Puerto rican americans

by Derek Green

Overview

The island of Puerto Rico (formerly Porto Rico) is the most easterly of the Greater Antilles group of the West Indies island chain. Located more than a thousand miles southeast of Miami, Puerto Rico is bounded on the north by the Atlantic Ocean, on the east by the Virgin Passage (which separates it from the Virgin Islands), on the south by the Caribbean Sea, and on the west by the Mona Passage (which separates it from the Dominican Republic). Puerto Rico is 35 miles wide (from north to south), 95 miles long (from east to west) and has 311 miles of coastline. Its land mass measures 3,423 square miles—about two-thirds the area of the state of Connecticut. Although it is considered to be part of the Torrid Zone, the climate of Puerto Rico is more temperate than tropical. The average January temperature on the island is 73 degrees, while the average July temperature is 79 degrees. The record high and low temperatures recorded in San Juan, Puerto Rico's northeastern capital city, are 94 degrees and 64 degrees, respectively.

According to the 1990 U.S. Census Bureau report, the island of Puerto Rico has a population of 3,522,037. This represents a three-fold increase since 1899—and 810,000 of those new births occurred between the years of 1970 and 1990 alone. Most Puerto Ricans are of Spanish ancestry. Approximately 70 percent of the population is white and about 30 percent is of African or mixed descent. As in many Latin American cultures, Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion, but Protestant faiths of various denominations have some Puerto Rican adherents as well.

Puerto Rico is unique in that it is an autonomous Commonwealth of the United States, and its people think of the island as un estado libre asociado, or a "free associate state" of the United States—a closer relationship than the territorial possessions of Guam and the Virgin Islands have to America. Puerto Ricans have their own constitution and elect their own bicameral legislature and governor but are subject to U.S executive authority. The island is represented in the U.S House of Representatives by a resident commissioner, which for many years was a nonvoting position. After the 1992 U.S. presidential election, however, the Puerto Rican delegate was granted the right to vote on the House floor. Because of the Puerto Rico's commonwealth status, Puerto Ricans are born as natural American citizens. Therefore all Puerto Ricans, whether born on the island or the mainland, are Puerto Rican Americans.

Puerto Rico's status as a semiautonomous Commonwealth of the United States has sparked considerable political debate. Historically, the main conflict has been between the nationalists, who support full Puerto Rican independence, and the statists, who advocate U.S. statehood for Puerto Rico. In November of 1992 an island-wide referendum was held on the issue of statehood versus continued Commonwealth status. In a narrow vote of 48 percent to 46 percent, Puerto Ricans opted to remain a Commonwealth.

HISTORY

Fifteenth-century Italian explorer and navigator Christopher Columbus, known in Spanish as Cristobál Colón, "discovered" Puerto Rico for Spain on November 19, 1493. The island was conquered for Spain in 1509 by Spanish nobleman Juan Ponce de León (1460-1521), who became Puerto Rico's first colonial governor. The name Puerto Rico, meaning "rich port," was given to the island by its Spanish conquistadors (or conquerors); according to tradition, the name comes from Ponce de León himself, who upon first seeing the port of San Juan is said to have exclaimed, "¡Ay que puerto rico!" ("What a rich port!").

Puerto Rico's indigenous name is Borinquen ("bo REEN ken"), a name given by its original inhabitants, members of a native Caribbean and South American people called the Arawaks. A peaceful agricultural people, the Arawaks on the island of Puerto Rico were enslaved and virtually exterminated at the hands of their Spanish colonizers. Although Spanish heritage has been a matter of pride among islander and mainlander Puerto Ricans for hundreds of years—Columbus Day is a traditional Puerto Rican holiday—recent historical revisions have placed the conquistadors in a darker light. Like many Latin American cultures, Puerto Ricans, especially younger generations living in the mainland United States, have become increasingly interested in their indigenous as well as their European ancestry. In fact, many Puerto Ricans prefer to use the terms Boricua ("bo REE qua") or Borrinqueño ("bo reen KEN yo") when referring to each other.

Because of its location, Puerto Rico was a popular target of pirates and privateers during its early colonial period. For protection, the Spanish constructed forts along the shoreline, one of which, El Morro in Old San Juan, still survives. These fortifications also proved effective in repelling the attacks of other European imperial powers, including a 1595 assault from British general Sir Francis Drake. In the mid-1700s, African slaves were brought to Puerto Rico by the Spanish in great numbers. Slaves and native Puerto Ricans mounted rebellions against Spain throughout the early and mid-1800s. The Spanish were successful, however, in resisting these rebellions.

In 1873 Spain abolished slavery on the island of Puerto Rico, freeing black African slaves once and for all. By that time, West African cultural traditions had been deeply intertwined with those of the native Puerto Ricans and the Spanish conquerors. Intermarriage had become a common practice among the three ethnic groups.

MODERN ERA

As a result of the Spanish-American War of 1898, Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris on December 19, 1898. In 1900 the U.S. Congress established a civil government on the island. Seventeen years later, in response to the pressure of Puerto Rican activists, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones Act, which granted American citizenship to all Puerto Ricans. Following this action, the U.S. government instituted measures to resolve the various economic and social problems of the island, which even then was suffering from overpopulation. Those measures included the introduction of American currency, health programs, hydroelectric power and irrigation programs, and economic policies designed to attract U.S. industry and provide more employment opportunities for native Puerto Ricans.

In the years following World War II, Puerto Rico became a critical strategic location for the U.S. military. Naval bases were built in San Juan Harbor and on the nearby island of Culebra. In 1948 Puerto Ricans elected Luis Muñoz Marín governor of the island, the first native puertorriqueño to hold such a post. Marín favored Commonwealth status for Puerto Rico. The question of whether to continue the Commonwealth relationship with the United States, to push for U.S. statehood, or to rally for total independence has dominated Puerto Rican politics throughout the twentieth century.

Following the 1948 election of Governor Muñoz, there was an uprising of the Nationalist Party, or independetistas, whose official party platform included agitation for independence. On November 1, 1950, as part of the uprising, two Puerto Rican nationalists carried out an armed attack on Blair House, which was being used as a temporary residence by U.S. President Harry Truman. Although the president was unharmed in the melee, one of the assailants and one Secret Service presidential guard were killed by gunfire.

After the 1959 Communist revolution in Cuba, Puerto Rican nationalism lost much of its steam; the main political question facing Puerto Ricans in the mid-1990s was whether to seek full statehood or remain a Commonwealth.

EARLY MAINLANDER PUERTO RICANS

Since Puerto Ricans are American citizens, they are considered U.S. migrants as opposed to foreign immigrants. Early Puerto Rican residents on the mainland included Eugenio María de Hostos (b. 1839), a journalist, philosopher, and freedom fighter who arrived in New York in 1874 after being exiled from Spain (where he had studied law) because of his outspoken views on Puerto Rican independence. Among other pro-Puerto Rican activities, María de Hostos founded the League of Patriots to help set up the Puerto Rican civil government in 1900. He was aided by Julio J. Henna, a Puerto Rican physician and expatriate. Nineteenth-century Puerto Rican statesman Luis Muñoz Rivera—the father of Governor Luis Muñoz Marín—lived in Washington D.C., and served as Puerto Rico's ambassador to the States.

SIGNIFICANT IMMIGRATION WAVES

Although Puerto Ricans began migrating to the United States almost immediately after the island became a U.S. protectorate, the scope of early migration was limited because of the severe poverty of average Puerto Ricans. As conditions on the island improved and the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States grew closer, the number of Puerto Ricans who moved to the U.S. mainland increased. Still, by 1920, less than 5,000 Puerto Ricans were living in New York City. During World War I, as many as 1,000 Puerto Ricans—all newly naturalized American citizens—served in the U.S. Army. By World War II that number soared to over 100,000 soldiers. The hundred-fold increase reflected the deepening cooperation between Puerto Rico and the mainland States. World War II set the stage for the first major migration wave of Puerto Ricans to the mainland.

That wave, which spanned the decade between 1947 and 1957, was brought on largely by economic factors: Puerto Rico's population had risen to nearly two million people by mid-century, but the standard of living had not followed suit. Unemployment was high on the island while opportunity was dwindling. On the mainland, however, jobs were widely available. According to Ronald Larsen, author of The Puerto Ricans in America, many of those jobs were in New York City's garment district. Hard-working Puerto Rican women were especially welcomed in the garment district shops. The city also provided the sort of low-skilled service industry jobs that non-English speakers needed to make a living on the mainland.

New York City became a major focal point for Puerto Rican migration. Between 1951 and 1957 the average annual migration from Puerto Rico to New York was over 48,000. Many settled in East Harlem, located in upper Manhattan between 116th and 145th streets, east of Central Park. Because of its high Latino population, the district soon came to be known as Spanish Harlem. Among New York City puertorriqueños, the Latino-populated area was referred to as el barrio, or "the neighborhood." Most first-generation migrants to the area were young men who later sent for their wives and children when finances allowed.

By the early 1960s the Puerto Rican migration rate slowed down, and a "revolving door" migratory pattern—a back-and-forth flow of people between the island and the mainland—developed. Since then, there have been occasional bursts of increased migration from the island, especially during the recessions of the late 1970s. In the late 1980s Puerto Rico became increasingly plagued by a number of social problems, including rising violent crime (especially drug-associated crime), increased overcrowding, and worsening unemployment. These conditions kept the flow of migration into the United States steady, even among professional classes, and caused many Puerto Ricans to remain on the mainland permanently. According to U.S. Census Bureau statistics, more than 2.7 million Puerto Ricans were living in the mainland Unites States by 1990, making Puerto Ricans the second-largest Latino group in the nation, behind Mexican Americans, who number nearly 13.5 million.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Most early Puerto Rican migrants settled in New York City and, to a lesser degree, in other urban areas in the northeastern United States. This migration pattern was influenced by the wide availability of industrial and service-industry jobs in the eastern cities. New York remains the chief residence of Puerto Ricans living outside of the island: of the 2.7 million Puerto Ricans living on the mainland, over 900,000 reside in New York City, while another 200,000 live elsewhere in the state of New York.

That pattern has been changing since the 1990s, however. A new group of Puerto Ricans— most of them younger, wealthier, and more highly educated than the urban settlers—have increasingly begun migrating to other states, especially in the South and Midwest. In 1990 the Puerto Rican population of Chicago, for instance, was over 125,000. Cities in Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Massachusetts also have a significant number of Puerto Rican residents.

Acculturation and Assimilation

The history of Puerto Rican American assimilation has been one of great success mixed with serious problems. Many Puerto Rican mainlanders hold high-paying white collar jobs. Outside of New York City, Puerto Ricans often boast higher college graduation rates and higher per capita incomes than their counterparts in other Latino groups, even when those groups represent a much higher proportion of the local population.

However, U.S. Census Bureau reports indicate that for at least 25 percent of all Puerto Ricans living on the mainland (and 55 percent living on the island) poverty is a serious problem. Despite the presumed advantages of American citizenship, Puerto Ricans are—overall—the most economically disadvantaged Latino group in the United States. Puerto Rican communities in urban areas are plagued by problems such as crime, drug-use, poor educational opportunity, unemployment, and the breakdown of the traditionally strong Puerto Rican family structure. Since a great many Puerto Ricans are of mixed Spanish and African descent, they have had to endure the same sort of racial discrimination often experienced by African Americans. And some Puerto Ricans are further handicapped by the Spanish-to-English language barrier in American cities.

Despite these problems, Puerto Ricans, like other Latino groups, are beginning to exert more political power and cultural influence on the mainstream population. This is especially true in cities like New York, where the significant Puerto Rican population can represent a major political force when properly organized. In many recent elections Puerto Ricans have found themselves in the position of holding an all-important "swingvote"—often occupying the sociopolitical ground between African Americans and other minorities on the one hand and white Americans on the other. The pan-Latin sounds of Puerto Rican singers Ricky Martin, Jennifer Lopez, and Marc Anthony, and jazz musicians such as saxophonist David Sanchez, have not only brought a cultural rivival, they have increased interest in Latin music in the late 1990s. Their popularity has also had a legitimizing effect on Nuyorican, a term coined by Miguel Algarin, founder of the Nuyorican Poet's Café in New York, for the unique blend of Spanish and English used among young Puerto Ricans living in New York City.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

The traditions and beliefs of Puerto Rican islanders are heavily influenced by Puerto Rico's Afro-Spanish history. Many Puerto Rican customs and superstitions blend the Catholic religious traditions of Spaniards and the pagan religious beliefs of the West African slaves who were brought to the island beginning in the sixteenth century. Though most Puerto Ricans are strict Roman Catholics, local customs have given a Caribbean flavor to some standard Catholic ceremonies. Among these are weddings, baptisms and funerals. And like other Caribbean islanders and Latin Americans, Puerto Ricans traditionally believe in espiritismo, the notion that the world is populated by spirits who can communicate with the living through dreams.

In addition to the holy days observed by the Catholic church, Puerto Ricans celebrate several other days that hold particular significance for them as a people. For instance, El Dia de las Candelarias, or "candlemas," is observed annually on the evening of February 2; people build a massive bonfire around which they drink and dance and

Many Puerto Rican customs revolve around the ritual significance of food and drink. As in other Latino cultures, it is considered an insult to turn down a drink offered by a friend or stranger. It is also customary for Puerto Ricans to offer food to any guest, whether invited or not, who might enter the household: failure to do so is said to bring hunger upon one's own children. Puerto Ricans traditionally warn against eating in the presence of a pregnant woman without offering her food, for fear she might miscarry. Many Puerto Ricans also believe that marrying or starting a journey on a Tuesday is bad luck, and that dreams of water or tears are a sign of impending heartache or tragedy. Common centuries-old folk remedies include the avoidance of acidic food during menstruation and the consumption of asopao ("ah so POW"), or chicken stew, for minor ailments.

MISCONCEPTIONS AND STEREOTYPES

Although awareness of Puerto Rican culture has increased within mainstream America, many common misconceptions still exist. For instance, many other Americans fail to realize that Puerto Ricans are natural-born American citizens or wrongly view their native island as a primitive tropical land of grass huts and grass skirts. Puerto Rican culture is often confused with other Latino American cultures, especially that of Mexican Americans. And because Puerto Rico is an island, some mainlanders have trouble distinguishing Pacific islanders of Polynesian descent from the Puerto Rican people, who have Euro-African and Caribbean ancestry.

CUISINE

Puerto Rican cuisine is tasty and nutritious and consists mainly of seafood and tropical island vegetables, fruits, and meats. Although herbs and spices are used in great abundance, Puerto Rican cuisine is not spicy in the sense of peppery Mexican cuisine. Native dishes are often inexpensive, though they require some skill in preparation. Puerto Rican

Many Puerto Rican dishes are seasoned with a savory mixture of spices known as sofrito ("so-FREE-toe"). This is made by grinding fresh garlic, seasoned salt, green peppers, and onions in a pilón ("pee-LONE"), a wooden bowl similar to a mortar and pestle, and then sautéing the mixture in hot oil. This serves as the spice base for many soups and dishes. Meat is often marinated in a seasoning mixture known as adobo, which is made from lemon, garlic, pepper, salt, and other spices. Achiote seeds are sautéed as the base for an oily sauce used in many dishes.

Bacalodo ("bah-kah-LAH-doe"), a staple of the Puerto Rican diet, is a flaky, salt-marinated cod fish. It is often eaten boiled with vegetables and rice or on bread with olive oil for breakfast. Arroz con pollo, or rice and chicken, another staple dish, is served with abichuelas guisada ("ah-bee-CHWE-lahs gee-SAH-dah"), marinated beans, or a native Puerto Rican pea known as gandules ("gahn-DOO-lays"). Other popular Puerto Rican foods include asopao ("ah-soe-POW"), a rice and chicken stew; lechón asado ("le-CHONE ah-SAH-doe"), slow-roasted pig; pasteles ("pah-STAY-lehs"), meat and vegetable patties rolled in dough made from crushed plantains (bananas); empanadas dejueyes ("em-pah-NAH-dahs deh WHE-jays"), Puerto Rican crab cakes; rellenos ("reh-JEY-nohs"), meat and potato fritters; griffo ("GREE-foe"), chicken and potato stew; and tostones, battered and deep fried plantains, served with salt and lemon juice. These dishes are often washed down with cerveza rúbia ("ser-VEH-sa ROO-bee-ah"), "blond" or light-colored American lager beer, or ron ("RONE") the world-famous, dark-colored Puerto Rican rum.

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES

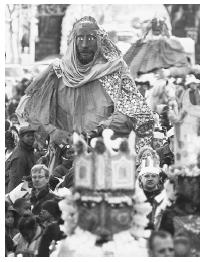

Traditional dress in Puerto Rico is similar to other Caribbean islanders. Men wear baggy pantalons (trousers) and a loose cotton shirt known as a guayaberra. For certain celebrations, women wear colorful dresses or trajes that have African influence. Straw hats or Panama hats ( sombreros de jipijipa ) are often worn on Sundays or holidays by men. Spanish-influenced garb is worn by musicians and dancers during performances—often on holidays.

The traditional image of the jíbaro, or peasant, has to some extent remained with Puerto Ricans. Often depicted as a wiry, swarthy man wearing a straw hat and holding a guitar in one hand and a machete (the long-bladed knife used for cutting sugarcane) in the other, the jíbaro to some symbolizes the island's culture and its people. To others, he is an object of derision, akin to the derogatory image of the American hillbilly.

DANCES AND SONGS

Puerto Rican people are famous for throwing big, elaborate parties—with music and dancing—to celebrate special events. Puerto Rican music is polyrhythmic, blending intricate and complex African percussion with melodic Spanish beats. The traditional Puerto Rican group is a trio, made up of a qauttro (an eight-stringed native Puerto Rican instrument similar to a mandolin); a guitarra, or guitar; and a basso, or bass. Larger bands have trumpets and strings as well as extensive percussion sections in which maracas, guiros, and bongos are primary instruments.

Although Puerto Rico has a rich folk music tradition, fast-tempoed salsa music is the most widely known indigenous Puerto Rican music. Also the name given to a two-step dance, salsa has gained popularity among non-Latin audiences. The merengue, another popular native Puerto Rican dance, is a fast step in which the dancers' hips are in close contact. Both salsa and merengue are favorites in American barrios. Bombas are native Puerto Rican songs sung a cappella to African drum rhythms.

HOLIDAYS

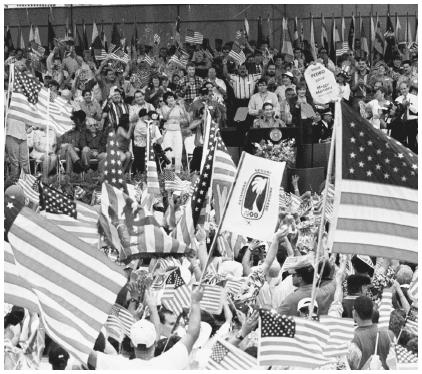

Puerto Ricans celebrate most Christian holidays, including La Navidád (Christmas) and Pasquas (Easter), as well as El Año Nuevo (New Year's Day). In addition, Puerto Ricans celebrate El Dia de Los Tres Reyes, or "Three King's Day," each January 6. It is on this day that Puerto Rican children expect gifts, which are said to be delivered by los tres reyes magos ("the three wise men"). On the days leading up to January 6, Puerto Ricans have continuous celebrations. Parrandiendo (stopping by) is a practice similar to American and English caroling, in which neighbors go visiting house to house. Other major celebration days are El Día de Las Raza (The Day of the Race—Columbus Day) and El Fiesta del Apostal Santiago (St. James Day). Every June, Puerto Ricans in New York and other large cities celebrate Puerto Rican Day. The parades held on this day have come to rival St. Patrick's Day parades and celebrations in popularity.

HEALTH ISSUES

There are no documented health problems or mental health problems specific to Puerto Ricans. However, because of the low economic status of many Puerto Ricans, especially in mainland inner-city settings, the incidence of poverty-related health problems is a very real concern. AIDS, alcohol and drug dependency, and a lack of adequate health care coverage are the biggest health-related concerns facing the Puerto Rican community.

Language

There is no such thing as a Puerto Rican language. Rather, Puerto Ricans speak proper Castillian Spanish, which is derived from ancient Latin. While Spanish uses the same Latin alphabet as English, the letters "k" and "w" occur only in foreign words. However, Spanish has three letters not found in English: "ch" ("chay"), "ll" ("EL-yay"), and "ñ" ("AYN-nyay"). Spanish uses word order, rather than noun and pronoun inflection, to encode meaning. In addition, the Spanish language tends to rely on diacritical markings such as the tilda (~) and the accento (') much more than English.

The main difference between the Spanish spoken in Spain and the Spanish spoken in Puerto Rico (and other Latin American locales) is pronunciation. Differences in pronunciation are similar to the regional variations between American English in the southern United States and New England. Many Puerto Ricans have a unique tendency among Latin Americans to drop the "s" sound in casual conversation. The word ustéd (the proper form of the pronoun "you"), for instance, may be pronounced as "oo TED" rather than "oo STED." Likewise, the participial suffix " -ado " is often changed by Puerto Ricans. The word cemado (meaning "burned") is thus pronounced "ke MOW" rather than "ke MA do."

Although English is taught to most elementary school children in Puerto Rican public schools, Spanish remains the primary language on the island of Puerto Rico. On the mainland, many first-generation Puerto Rican migrants are less than fluent in English. Subsequent generations are often fluently bilingual, speaking English outside of the home and Spanish in the home. Bilingualism is especially common among young, urbanized, professional Puerto Ricans.

Long exposure of Puerto Ricans to American society, culture, and language has also spawned a unique slang that has come to be known among many Puerto Ricans as "Spanglish." It is a dialect that does not yet have formal structrure but its use in popular songs has helped spread terms as they are adopted. In New York itself the unique blend of languages is called Nuyorican. In this form of Spanglish, "New York" becomes Nuevayork, and many Puerto Ricans refer to themselves as Nuevarriqueños. Puerto Rican teenagers are as likely to attend un pahry (a party) as to attend a fiesta; children look forward to a visit from Sahnta Close on Christmas; and workers often have un Beeg Mahk y una Coca-Cola on their lunch breaks.

GREETINGS AND OTHER COMMON EXPRESSIONS

For the most part, Puerto Rican greetings are standard Spanish greetings: Hola ("OH lah")—Hello; ¿Como está? ("como eh-STAH")—How are you?; ¿Que tal? ("kay TAHL")—What's up; Adiós ("ah DYOSE")—Good-bye; Por favór ("pore fah-FORE")—Please; Grácias ("GRAH-syahs")— Thank you; Buena suerte ("BWE-na SWAYR-tay")—Good luck; Feliz Año Nuevo ("feh-LEEZ AHN-yoe NWAY-vo")—Happy New Year.

Some expressions, however, appear to be unique to Puerto Ricans. These include: Mas enamorado que el cabro cupido (More in love than a goat shot by Cupid's arrow; or, to be head over heels in love); Sentado an el baúl (Seated in a trunk; or, to be henpecked); and Sacar el ratón (Let the rat out of the bag; or, to get drunk).

Family and Community Dynamics

Puerto Rican family and community dynamics have a strong Spanish influence and still tend to reflect

Both Puerto Rican men and women care very much for their children and have strong roles in childrearing; children are expected to show respeto (respect) to parents and other elders, including older siblings. Traditionally, girls are raised to be quiet and diffident, and boys are raised to be more aggressive, though all children are expected to defer to elders and strangers. Young men initiate courtship, though dating rituals have for the most part become Americanized on the mainland. Puerto Ricans place a high value on the education of the young; on the island, Americanized public education is compulsory. And like most Latino groups, Puerto Ricans are traditionally opposed to divorce and birth out of wedlock.

Puerto Rican family structure is extensive; it is based on the Spanish system of compadrazco (literally "co-parenting") in which many members—not just parents and siblings—are considered to be part of the immediate family. Thus los abuelos (grandparents), and los tios y las tias (uncles and aunts) and even los primos y las primas (cousins) are considered extremely close relatives in the Puerto Rican family structure. Likewise, los padrinos (godparents) have a special role in the Puerto Rican conception of the family: godparents are friends of a child's parents and serve as "second parents" to the child. Close friends often refer to each other as compadre y comadre to reinforce the familial bond.

Although the extended family remains standard among many Puerto Rican mainlanders and islanders, the family structure has suffered a serious breakdown in recent decades, especially among urban mainlander Puerto Ricans. This breakdown seems to have been precipitated by economic hardships among Puerto Ricans, as well as by the influence of America's social organization, which deemphasizes the extended family and accords greater autonomy to children and women.

For Puerto Ricans, the home has special significance, serving as the focal point for family life. Puerto Rican homes, even in the mainland United States, thus reflect Puerto Rican cultural heritage to a great extent. They tend to be ornate and colorful, with rugs and gilt-framed paintings that often reflect a religious theme. In addition, rosaries, busts of La Virgin (the Virgin Mary) and other religious icons have a prominent place in the household. For many Puerto Rican mothers and grandmothers, no home is complete without a representation of the suffering of Jesús Christo and the Last Supper. As young people increasingly move into mainstream American culture, these traditions and many others seem to be waning, but only slowly over the last few decades.

INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS

Because of the long history of intermarriage among Spanish, Indian, and African ancestry groups, Puerto Ricans are among the most ethnically and racially diverse people in Latin America. As a result, the relations between whites, blacks, and ethnic groups on the island—and to a somewhat lesser extent on the mainland—tend to be cordial.

This is not to say that Puerto Ricans fail to recognize racial variance. On the island of Puerto Rico, skin color ranges from black to fair, and there are many ways of describing a person's color. Light-skinned persons are usually referred to as blanco (white) or rúbio (blond). Those with darker skin who have Native American features are referred to as indio, or "Indian." A person with dark-colored skin, hair, and eyes—like the majority of the islanders—are referred to as trigeño (swarthy). Blacks have two designations: African Puerto Ricans are called people de colór or people "of color," while African Americans are referred to as moreno. The word negro, meaning "black," is quite common among Puerto Ricans, and is used today as a term of endearment for persons of any color.

Religion

Most Puerto Ricans are Roman Catholics. Catholicism on the island dates back to the earliest presence of the Spanish conquistadors, who brought Catholic missionaries to convert native Arawaks to Christianity and train them in Spanish customs and culture. For over 400 years, Catholicism was the island's dominant religion, with a negligible presence of Protestant Christians. That has changed over the last century. As recently as 1960, over 80 percent of Puerto Ricans identified themselves as Catholics. By the mid-1990s, according to U.S. Census Bureau statistics, that number had decreased to 70 percent. Nearly 30 percent of Puerto Ricans identify themselves as Protestants of various denominations, including Lutheran, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, and Christian Scientist. The Protestant shift is about the same among mainlander Puerto Ricans. Although this trend may be attributable to the overwhelming influence of American culture on the island and among mainland Puerto Ricans, similar changes have been observed throughout the Caribbean and into the rest of Latin America.

Puerto Ricans who practice Catholicism observe traditional church liturgy, rituals, and traditions. These include belief in the Creed of the Apostles and adherence to the doctrine of papal infallibility. Puerto Rican Catholics observe the seven Catholic sacraments: Baptism, Eucharist, Confirmation, Penance, Matrimony, Holy Orders, and Anointing of the Sick. According to the dispensations of Vatican II, Puerto Ricans celebrate mass in vernacular Spanish as opposed to ancient Latin. Catholic churches in Puerto Rico are ornate, rich with candles, paintings, and graphic imagery: like other Latin Americans, Puerto Ricans seem especially moved by the Passion of Christ and place particular emphasis on representations of the Crucifixion.

Among Puerto Rican Catholics, a small minority actively practice some version of santería ("sahnteh-REE-ah"), an African American pagan religion with roots in the Yoruba religion of western Africa. (A santo is a saint of the Catholic church who also corresponds to a Yoruban deity.) Santería is prominent throughout the Caribbean and in many places in the southern United States and has had a strong influence on Catholic practices on the island.

Employment and Economic Traditions

Early Puerto Rican migrants to the mainland, especially those settling in New York City, found jobs in service and industry sectors. Among women, garment industry work was the leading form of employment. Men in urban areas most often worked in the service industry, often at restaurant jobs—bussing tables, bartending, or washing dishes. Men also found work in steel manufacturing, auto assembly, shipping, meat packing, and other related industries. In the early years of mainland migration, a sense of ethnic cohesion, especially in New York City, was created by Puerto Rican men who held jobs of community significance: Puerto Rican barbers, grocers, barmen, and others provided focal points for the Puerto Rican community to gather in the city. Since the 1960s, some Puerto Ricans have been journeying to the mainland as temporary contract laborers—working seasonally to harvest crop vegetables in various states and then returning to Puerto Rico after harvest.

As Puerto Ricans have assimilated into mainstream American culture, many of the younger generations have moved away from New York City and other eastern urban areas, taking high-paying white-collar and professional jobs. Still, less than two percent of Puerto Rican families have a median income above $75,000.

In mainland urban areas, though, unemployment is rising among Puerto Ricans. According to 1990 U.S. Census Bureau statistics, 31 percent of all Puerto Rican men and 59 percent of all Puerto Rican women were not considered part of the American labor force. One reason for these alarming statistics may be the changing face of American employment options. The sort of manufacturing sector jobs that were traditionally held by Puerto Ricans, especially in the garment industry, have become increasingly scarce. Institutionalized racism and the rise in single-parent households in urban areas over the last two decades may also be factors in the employment crisis. Urban Puerto Rican unemployment—whatever its cause—has emerged as one of the greatest economic challenges facing Puerto Rican community leaders at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

Politics and Government

Throughout the twentieth century, Puerto Rican political activity has followed two distinct paths— one focusing on accepting the association with the United States and working within the American political system, the other pushing for full Puerto Rican independence, often through radical means. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, most Puerto Rican leaders living in New York City fought for Caribbean freedom from Spain in general and Puerto Rican freedom in particular. When Spain ceded control of Puerto Rico to the United States following the Spanish-American War, those freedom fighters turned to working for Puerto Rican independence from the States. Eugenio María de Hostos founded the League of Patriots to help smooth the transition from U.S. control to independence. Although full independence was never achieved, groups like the League paved the way for Puerto Rico's special relationship with the United States. Still, Puerto Ricans were for the most part blocked from wide participation in the American political system.

In 1913 New York Puerto Ricans helped establish La Prensa, a Spanish-language daily newspaper, and over the next two decades a number of Puerto Rican and Latino political organizations and groups—some more radical than others—began to form. In 1937 Puerto Ricans elected Oscar García Rivera to a New York City Assembly seat, making him New York's first elected official of Puerto Rican decent. There was some Puerto Rican support in New York City of radical activist Albizu Campos, who staged a riot in the Puerto Rican city of Ponce on the issue of independence that same year; 19 were killed in the riot, and Campos's movement died out.

The 1950s saw wide proliferation of community organizations, called ausentes. Over 75 such hometown societies were organized under the umbrella of El Congresso de Pueblo (the "Council of Hometowns"). These organizations provided services for Puerto Ricans and served as a springboard for activity in city politics. In 1959 the first New York City Puerto Rican Day parade was held. Many commentators viewed this as a major cultural and political "coming out" party for the New York Puerto Rican community.

Low participation of Puerto Ricans in electoral politics—in New York and elsewhere in the country—has been a matter of concern for Puerto Rican leaders. This trend is partly attributable to a nationwide decline in American voter turnout. Still, some studies reveal that there is a substantially higher rate of voter participation among Puerto Ricans on the island than on the U.S. mainland. A number of reasons for this have been offered. Some point to the low turnout of other ethnic minorities in U.S. communities. Others suggest that Puerto Ricans have never really been courted by either party in the American system. And still others suggest that the lack of opportunity and education for the migrant population has resulted in widespread political cynicism among Puerto Ricans. The fact remains, however, that the Puerto Rican population can be a major political force when organized.

Individual and Group Contributions

Although Puerto Ricans have only had a major presence on the mainland since the mid-twentieth century, they have made significant contributions to American society. This is especially true in the areas of the arts, literature, and sports. The following is a selected list of individual Puerto Ricans and some of their achievements.

ACADEMIA

Frank Bonilla is a political scientist and a pioneer of Hispanic and Puerto Rican Studies in the United States. He is the director of the City University of New York's Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños and the author of numerous books and monographs. Author and educator Maria Teresa Babín (1910– ) served as director of the University of Puerto Rico's Hispanic Studies Program. She also edited one of only two English anthologies of Puerto Rican literature.

ART

Olga Albizu (1924– ) came to fame as a painter of Stan Getz's RCA record covers in the 1950s. She later became a leading figure in the New York City arts community. Other well-known contemporary and avant-garde visual artists of Puerto Rican descent include Rafael Ferre (1933– ), Rafael Colón (1941– ), and Ralph Ortíz (1934– ).

MUSIC

Ricky Martin, born Enrique Martin Morales in Puerto Rico, began his career as a member of the teen singing group Menudo. He gained international fame at the 1999 Grammy Awards ceremony with his rousing performance of "La Copa de la Vida." His continued success, most notably with his single "La Vida Loca" was a major influence in the growing interest in new Latin beat styles among mainstream America in the late 1990s.

Marc Anthony (born Marco Antonio Muniz) gained renown both as an actor in films like The Substitute (1996), Big Night (1996), and Bringing out the Dead (1999) and as a top selling Salsa song writer and performer. Anthony has contributed hit songs to albums by other singers and recorded his first album, The Night Is Over, in 1991 in Latin hip hop-style. Some of his other albums reflect more of his Salsa roots and include Otra Nota in 1995 and Contra La Corriente in 1996.

BUSINESS

Deborah Aguiar-Veléz (1955– ) was trained as a chemical engineer but became one of the most famous female entrepreneurs in the United States. After working for Exxon and the New Jersey Department of Commerce, Aguiar-Veléz founded Sistema Corp. In 1990 she was named the Outstanding Woman of the Year in Economic Development. John Rodriguez (1958– ) is the founder of AD-One, a Rochester, New York-based advertising and public relations firm whose clients include Eastman Kodak, Bausch and Lomb, and the Girl Scouts of America.

FILM AND THEATER

San Juan-born actor Raúl Juliá (1940-1994), best known for his work in film, was also a highly regarded figure in the theater. Among his many film credits are Kiss of the Spider Woman, based on South American writer Manuel Puig's novel of the same name, Presumed Innocent, and the Addams Family movies. Singer and dance Rita Moreno (1935– ), born Rosita Dolores Alverco in Puerto Rico, began working on Broadway at the age of 13 and hit Hollywood at age 14. She has earned numerous awards for her work in theater, film, and television. Miriam Colón (1945– ) is New York City's first lady of Hispanic theater. She has also worked widely in film and television. José Ferrer (1912– ), one of cinema's most distinguished leading men, earned a 1950 Academy Award for best actor in the film Cyrano de Bergerac.

Jennifer Lopez, born July 24, 1970 in the Bronx, is a dancer, an actress, and a singer, and has gained fame successively in all three areas. She began her career as a dancer in stage musicals and music videos and in the Fox Network TV show In Living Color. After a string of supporting roles in movies such as Mi Familia (1995) and Money Train (1995), Jennifer Lopez became the highest paid Latina actress in films when she was selected for the title role in Selena in 1997. She went on to act in Anaconda (1997), U-turn (1997), Antz (1998) and Out Of Sight (1998). Her first solo album, On the 6, released in 1999, produced a hit single, "If You Had My Love."

LITERATURE AND JOURNALISM

Jesús Colón (1901-1974) was the first journalist and short story writer to receive wide attention in English-language literary circles. Born in the small Puerto Rican town of Cayey, Colón stowed away on a boat to New York City at the age of 16. After working as an unskilled laborer, he began writing newspaper articles and short fiction. Colón eventually became a columnist for the Daily Worker; some of his works were later collected in A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches. Nicholasa Mohr (1935– ) is the only Hispanic American woman to write for major U.S. publishing houses, including Dell, Bantam, and Harper. Her books include Nilda (1973), In Nueva York (1977) and Gone Home (1986). Victor Hernández Cruz (1949– ) is the most widely acclaimed of the Nuyorican poets, a group of Puerto Rican poets whose work focuses on the Latino world in New York City. His collections include Mainland (1973) and Rhythm, Content, and Flavor (1989). Tato Laviena (1950– ), the best-selling Latino poet in the United States, gave a 1980 reading at the White House for U.S. President Jimmy Carter. Geraldo Rivera (1943– ) has won ten Emmy Awards and a Peabody Award for his investigative journalism. Since 1987 this controversial media figure has hosted his own talk show, Geraldo.

POLITICS AND LAW

José Cabrenas (1949– ) was the first Puerto Rican to be named to a federal court on the U.S. mainland. He graduated from Yale Law School in 1965 and received his LL.M. from England's Cambridge University in 1967. Cabrenas held a position in the Carter administration, and his name has since been raised for a possible U.S. Supreme Court nomination. Antonia Novello (1944– ) was the first Hispanic woman to be named U.S. surgeon general. She served in the Bush administration from 1990 until 1993.

SPORTS

Roberto Walker Clemente (1934-1972) was born in Carolina, Puerto Rico, and played center field for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955 until his death in 1972. Clemente appeared in two World Series contests, was a four-time National League batting champion, earned MVP honors for the Pirates in 1966, racked up 12 Gold Glove awards for fielding, and was one of only 16 players in the history of the game to have over 3,000 hits. After his untimely death in a plane crash en route to aid earthquake victims in Central America, the Baseball Hall of Fame waived the usual five-year waiting period and inducted Clemente immediately. Orlando Cepeda (1937– ) was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, but grew up in New York City, where he played sandlot baseball. He joined the New York Giants in 1958 and was named Rookie of the Year. Nine years later he was voted MVP for the St. Louis Cardinals. Angel Thomas Cordero (1942– ), a famous name in the world of horseracing, is the fourth all-time leader in races won—and Number Three in the amount of money won in purses: $109,958,510 as of 1986. Sixto Escobar (1913– ) was the first Puerto Rican boxer to win a world championship, knocking out Tony Matino in 1936. Chi Chi Rodriguez (1935– ) is one of the best-known American golfers in the world. In a classic rags-to-riches story, he started out as a caddie in his hometown of Rio Piedras and went on to become a millionaire player. The winner of numerous national and world tournaments, Rodriguez is also known for his philanthropy, including his establishment of the Chi Chi Rodriguez Youth Foundation in Florida.

Media

More than 500 U.S. newspapers, periodicals, newsletters, and directories are published in Spanish or have a significant focus on Hispanic Americans. More than 325 radio and television stations air broadcasts in Spanish, providing music, entertainment, and information to the Hispanic community.

El Diario/La Prensa.

Published Monday through Friday, since 1913, this publication has focused on general news in Spanish.

Contact: Carlos D. Ramirez, Publisher.

Address: 143-155 Varick Street, New York, New York 10013.

Telephone: (718) 807-4600.

Fax: (212) 807-4617.

Hispanic.

Established in 1988, it covers Hispanic interests and people in a general editorial magazine format on a monthly basis.

Address: 98 San Jacinto Boulevard, Suite 1150, Austin, Texas 78701.

Telephone: (512) 320-1942.

Hispanic Business.

Established in 1979, this is a monthly English-language business magazine that caters to Hispanic professionals.

Contact: Jesus Echevarria, Publisher.

Address: 425 Pine Avenue, Santa Barbara, California 93117-3709.

Telephone: (805) 682-5843.

Fax: (805) 964-5539.

Online: http://www.hispanstar.com/hb/default.asp .

Hispanic Link Weekly Report.

Established in 1983, this is a weekly bilingual community newspaper covering Hispanic interests.

Contact: Felix Perez, Editor.

Address: 1420 N Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005.

Telephone: (202) 234-0280.

Noticias del Mundo.

Established in 1980, this is a daily general Spanish-language newspaper.

Contact: Bo Hi Pak, Editor.

Address: Philip Sanchez Inc., 401 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

Telephone: (212) 684-5656.

Vista.

Established in September 1985, this monthly magazine supplement appears in major daily English-language newspapers.

Contact: Renato Perez, Editor.

Address: 999 Ponce de Leon Boulevard, Suite 600, Coral Gables, Florida 33134.

Telephone: (305) 442-2462.

RADIO

Caballero Radio Network.

Contact: Eduardo Caballero, President.

Address: 261 Madison Avenue, Suite 1800, New York, New York 10016.

Telephone: (212) 697-4120.

CBS Hispanic Radio Network.

Contact: Gerardo Villacres, General Manager.

Address: 51 West 52nd Street, 18th Floor, New York, New York 10019.

Telephone: (212) 975-3005.

Lotus Hispanic Radio Network.

Contact: Richard B. Kraushaar, President.

Address: 50 East 42nd Street, New York, New York 10017.

Telephone: (212) 697-7601.

WHCR-FM (90.3).

Public radio format, operating 18 hours daily with Hispanic news and contemporary programming.

Contact: Frank Allen, Program Director.

Address: City College of New York, 138th and Covenant Avenue, New York, New York 10031.

Telephone: (212) 650-7481.

WKDM-AM (1380).

Independent Hispanic hit radio format with continuous operation.

Contact: Geno Heinemeyer, General Manager.

Address: 570 Seventh Avenue, Suite 1406, New York, New York 10018.

Telephone: (212) 564-1380.

TELEVISION

Galavision.

Hispanic television network.

Contact: Jamie Davila, Division President.

Address: 2121 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 2300, Los Angeles, California 90067.

Telephone: (310) 286-0122.

Telemundo Spanish Television Network.

Contact: Joaquin F. Blaya, President.

Address: 1740 Broadway, 18th Floor, New York, New York 10019-1740.

Telephone: (212) 492-5500.

Univision.

Spanish-language television network, offering news and entertainment programming.

Contact: Joaquin F. Blaya, President.

Address: 605 Third Avenue, 12th Floor, New York, New York 10158-0180.

Telephone: (212) 455-5200.

WCIU-TV, Channel 26.

Commercial television station affiliated with the Univision network.

Contact: Howard Shapiro, Station Manager.

Address: 141 West Jackson Boulevard, Chicago, Illinois 60604.

Telephone: (312) 663-0260.

WNJU-TV, Channel 47.

Commercial television station affiliated with Telemundo.

Contact: Stephen J. Levin, General Manager.

Address: 47 Industrial Avenue, Teterboro, New Jersey 07608.

Telephone: (201) 288-5550.

Organizations and Associations

Association for Puerto Rican-Hispanic Culture.

Founded in 1965. Seeks to expose people of various ethnic backgrounds and nationalities to cultural values of Puerto Ricans and Hispanics. Focuses on music, poetry recitals, theatrical events, and art exhibits.

Contact: Peter Bloch.

Address: 83 Park Terrace West, New York, New York 10034.

Telephone: (212) 942-2338.

Council for Puerto Rico-U.S. Affairs.

Founded in 1987, the council was formed to help create a positive awareness of Puerto Rico in the United States and to forge new links between the mainland and the island.

Contact: Roberto Soto.

Address: 14 East 60th Street, Suite 605, New York, New York 10022.

Telephone: (212) 832-0935.

National Association for Puerto Rican Civil Rights (NAPRCR).

Addresses civil rights issues concerning Puerto Ricans in legislative, labor, police, and legal and housing matters, especially in New York City.

Contact: Damaso Emeric, President.

Address: 2134 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10035.

Telephone: (212) 996-9661.

National Conference of Puerto Rican Women (NACOPRW).

Founded in 1972, the conference promotes the participation of Puerto Rican and other Hispanic women in social, political, and economic affairs in the United States and in Puerto Rico. Publishes the quarterly Ecos Nationales.

Contact: Ana Fontana.

Address: 5 Thomas Circle, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005.

Telephone: (202) 387-4716.

National Council of La Raza.

Founded in 1968, this Pan-Hispanic organization provides assistance to local Hispanic groups, serves as an advocate for all Hispanic Americans, and is a national umbrella organization for 80 formal affiliates throughout the United States.

Address: 810 First Street, N.E., Suite 300, Washington, D.C. 20002.

Telephone: (202) 289-1380.

National Puerto Rican Coalition (NPRC).

Founded in 1977, the NPRC advances the social, economic, and political well-being of Puerto Ricans. It evaluates the potential impact of legislative and government proposals and policies affecting the Puerto Rican community and provides technical assistance and training to start-up Puerto Rican organizations. Publishes National Directory of Puerto Rican Organizations; Bulletin; Annual Report.

Contact: Louis Nuñez, President.

Address: 1700 K Street, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, D.C. 20006.

Telephone: (202) 223-3915.

Fax: (202) 429-2223.

National Puerto Rican Forum (NPRF).

Concerned with the overall improvement of Puerto Rican and Hispanic communities throughout the United States

Contact: Kofi A. Boateng, Executive Director.

Address: 31 East 32nd Street, Fourth Floor, New York, New York 10016-5536.

Telephone: (212) 685-2311.

Fax: (212) 685-2349.

Online: http://www.nprf.org/ .

Puerto Rican Family Institute (PRFI).

Established for the preservation of the health, wellbeing, and integrity of Puerto Rican and Hispanic families in the United States.

Contact: Maria Elena Girone, Executive Director.

Address: 145 West 15th Street, New York, New York 10011.

Telephone: (212) 924-6320.

Fax: (212) 691-5635.

Museums and Research Centers

Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Center for Latino Studies.

Research institute centered on the study of Puerto Ricans in New York and Puerto Rico. Focuses on history, politics, sociology, and anthropology.

Contact: Maria Sanchez.

Address: 1205 Boylen Hall, Bedford Avenue at Avenue H, Brooklyn, New York 11210.

Telephone: (718) 780-5561.

Hunter College of the City University of New York Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños.

Founded in 1973, it is the first university-based research center in New York City designed specifically to develop Puerto Rican perspectives on Puerto Rican problems and issues.

Contact: Juan Flores, Director.

Address: 695 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10021.

Telephone: (212) 772-5689.

Fax: (212) 650-3673.

E-mail: hcordero@shiva.hunter.cuny.edu.

Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, Archivo General de Puerto Rico.

Maintains extensive archival holdings relating to the history of Puerto Rico.

Contact: Carmen Davila.

Address: 500 Ponce de León, Suite 4184, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00905.

Telephone: (787) 725-5137.

Fax: (787) 724-8393.

PRLDEF Institute for Puerto Rican Policy.

The Institute for Puerto Rican Policy merged with the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund in 1999. In September of 1999 a website was in progress but unfinished.

Contact: Angelo Falcón, Director.

Address: 99 Hudson Street, 14th Floor, New York, New York 10013-2815.

Telephone: (212) 219-3360 ext. 246.

Fax: (212) 431-4276.

E-mail: ipr@iprnet.org.

Puerto Rican Culture Institute, Luis Muñoz Rivera Library and Museum.

Founded in 1960, it houses collections that emphasize literature and art; institute supports research into the cultural heritage of Puerto Rico.

Address: 10 Muñoz Rivera Street, Barranquitas, Puerto Rico 00618.

Telephone: (787) 857-0230.

Sources for Additional Study

Alvarez, Maria D. Puerto Rican Children on the Mainland: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. New York: Garland Pub., 1992.

Dietz, James L. Economic History of Puerto Rico: Institutional Change and Capitalist Development. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Falcón, Angelo. Puerto Rican Political Participation: New York City and Puerto Rico. Institute for Puerto Rican Policy, 1980.

Fitzpatrick, Joseph P. Puerto Rican Americans: The Meaning of Migration to the Mainland. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1987.

——. The Stranger Is Our Own: Reflections on the Journey of Puerto Rican Migrants. Kansas City, Missouri: Sheed & Ward, 1996.

Growing up Puerto Rican: An Anthology, edited by Joy L. DeJesus. New York: Morrow, 1997.

Hauberg, Clifford A. Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans. New York: Twayne, 1975.

Perez y Mena, Andres Isidoro. Speaking with the Dead: Development of Afro-Latin Religion Among Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Study into Inter-penetration of Civilizations in the New World. New York: AMS Press, 1991.

Puerto Rico: A Political and Cultural History, edited by Arturo Morales Carrion. New York: Norton, 1984.

Urciuoli, Bonnie. Exposing Prejudice: Puerto Rican Experiences of Language, Race, and Class. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996.

I am a Puerto Rican woman doing the Ph.D. on Clinical Social Work at Smith College, Northampton, MA. The topic of my dissertation is the process of acculturation for Puerto Rican women like myself that came to the USA at an adult age.

Researching the literature, I found that according to Ramos (2005) and Koss-Chioino (1999), Puerto Ricans have a higher prevalence for depression, and Puerto Rican women are more likely than men to suffer from depression. In her article, Ramos (2005) addresses how acculturation can have a serious psychological impact on the individual’s functioning. The reference are as follow:

Ramos, Blanca (2005). Acculturation and Depression among Puerto Ricans in the Mainland. Social Work Research, 29, (2), 95-105.

Koss-Chioino, J.D. (1999). Depression Among Puerto Rican Women: Culture, Etiology and Diagnosis, Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21 (3), 330-350.

I would love to be in contact with women like myself, that I can interview for my dissertation.

Thanks;

Selma

In short I want to tell you the BEST of luck to you, if you are not already done.

Anika

sincerely - La Negra (selmene rodriquez)

It definitely helped me for my college paper that I was having trouble finding information on. I will be using this for other Hispanic groups as I move along in my paper.

Thank you!

There is a list of sources for additional study, but I would like to know what the sources were that directly contributed to this article.

Thanks for the article

Some last names (which I actually know the person or are in my familly are), that are from non spanish origins are: Bochetti, Bracetti, Planell, Farinacci, Vescovacci, Paraliticci, Gigliotti, Capetillo, Carde (Cardi) Santini (Like the mayor of San Juan and the President of Corsica). Other last names Giraud (French), O'neil (Like the mayor of Guaynabo), Irish, Bristol (British), etc. When you come to the island please visit the center, the west and the south, we are also very proud puertoricans. And yes we still have the Spanish, Taino and African in our blood but with other spices.

It has been an amazing experience. Now!! I have some solid information to reference when someone ask me about my Puerto Rican... heritage.

Once again a million thanks..

Angela Negron

I found the information quite accurate for the most part save some regionally influenced elements. One thing the greatly concerns me, however is the urban centric basis by which most information about Puerto Rican Americans are described in virtually all documents. It would be very informative and frankly, helpful if some analysis of those Puerto Ricans (such as myself) which assimilated in non urban areas was done. I find my family and those of others dramatically different from urban based latinos in almost every way. For example, those in outlying areas tend to be more self sufficient and entrepreneurial than urban types. We assimilate quicker and become part of our communities much more readily. I find our value systems have remained consistent with those described here and thus we have maintained those elements that strengthen family values while absorbing into the American main stream. I think there is much to learn by conducting the exercise.

However, I think some respect needs to be paid to Hector Lavoe and Willie Colon in the Music section for their contributions to the salsa explosion in the US.

I make sure to bring them to our island- a place that every stateside rican should @ least visit it once- going around d island is food for our soul- go their as a tourist and you could fall in love with this island like i and family did

Sonya Sotomayor US Supreme Court Justice.

Cayetano Coll Toste Writer and Historian.

Pre politics Luis Muñoz Marin and his wife of first marriage Muna Lee, both Poets.

Celso Barbosa the father of the statehood movement.