Choctaw tribal division and the most influential Choctaw leader of the early nineteenth century), Chief Pushmataha, American Patriot, published in 1959. Clara Sue Kidwell, formerly a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, now works for the Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution; she coauthored the invaluable study The Choctaws: A Critical Bibliography in 1980. Muriell Wright was the granddaughter of Allen Wright, Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation in the nineteenth century; for two decades, she served as editor of The Chronicles of Oklahoma, the quarterly historical scholarly journal of the Oklahoma Historical Society; in 1959, she produced A Guide to the Indian tribes of Oklahoma, which provides a summary of the history, culture, and contemporary status of the 65 Indian nations that were either original residents of, or were removed to the area before statehood.

ART

Linda Lomahaftewa (1947– ) is an accomplished Hopi/Choctaw artist and art instructor. Her work, which reflects the spirituality and storytelling traditions of her background, has garnered numerous awards and exhibitions. Film producer, director, and writer Phil Lucas (1942– ) creates realistic images of his people in an effort to combat the stereotypes.

LITERATURE

M. Cochise Anderson is a poet whose work has appeared in World of Poetry Anthology (1983) and in Nitassinan Notre Terre (1990). Jim Barnes is a poet and editor of Chariton Review at Northwest Missouri State University, Kirksville, Missouri; Barnes won the Oklahoma Book Award for his The Sawdust War (1993), a volume of poetry. He was awarded a Ful-bright fellowship to the University of Lausanne in Switzerland (1993-1994); among Barnes' other verse collections are American Book of the Dead (1982), A Season of Loss (1985), La Plata Cantata (1989), The Fish on Poteau Mountain (1980), and This Crazy Land (1980). Roxy Gordon has published more than 200 poems, articles, and short fiction in Rolling Stone, Village Voice, Texas Observer, Greenfield Review, Dallas Times Herald and Dallas Morning News ; his fiction has appeared in anthologies including Earth Power Coming, edited by Simon J. Ortiz in 1983; Gordon's poetry is collected in Unfinished Business, West Texas Midcentury, and Small Circles. Beatrice Harrell has contributed memoirs of her mother's experiences in the Choctaw boarding schools in such publications as The Four Directions: American Indian Literary Quarterly. The Choctaw Story of How Thunder and Lightning Came to Be is one of several books in which Harrell recounts traditional Choctaw stories. LeAnn Howe is a widely published poet, essayist, short story writer, and playwright; her poetry has appeared in anthologies such as Gatherings IV: The En'owkin Journal of First North American People and Studies in American Indian Literatures; her short stories have appeared in many collections, including A Stand Up Reader (1987), Coyote Papers (1987), and the anthology Earth Song, Sky Spirit: Short Stories of the Contemporary Native American Experience (1993); Howe is perhaps best known for her saucy essay, "An American in New York," in Spider-woman's Granddaughters, edited by Paula Gunn Allen and published in 1989; a recent radio broadcast of her play Indian Radio Days (co-authored with Roxy Gordon) was transmitted by satellite to stations as far away as Alaska. Gary McLain's nonfiction works include Keepers of the Fire (1987), Indian America (1990), and The Indian Way (1991). Louis Owens is a novelist and co-editor of the American Indian Literature Series of the University of Oklahoma Press; currently an English professor at the University of New Mexico, Owens formerly taught at the University of California at Santa Cruz; his novels include Wolfsong (1991), The Sharpest Sight (1992), and Bone Game (1994); Owens' Other Destines: Understanding The American Indian Novel (1992) is a critical study. Ronald Burns Querry, a descendant of Okla Hannali Choctaws, was an English professor at the University of Oklahoma and was former editor of horse industry magazines; a professional farrier (horseshoer); and the author of The Death of Bernadette Lefthand (1993), which received both the Border Regional Library Association Regional Book Award and the Mountains and Plains Booksellers Association Award as one of the best novels published in 1993; Querry is also the editor of Growing Old at Willie Nelson's Picnic, and Other Sketches of Life in the Southwest (1983), and author of his "unauthorized" biography, I See By My Get-Up (1987). In 1992, Wallace Hampton Tucker became the first three-time winner of the Best Play Prize of the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muscogee, Oklahoma, for his play Fire On Bending Mountain; Tucker also won the first two prizes awarded by the biennial competition in 1974 and in 1976.

JOURNALISM

Judy Allen is a long-time editor of Bishinik, the official monthly publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, which is mailed to every registered voter of the nation. Len Green, the late newspaperman, was the first editor of Bishinik, where he set a high standard for others to follow; Green was also managing editor of the McCurtain Gazette, in Idabel, Oklahoma, for 30 years; early issues of Bishinik contain his scholarly writings about Choctaw history and treaties; for the bicentennial celebration, Green published 200 Years Ago In The Red River Valley (1976), a study of Choctaw country in the West two generations before the Choctaws moved there. Scott Kayla Morrison collaborated with LeAnn Howe on the investigative article "Sewage of Foreigners" ( Federal Bar Journal & Notes, July, 1992), a detailed exposé that focused on contract negotiations by the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians to allow for toxic waste dumps on Choctaw lands in Mississippi. Morrison has worked as a legal services attorney among the Choctaws in Mississippi and as director of the Native American Office of Jobs in the Environment; in the summer of 1993, Oklahoma Today named her in its "Who's Who in Indian Country" in recognition of her environmental work; her short stories and essays have appeared in publications including The Four Directions: American Indian Literary Quarterly and Turtle Quarterly (Native American Center for the Living Arts, Niagara Falls, New York), and in the anthology The Colour of Resistance (1994).

Media

Bishinik.

Official monthly publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Contact: Judy Allen, Director.

Address: P.O. Drawer 1210, Durant, Oklahoma 74701.

Telephone: (580) 924-8280.

Fax: (580)924-4148.

E-mail: bishinik@choctawnation.com.

Choctaw Community News.

Official monthly publication of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

Contact: Julie Kelsey, Editor.

Address: Communications Program, P.O. Box 6010, Philadelphia, Mississippi 39350.

Telephone: (601) 656-1992.

Organizations and Associations

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Contact: Chief Gregory E. Pyle.

Address: P.O. Drawer 1210, Durant, Oklahoma 74702-1210.

Telephone: (800) 522-6170; or (580) 924-8280.

Fax: (580) 924-4148.

E-mail: chief@choctawnation.com.

Online: http://www.choctawnation.com .

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

Address: Highway 16 West, P.O. Box 6010, Philadelphia, Mississippi 39360.

Telephone: (601) 650-1537.

Fax: (601) 650-3684.

Sources for Additional Study

After Removal: The Choctaw in Mississippi, edited by Samuel J. Wells and Roseanna Tubby. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1986.

Choctaw & Chickasaw Early Census Records, compiled by Betty Couch Wiltshire. Carrollton, Mississippi: Pioneer Publishing Company, 1997.

The Choctaw Before Removal, edited by Carolyn Keller Reeves. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1985.

Debo, Angie. "Indians, Outlaws, and Angie Debo," The American Experience, PBS Video, 1988.

——. The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic, second edition. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

DeRosier, Arthur H., Jr. The Removal of the Choctaw Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1970.

Foreman, Grant. The Five Civilized Tribes. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1934.

Howard, James H., and Victoria L Levine. Choctaw Music & Dance. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Jordan, H. Glenn. "Choctaw Colonization in Oklahoma," in America's Exiles: Indian Colonization in Oklahoma, edited by Arrell Morgan Gibson, 1976.

Kidwell, Clara Sue, and Charles Roberts. The Choctaws: A Critical Bibliography. Bloomington: Indiana University Press for the Newberry Library, 1980.

McKee, Jesse O. The Choctaw. New York: Chelsea House, 1989.

McKee, Jesse O., and Jon A. Schlenker. The Choctaws: Cultural Evolution of a Native American Tribe. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1980.